Pretty much every single data point emerging from the jobs market these days is signaling that wages should be accelerating — except for actual paychecks.

That looks to be changing soon, even if it’s been a long time coming.

The latest sign came this week, when the Bureau of Labor Statistics said job openings rose to a record 6.6 million positions in March, even if hiring hasn’t been that great lately. Strictly speaking, that should indicate that employers hungry to hire will be forced into paying higher wages to attract workers.

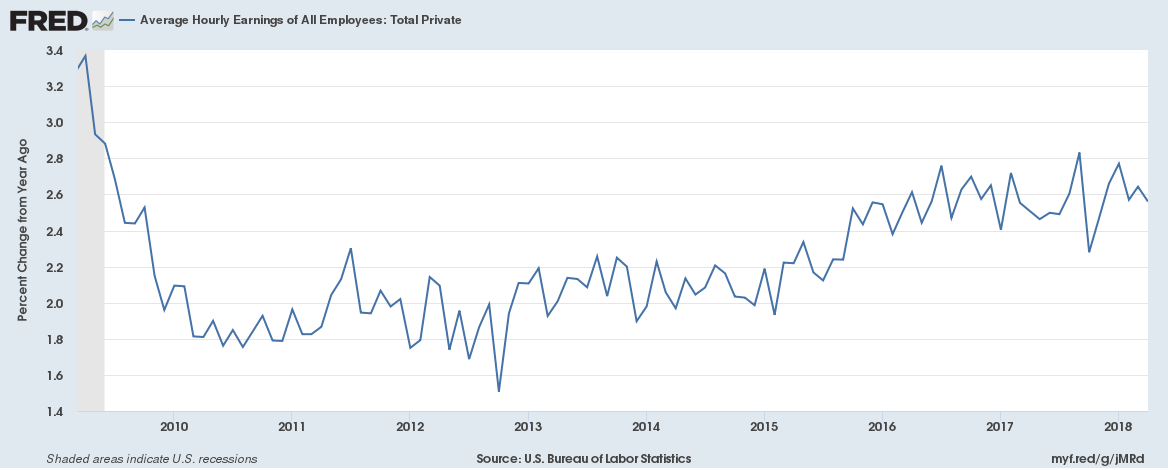

But average hourly earnings growth actually decelerated in April, fueling the continuing conundrum over what’s happening in the labor market.

“All this data signals that wage growth should accelerate going forward,” Nick Colas, co-founder of DataTrek Research, said in his daily market note Wednesday. “Otherwise, the mystery of the missing wage growth will continue.”

Indeed, economists and Federal Reserve policymakers have been in quandary over why wages aren’t higher.

The unemployment rate fell to 3.9 percent in April, but average hourly earnings rose just 2.6 percent over the year, a slowing from the 2.7 percent gain in March.

The last time the unemployment rate was that low, in December 2000, wages grew at a 4.2 percent pace, a level that the job market hasn’t come close to matching throughout the recovery that began in mid-2009.

There are numerous theories for why this hasn’t happened, but the most popular is a skills mismatch that has left employers groping to find workers. In March, there were essentially the same amount of workers that the BLS counted as unemployed as there were job openings.

Multiple surveys that the Fed conducts of its business contacts have indicated that the skills gap remains a major issue.

“If you can’t fill a certain position, by definition you can’t give this nonexistent employee a raise,” Colas wrote. “This dilemma highlights the ongoing difficulty of employers finding qualified workers. The interest is there, but the skills needed to meet many jobs’ requirements are not.”

However, there’s hope.

This week’s Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey indicated a record high in what Colas calls his “take this job and shove it” indicator. That’s a comparison from the JOLTS release between the quits rate, or those leaving their jobs voluntarily, against the total separations, which encompasses all reasons why workers leave or are fired from their positions.

The current level is at 63.2 percent, a record high, which he said “shows a greater belief among workers in their own ability to attain a more lucrative position and that the economy is strong enough to offer better jobs.”

So when does wage inflation finally start showing up?

Any day now, says Amy Glaser, senior vice president at Adecco, the world’s largest staffer of temporary workers.

“It’s truly a candidate’s market, and companies are really struggling to find top talent. So we’re seeing them make concessions,” Glaser said. “Most of my discussions now [with employers] tend to be what is the return on investment they can expect when giving a raise to their employees.”

Companies are offering not only significantly higher wages but also other incentives and benefits to try to lure workers, so long as they can find those with the right qualifications.

Glaser said the current situation “defies the laws of supply and demand,” but economist David Rosenberg said that’s not going to last forever. Rosenberg, chief economist and strategist at Gluskin Sheff, said there’s typically a six-month lag from a peak in quits and a rise in wages, “so we will give it more time.”

“The shape of the curves may be different than they have looked before, but the laws of supply and demand have not been repealed,” Rosenberg wrote in his daily note to clients, adding, “that goes for any market, labor or otherwise.”

Link to the source of information: www.cnbc.com

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals