When Goldman Sachs asked Hank Paulson to be its man in charge of Asia in 1990, it was for a simple reason: he was based in Chicago, which meant he was slightly closer to the region than his investment banking co-heads in New York – “That will tell you how important Asia was to the firm’s plans back then,” he later recalled.

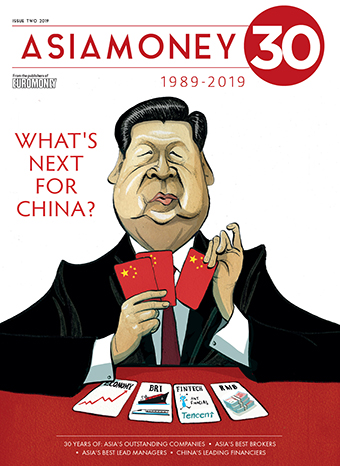

How times have changed. Global banks now have large operations in Hong Kong, Singapore and elsewhere in the region. Asia has become the obvious move for US investment banks eyeing juicy fees, for beleaguered European banks trying to escape tepid growth at home and for private equity firms in search of the next big deal. But while all of Asia has risen in importance, China is clearly in a league of its own.

Asiamoney was first published in October 1989. At the time, China had neither stock exchanges nor well-defined policy banks. Deng Xiaoping, the country’s great market reformer, was struggling to consolidate his power. WTO membership was more than a decade away.

China appears to have evolved little in terms of its political structures since then, but many other things have changed a great deal. The country’s gross domestic product per capita was $310.8 when we first published; it was $8,826.9 at the end of 2017. Chinese banks are now the largest in the world by assets. Chinese companies such as Alibaba and Tencent are famous outside their home markets.

There have also been seismic changes in the way Chinese policymakers treat capital markets. In the late 1990s, when the first Chinese state-owned companies turned to Hong Kong with initial public offerings, offshore firms offered knowledge as much as they did capital. Chinese companies were expected to learn about disclosure standards, business strategy and optimal capital structures.

When foreign firms went in the other direction, they were allowed to make money in China, but they had to share their know-how.

Many of the key lessons have now been learned. With the Bond Connect and Stock Connect schemes, foreign investors have easy access to China’s capital markets. After a raft of rule changes in 2018, foreigners have much greater access to China’s banking, insurance, securities trading and credit ratings.

It is not unusual to hear bankers working at smaller houses talk very generally about how their firm is ‘doing China’. That’s a senseless approach for such a large and varied country

China, long the patient student, has become the teacher. This can occasionally lead to questionable results – debt bankers, in particular, complain about slipping standards – but the priority for global banks is now learning about China, not the other way around. The country remains a puzzle that banks are struggling to crack.

Note: our programmers have developed a profitable forex robot with low risk and stable profit!

How should banks navigate China? The worst approach is to treat it as a monolith. It is not unusual to hear bankers working at smaller houses talk very generally about how their firm is ‘doing China’. That’s a senseless approach for such a large and varied country: the starting point should be identifying the regions or sectors you want to focus on, and from there picking the client base.

The same argument applies to the mix of domestic and international deal flow a bank attempts to capture. It is tempting for banks to try to be the best in Chinese bonds, for example, but that means two different things: are you talking about the offshore or onshore markets? Huge banks might be able to ignore this distinction, but most should pick a side.

There is also, of course, a risk of concentrating too much. Those banks that dedicated themselves to Chinese outbound M&A a few years ago are now wondering how to boost revenues. Those relying on high-yield flows to bolster their fee income now may be thinking the same thing in a few more years.

There are no easy answers. But equally clear are the rewards on offer for those banks that can negotiate China in the coming decades.

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals