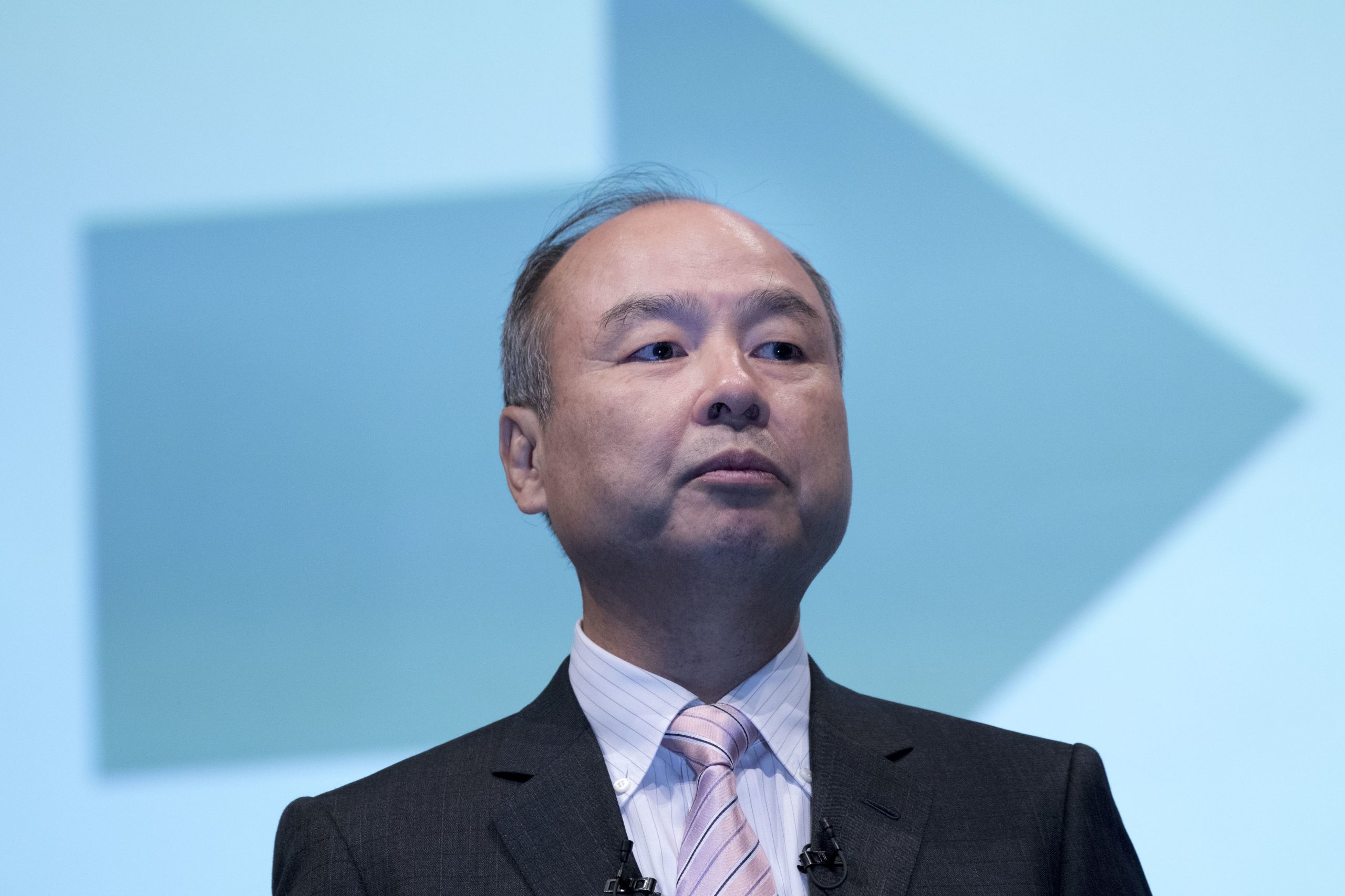

There are two schools of thought on 61-year-old SoftBank founder Masayoshi Son. To quote from the 1990s animated cartoon theme song for “Pinky and the Brain”: One is a genius, the other’s insane.

Son is one of the world’s wealthiest men, with a net worth of more than $20 billion. He founded a Japanese wireless company called SoftBank and invested $20 million in Alibaba in 2000. That investment, plus several later ones in the Chinese e-commerce company, gave SoftBank about a 30% stake in Alibaba, a company with a $440 billion market capitalization. That one investment accounts for much of Son’s wealth. SoftBank’s market capitalization today is $98 billion. The stake in Alibaba is worth more than the entire company.

Son’s SoftBank has a famed 300-year plan, the core philosophies of which theoretically drive the investments behind his $100 billion Vision Fund. Slides from a Son presentation on that 300-year plan include focusing on cloning, 200-year-old human beings and telepathy.

The Vision Fund, which thus far has invested about $80 billion in a startups including Uber, Didi Chuxing, DoorDash, Fanatics, Flexport, Grab, Lemonade, Opendoor, SoFi, and The We Company (WeWork), is crafted after Son’s “vision,” hence the name.

Here’s a paragraph from SoftBank’s website, again alluding to that 300-year plan.

SoftBank aims “to continue to grow as a corporate group for the next 300 years. The SoftBank Group strives to develop over the long-term by forming partnerships with the most superior companies at the time in the information industry, without adhering to particular technologies or business models.”

I’m going to take a quick timeout. A 300-year plan is completely bonkers. It’s asking someone from the year 1719 to predict today, in 30-year increments. It’s a fun exercise. It’s also ridiculous. Put me down for “insane” for this one.

Real life is what SoftBank Vision Fund managing partner Jeff Housenbold told my colleague Riley de Leon.

“I’m not worried about an exit in two to three years,” Housenbold said. “I’m worried about maximizing returns over 7 to 10 to 15 years.”

SoftBank has largely transitioned from a Japanese wireless provider to a diverse investment vehicle, and its investments need to monetize so that investors keep giving Son and SoftBank more money. And while the Vision Fund is still in its relative infancy, its first big investment went public last week — Uber — and there were some problems. Morgan Stanley tried desperately to get investors to value Uber at a higher valuation than its last private round ($76 billion), but the appetite simply wasn’t there. It’s so far never traded above its debut price of $45, and closed its first full week on the market at $41.70.

The New York Times reports that investors’ appetite was suppressed in part by the success of ride-hailing competitors around the world, like Didi in China and 99 in Latin America (now owned by Didi), both of which have received huge funding rounds from…SoftBank. Uber’s fastest-growing segment, the food delivery business Uber Eats, faces stiff competition from venture-backed DoorDash, which has also received a major investment from — you guessed it —SoftBank.

That’s not to say Uber will be a bad investment for SoftBank, which originally bought in at around $33 per share, giving Son a 27% paper gain over Friday’s closing price. Of course, SoftBank also bought in at about $48 per share, so its average blended investment is closer to $36 per share.

SoftBank also owns more than 80% of Sprint. Son is holding out hope that regulators will allow Sprint will to merge with T-Mobile. Otherwise, Sprint may be in jeopardy of losing its entire equity value.

SoftBank has invested $10.5 billion in WeWork, which is preparing for an IPO this year but also said this week it had lost $264 million in the first three months of the year. WeWork also announced a separate fund to invest $2.9 billion into buildings which it will then rent, in part, to itself.

Founders that have taken Vision Fund money are quick to highlight Son’s awesomeness.

“He remembers everything,” Brain Corp. co-founder and CEO Eugene Izhikevich told me last year. “Honestly I’m afraid to talk any numbers with him because six months later he’s quoting them back to people as if we just spoke hours ago. He remembers how much we charge our customers. It’s extraordinary. I wonder, is he like this with every company?”

“SoftBank thinks longer term and bigger,” Brandless Co-founder and CEO Tina Sharkey wrote in a Medium post after accepting Vision Fund money as part of a $240 million funding round for her online retailing company.

“Humbled to have Masayoshi Son from @Softbank place his faith on @Cohesity,” Cohesity founder Mohit Aron tweeted last year after a $250 million funding round led by The Vision Fund.

“Masa has a tremendous vision,” Kabbage co-founder and CEO Rob Frohwein told CNBC.

But what exactly is Son’s vision? Occam’s razor suggests there’s no grand plan — no 300-year purpose — and there shouldn’t be. The Vision Fund’s investments are case-specific. In ride-hailing, perhaps it’s investing in competitors and trying to merge them together and split up markets to gain efficiencies and pricing power. With Sprint, it’s clearly merging with T-Mobile. With WeWork, it’s…something else.

For standard VC investing, that’s fine! That’s the business. You only need a couple of hits to make up for the misses. Alibaba pays for everything else. Hell, Son almost invested in Amazon early too! You have to play to win.

But with late-stage VC investing, the math is trickier. The returns will generally be lower. You’ll need more hits. That’s what will make The Vision Fund’s success, or lack thereof, so interesting to watch in years to come.

Is Son a genius or insane? Maybe he’s just a really ambitious guy with a passion for taking business risks.

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals