Investors in additional tier-one (AT1) debt have certainly learned to be resilient. Not only are they subject to periodic meltdowns in their asset class, but they have had to grapple with the shifting sands of regulation more than most.

This year has been no exception, with a raft of tweaks including a new iteration of the European Union’s Capital Requirements Regulation, dubbed CRR II, which has also given rise to the Single Resolution Board’s own set of updates, published in late June.

One stipulation of the SRB’s update is that banks must now seek approval from the SRB to call AT1 debt, including any with a maturity of less than one year.

The move has prompted some suggestions that extension risk for AT1 debt might increase. It’s a topical point because this has already been on the minds of AT1 market participants in recent months as the asset class moves into a more mature, refinancing stage.

After five years of issuance, last year saw AT1 bonds begin to reach their first call dates. And bank issuers duly stuck to the tradition of calling at the first opportunity – until February 2019. That was when Santander became the first bank to announce it would not call an AT1 bond, a €1.5 billion 6.25% euro-denominated issue whose first call date was in March.

It notified investors at almost the last possible moment. But adding to market confusion was the fact that Santander announced its decision shortly after wrapping up a new dollar AT1 issue that some observers had assumed was intended to refinance the outstanding euro-denominated bond.

Irrational rationale?

The situation left some investors frustrated, even though the bank had previously made it clear to the market that it would approach the matter of calls with a view to the economic rationale in each case.

But that raised another question to make analysts scratch their heads: if economic rationale was to be the guiding principle, how to explain the issuance of the new 7.5% dollar deal which subsequently appeared to have been designed to refinance a 6.375% dollar perpetual that the bank went on to call in May?

After all, one observer estimates that if Santander had opted to refinance the euro issue in February, it might have paid merely an extra 60 basis points, based on the bank’s curve at the time.

For all the initial indignation, however, the market largely took Santander’s move in its stride, and analysts note that investors are beginning to move away from a blanket assumption of calls – even though no other borrower has so far copied Santander’s move.

“Investors understand that this is a more nuanced decision for issuers now,” Pauline Lambert at Scope Ratings tells Euromoney. “They know that there are some banks that will weigh the economic cost more and that there are others for whom it is more important to maintain good relationships with investors.”

That also means that there is likely to be more focus on post-call coupon resets – otherwise known as the back-end coupon – than in the past, and therefore a greater distinction in the minds of investors between bonds with low or high resets.

Larissa Knepper, CreditSights

Although a recent research note from Lambert raised the possibility of elevated risk around calls given the need to seek approval from an extra regulator, in practical terms the additional procedure is unlikely to impact the result – particularly since for the SRB to get involved with an institution in any meaningful way probably requires the ECB to have already deemed that bank to be non-viable, as illustrated by the Banco Popular resolution process in 2017.

“The need to get SRB approval alongside the ECB and your national regulator is a bit academic, as they are unlikely to reach different conclusions,” says Larissa Knepper, an analyst at CreditSights. “All it really does is add to the paperwork.”

That itself can cause hiccups, though. There have been instances in the past of banks being unable to call old-style tier-one bonds even when they wanted to, because of administrative delays to regulatory authorization.

But if anything, conditions are now likely to shift more in favour of calling, given rising expectations of a rate cut in the US and continued loose policy in Europe. And many AT1s, like the bond that Santander did not call in February, have quarterly calls, meaning that banks can take an opportunistic approach.

In the meantime, though, leaving a bond in the market is not without other consequences. Paper deemed likely to be called at any time is unlikely to trade much above par, which can have a dampening effect on the rest of the borrower’s curve.

Coupons, too

Extension risk is only one part of the story. Deutsche Bank AT1 bonds have been under pressure for years as investors fretted over the firm’s capacity or willingness to make coupon payments – worries over its ability to do so were the main trigger for the severe dislocation in the AT1 market in early 2016.

Unsurprisingly, given continued questions over Deutsche Bank’s strategy after announcing its latest reorganization, and despite reassurances by senior executives that the bank intends to continue making AT1 coupon payments, investors appear nervous.

One source of pressure has at least been lifted. A package of amendments to the CRR has helped German banks, whose available distributable items (ADIs) were previously governed by German accounting rules, which are more limiting than regimes like IFRS.

At the end of 2018, Deutsche’s ADIs stood at about €921 million, well above AT1 coupon payments of about €330 million but not far enough above to give investors complete comfort.

The harmonizing change to the CRR means that German banks will now be able to include their capital reserves in the scope of ADI, meaning a boost of about €42 billion for Deutsche Bank and effectively removing ADI as much of a concern.

It can also change how a bank views the instrument. Commerzbank, which had never before issued an AT1, sold a $1 billion 7% AT1 at the start of July that it would have been unable to do easily without the change, which took its ADIs from about €1.2 billion to more than €20 billion.

But it doesn’t mean banks can rest easy: all the change does is shift the focus even further to an institution’s maximum distributable amount (MDA). This is a calculation that banks must perform if their capital ratio is below the additional buffer required by regulators on top of their minimum requirements. The MDA determines what capacity a bank has in those circumstances to make discretionary interest payments.

“ADI measures absolute distribution capacity, but people look more at the MDA, which is relative to capital requirements,” says Knepper at CreditSights.

At the moment, Deutsche Bank’s MDA headroom looks manageable. The bank’s CET1 level was 13.73% in the first quarter of 2019, and the bank has said that it will fall to a minimum of 12.5% under its new restructuring plan. Its MDA threshold is 11.99% on a fully loaded 2019 basis.

Investors seem less comfortable: Knepper notes that at current levels, Deutsche’s $1.25 billion 6.25% notes that will be callable in April 2020 are pricing in not only extension risk but also at least one coupon-skip. Paradoxically, a decision not to call could end up sparking a mini-rally – as was seen on Santander’s paper, with the removal of uncertainty and the recognition by investors of a new approach.

And when it comes to those MDA headrooms, there is also change ahead. At the end of 2020 a new MDA will come into effect, based on the SRB’s minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL) regime.

As a new research note from Scope Ratings highlights (“Evaluating AT1 securities becomes more complex”), AT1 investors will have a tougher job monitoring the extent to which issuers can service their debt.

“This is evolving to the point where investors will need to evaluate whether a bank is meeting various solvency requirements such as leverage and MREL, and not just CET1 capital,” says the note.

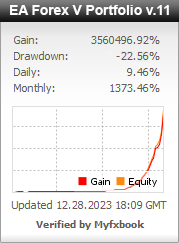

NOTE: Do you want to trade at forex professionally? trade with the help of our forex robots developed by our programmers.

Signal2forex reviews

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals