Stripe co-founder and CEO Patrick Collison delivers his keynote conference during day three of the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona on February 24, 2016.

Manuel Blondeau | AOP.Press | Corbis | Getty Images

Technology firms from Silicon Valley’s Stripe to U.K.-based GoCardless are all trying to grab a slice of the same $1.9 trillion industry.

Payments, a sector long dominated by cash, has gone digital as a number of start-ups enter the fray looking to make it easier to pay for things online as well as in stores.

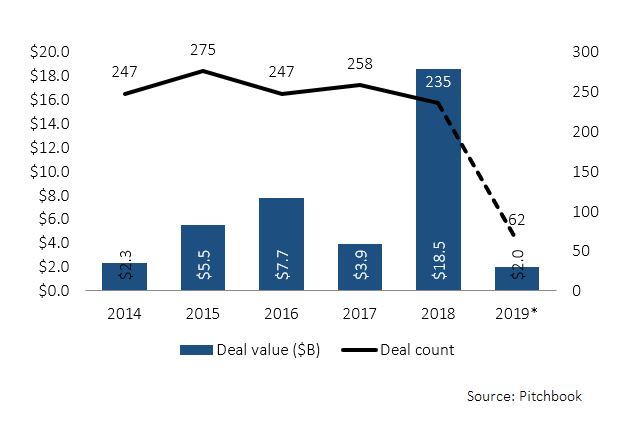

Upstart payment firms have attracted big corporate clients and billions of dollars in venture capital money. According to Pitchbook, investors pumped $18.5 billion into the sector in 2018 — a near-fivefold increase from the previous year.

That was a huge amount of money, but spread over a smaller number of investments, with 235 deals being signed last year compared to 258 in 2017. China’s Ant Financial was the biggest driver of the numbers, Pitchbook says, raising a whopping $14 billion in 2018.

“High level the deal count fell a bit in 2018 but (was) still very healthy and I wouldn’t read anything into that small decline,” said Paul Condra, lead emerging technology analyst at PitchBook.

“Companies that can simplify payments for SMBs (small and medium-sized businesses) or focus on the complexity of cross-border payments have received tremendous attention.”

In the last few months alone, there have been massive deals in the sector:

Pitchbook says the sector has attracted about $2 billion so far into 2019 already.

Not to mention mergers and acquisitions activity in the space. Just last week, CNBC reported that U.S. financial technology firm Global Payments is nearing a deal to buy peer Total System Services for about $20 billion.

Sky-high valuations

Then there’s little-known U.K.-based firm Checkout, which raised $200 million at a $2 billion market value, automatically signing it up to Europe’s unicorn club — unicorns being private tech firms valued at $1 billion or more.

Checkout’s fundraising came as a particular surprise, as the seven-year-old company had previously been entirely owned by its founder and CEO Guillaume Pousaz.

The firm’s boss said the reason it steered clear from the private markets for so long was because it wanted to take a “bootstrap” approach to growing the business — in other words, relying on the resources it had access to — rather than tapping external investment early on.

As for Checkout’s sky-high valuation, Pousaz said: “We would not have achieved the valuation we achieved if we did not grow fast. I think that is the point that has attracted a good valuation, but if anything it reflects the market value.”

Speculation has grown as to whether — or when — one of the payment start-ups will seek an exit strategy, either through an initial public offering or a takeover. Last year saw Adyen debut in Amsterdam, while Sweden’s iZettle was snapped up by PayPal for $2.2 billion ahead of a planned IPO.

With PayPal, it didn’t take long for the 20-year-old fintech firm to launch a public offering, only to then be acquired — and later spun off — by eBay.

But companies appear to be staying private for longer, as plenty of capital flows into start-ups. Meanwhile, Japan’s SoftBank is shaping up the tech investment space with its $100 billion Vision Fund, an investor in an already-listed German payments firm, Wirecard.

While Checkout’s Pousaz didn’t rule out a float, he said it was “too early to speak about an IPO.”

“We are lucky to have investors that have a very long term view,” he said. “We’re never going to discard the IPO, it’s obviously a route towards another liquidity event.”

‘Not revolutionary’

While payment processors like Adyen and Checkout are “not revolutionary,” they execute “extremely well,” said Rob Moffat, a partner at London-based venture capital Balderton Capital.

In essence, Adyen and Checkout are just payment processing companies, but because they have made accepting payments much simpler for merchants, Moffat said, investors have flocked to them.

“I guess we see that continuing,” said Moffat. One area he sees payment processors solving a clear pain point is in direct debit payments, recurring transactions withdrawn directly from customers’ bank accounts.

That’s why Balderton backed GoCardless, which handles what it calls the “recurring payments market.” That means transactions like subscriptions and installments.

Like Checkout’s founder, GoCardless’ co-founder and CEO, Hiroki Takeuchi, has said in the past that he doesn’t see an IPO as an immediate goal for the company, nor does he think of it as an exit.

“For me, an IPO’s not really an exit, it’s just a milestone,” he said in an interview after the firm’s most recent round of funding. “We’ll cross that bridge when we come to it.”

“I’m really focused on how do we create the best possible company which has the biggest possible impact,” Takeuchi added. “Maybe an IPO is part of that journey, but we’ll see when we come to it.”

Stripe, too, has pushed back against the idea of a stock market listing in the immediate term — Chief Operating Officer Claire Hughes Johnson told Fortune magazine last year the firm has “no plans” to do so.

Klarna CEO Sebastian Siemiatkowski, on the other hand, said recently that he actually thinks his company is “where we could seek a stock market listing,” although “it’s unlikely to be this year.”

Signal2forex.com - Best robots Forex sy famantarana

Signal2forex.com - Best robots Forex sy famantarana