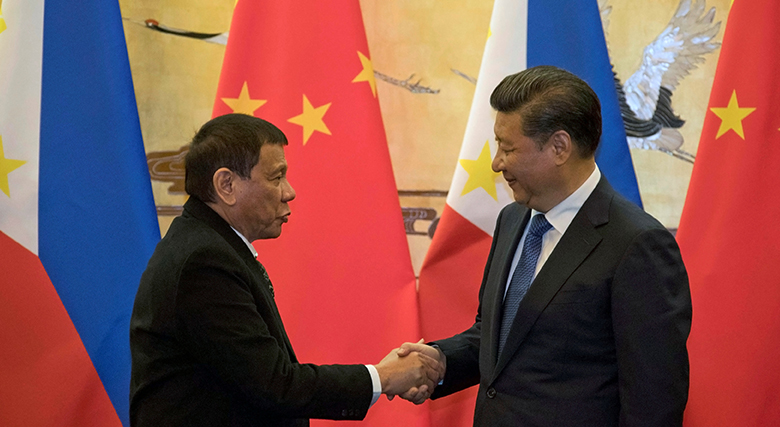

President of the Philippines Rodrigo Duterte (left) with his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping in 2016

When the president of the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte, visited Beijing in October 2016, shook hands with his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping and announced the “separation” of his country from the United States, it felt like a pivotal moment.

For decades after the Second World War, Manila was Washington’s staunchest ally in southeast Asia. Clark Air Base on Luzon island was run by the US Air Force until 1991, and only Japan gave more to the Philippines than the US in terms of aid commitments.

As the new century progressed, Tokyo’s fear of a rising Beijing forced it to commit more resources to the sprawling island chain. It donated patrol boats and financed and built infrastructure. In 2015, the Philippines signed a $2 billion loan agreement with the Japan International Cooperation Agency to fund a high-speed rail link between Manila and the city of Malolos.

Then came China’s coup. Duterte’s visit ruffled feathers not just in Tokyo and Washington, but across the region. When Xi pledged $24 billion in investment, including $9 billion in soft loans and a $3 billion credit line from the Bank of China, many assumed the die was cast. The Philippines, like other states such as Cambodia and Myanmar, would, it seemed, pivot toward Beijing.

But that didn’t happen. So far, the Philippines has signed just one loan agreement with China worth $73 million, to fund an irrigation project north of Manila. Two bridges in the capital, costing a total of $75 million and financed by Beijing, were opened to traffic in July. Yet none of the 27 deals signed between Xi and Duterte, including $15 billion in promised direct investments by mainland firms in domestic energy, port, mining and railway projects, have yet to materialize.

Ernesto Pernia, economic planning secretary, pointed to the lack of progress on China-backed projects in the Philippines as recently as July this year, adding that while financial assistance from Tokyo was speeding up, the process of securing funding from Beijing was “moving slower”.

He also emphasized the divergent cost of capital, noting that while China charges rates of between 2% and 3% on its loans, Japanese development banks and agencies typically impose rates of between 0.25% and 0.75%.

Other fish to fry

Some in Manila believe Beijing is just being slow off the mark with its projects – or that it has other fish to fry. The Belt and Road Initiative, China’s grand plan to redraw the global trade map in its own image, pulls it in many directions, and Beijing’s capital reserves, contrary to appearances, are not limitless.

But others say China was irked when Duterte visited Tokyo to shake hands with Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe, exactly a year after pressing the flesh with Xi. The two leaders toasted a “golden age of strategic partnership”, with Abe pledging $6 billion in fresh investments, to be poured into the construction of new railways, roads, bridges, power plants and transmission lines.

This new funding augments an existing $9 billion aid package. In 2017, loans from Japan amounted to $4.84 billion, or 45% of all official development assistance (ODA) received by the Philippines that year, according to the National Economic and Development Authority.

Our focus is to get projects off the ground as fast as we can. Both countries have made commitments. Japan’s $9 billion is really helpful, but so is the money China is pledging

– Carlos Dominguez, finance secretary, the Philippines

When Asiamoney met the Philippines’ finance secretary Carlos Dominguez in July, it was put to him that Manila might be playing Tokyo and Beijing off against each other, to maximize inward ODA flows and force the two sovereigns to compete over the cost of funding. Dominguez smiles.

“Our focus is to get projects off the ground as fast as we can,” he says. “Both countries have made commitments. Japan’s $9 billion is really helpful, but so is the money China is pledging. We are getting loans at below market value.”

But in a far broader context, Dominguez describes this as a “fight over the soul of Asia” between China and Japan, two countries with vast foreign exchange reserves and powerful export-oriented manufacturing sectors. The coming decades will see the two economic giants duke it out over the right to fund and build vital infrastructure worth trillions of dollars across Asia.

You can see this in the fight to build high-speed rail projects in Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Cambodia and Laos.

Japan wants its bullet trains to whizz between the great cities of southeast Asia; China wants to crash the party and install its own high-speed locomotives.

Criticism

Triumphs and failures are guaranteed. Sometimes both will lose: China and Japan have been criticized for cost overruns and delays on their respective Vietnamese light rail projects in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City.

There is one final piece of the jigsaw. This fight for Asia’s soul is just the latest chapter in a long and shifting history of bilateral rivalry. Usually there are two combatants, but this time, is there a third?

In June this year, Korea offered $1 billion in ODA to the Philippines, promising to build new roads and bridges.

“That’s double what they gave the last administration, and the Koreans build very good infrastructure,” says Dominguez. “Don’t count them out.”

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals