Tom Montag is a man on a mission. The chief operating officer of Bank of America wants investors to understand that the firm’s global banking and markets business has a unique opportunity within its peer group owing to its local scale coupled with its global footprint.

It’s a combination that Montag reckons has played out in BofA’s performance in the first half of 2019 – and should only get more evident in the years to come.

Montag was giving investors this message at Barclays’ annual three-day financial services conference in New York this week. Speaking in the tiring 3:30pm slot on Monday, the first day of the event, Montag told his audience that he felt like he was in the fifth set of the previous day’s US Open tennis final between Rafael Nadal and Daniil Medvedev, “which was awesome, by the way”.

The synergies across the firm’s eight business lines were becoming more apparent every day, said Montag, but his focus was on BofA’s global banking and markets business – which benefited from being housed at a firm that was one of the few to have a global platform to move, store, trade and lend money in practically all markets around the world.

Remarkably, the fee pool at the five biggest corporate and investment banks has been within a range of $102-$107 billion in every one of the past five years, and BofA reflects this in part. Its first-half global banking unit revenues rose 16% from the first half of 2015 to the first half of 2017, but they have been flat since. Net income, however, is up 48%, and the business has got more efficient, with return on allocated capital rising from 15% to 19%.

And Montag was able to point to recent good performance even in a difficult environment: investment banking revenues fell 3% in the first half of this year, but the industry was down 13%.

And while he predicted that Wall Street’s investment banking revenues would again fall in the current quarter, he said that BofA expected to post a low single-digit year-on-year increase for the period.

He was in no doubt about the main reasons for improved performance in global corporate and investment banking (GCIB).

“Why? One, we’ve changed a number of leaders in that group, so we put Matthew Koder in charge of GCIB. We have two new people in capital markets, Elif Bilgi and Sarang Gadkari, and we’ve just got a new intensity about ourselves and what we’re doing, and that’s allowed us quite frankly to ramp it up.”

Such comments will doubtless be irksome to those who were until recently running those businesses ‒ like Christian Meissner, who was the head of GCIB until he left the bank at the end of 2018, or AJ Murphy, who ran capital markets until she left in early 2019 ‒ particularly as much of the building of BofA’s platform took place on their watch.

Loan and lease growth – standing at 22% since the first half of 2015 – has slowed a little in the current quarter, but Montag was unsurprised by that. He noted that the previous week had seen the biggest number of bond issues ever in the US investment grade market, at 55. And right now issuers were tending to spend more of that money on reducing bank debt than they were on buying back stock. On top of that, an uncertain environment was dampening down the utilization rate of revolvers by small businesses, he said.

Regulatory pressure is ever-present. Montag, joking that the constant battle to manage the firm’s Sifi buffer was akin to weight control, pointed to the many factors that feed into the buffer, including a firm’s stock price, which is outside its control.

Added to that was a potential impact from the move away from Libor, to other alternative rates, such as Sofr, because of the impact of notional swaps on a bank’s Sifi buffer.

“We worry that if Libor goes away and Sofr becomes the instrument of choice, that there will be a large increase in Sofr trading and volumes because people will have to do that because there aren’t term rates – which is fine, we’re supportive of Sofr on that basis, but it just means a lot more notional of swaps, and one of the things that drives the Sifi buffer is swap notional amount.”

Mid-market focus

If anyone still doubted that BofA’s corporate and investment banking strategy right now was focused on the mid-market, Montag’s comments would have put them straight.

The mid-market, defined at BofA as companies with annual revenues of between $50 million and $2 billion, are banked within its global commercial banking (GCB) unit. Those larger sit within global corporate and investment banking.

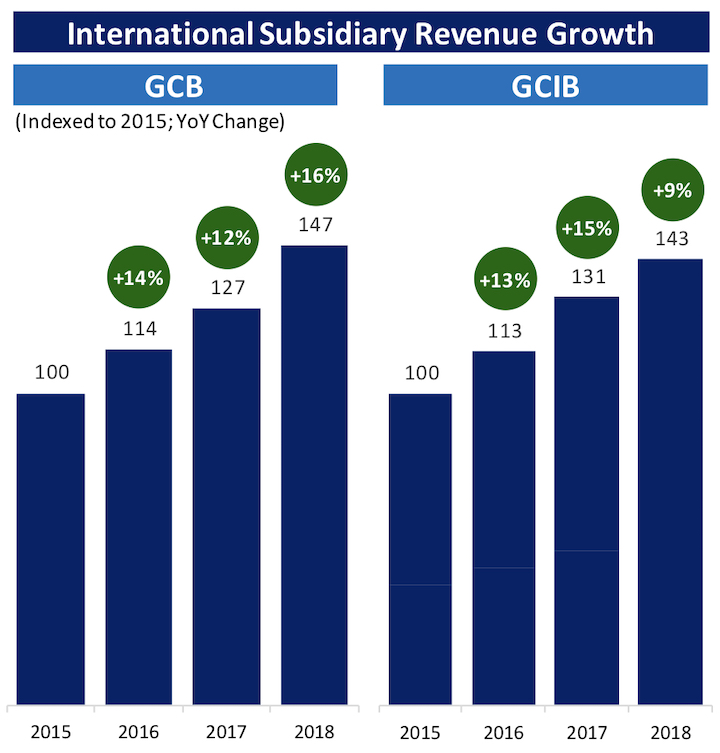

In recent years the bank has been aiming to ramp up its coverage of international subsidiaries of corporate clients, and growth of these in the mid-market has actually outpaced growth at larger clients since 2015. International subsidiary coverage is up 47% within GCB, and 43% in GCIB. As Montag notes, the GCB rise is off a smaller base, but he saw the result as an illustration of how the strategy can pay off with the client set below the very biggest.

| Source: Bank of America |

And the case for the business having more potential looks sound. So far, BofA only banks the international subsidiaries of about one quarter of its mid-market clients in the US, although that is up from about 18% a couple of years ago. “That is only going to go up,” notes Montag, given the bank’s presence in markets like China and India.

Maybe, but in any case the bigger story at BofA, according to Montag, was its US business. Taken together, the commercial banking unit and the business banking unit (clients with revenues of $5 million to $50 million) have added about 600 new relationship bankers since 2014.

About 3,000 net new clients have entered business banking, and about 1,000 in commercial banking. Commercial bankers have been introduced into 49 new locations in the US, and added to 97 others. Investment bankers targeted at the mid-market are now in 18 cities, with Salt Lake and Nashville added in 2019. Three years ago there were none in regional offices.

“What happens when you do this? You call clients more, you see them more, you know them better,” said Montag.

The translation into the financials is startling: US mid-market investment banking revenues (in other words, from GCB clients) are up 17% to end-July year-on-year. Within that, equity capital markets is up 21% and M&A up 56%. Montag cited Dealogic statistics showing that the bank ranks third in North America mid-market M&A, compared to fourth a year ago. “We want to be number one,” he added.

How has that M&A performance in particular been achieved? A big part of the answer is a change in the scope of what the bank allows itself to get involved in.

“We thought about why we were not as good as what we should be,” said Montag, “and one reason was that we were cutting off what M&A we should do and working with outsiders to execute instead of doing it ourselves.” And so the bank decided to lower the size of clients that it would work with.

It’s not just about size, though. The bank also realized that there were other dangers to its previous approach. “A lot of those clients were private clients that we had in global wealth and investment management,” said Montag. “We didn’t want to introduce them to someone else.” After the change in the client-size threshold, so far this year there has been a 67% increase in referrals from wealth management.

The new approach also has more specific impacts, for example in the sponsor business. Previously the bank was focused on the 100 top sponsors in the US, but with its broader client set it can target the top 400. “And strategics want to see those clients too,” he added.

And on top of everything else, the bank has also built a private-side team within its M&A franchise, Montag noted. It is now 17-strong and will have about 30 staff by the middle of 2020.

Low volatility

Montag was similarly upbeat on BofA’s fixed income and equities markets businesses, although here the picture was more mixed.

“The good news is that we are gaining share, the bad news is that fee pools continue to shrink,” he said. In the current quarter equities had done well, while FICC had fallen a little. So far this year the bank had suffered no trading day losses, although “we got close a couple of times”.

Overall sales and trading revenues were down 5% in the last five years, but the industry was down 20% over that period. Montag regularly heard the question asking whether it was possible for a markets business to ever make money now, but he thought it was possible. The bank reckoned it had gained about 1% market share since 2015, he said, but more importantly it considered itself to have the lowest volatility of revenues in its peer group.

He cited BofA’s standard deviation of quarterly year-on-year change in sales and trading revenues of 11% since the start of 2014, while US global systemically important banks (GSIB) averaged 17%. And while the bank was increasing its trading-related assets (up 16% in the second quarter of 2019 versus second quarter 2015), it still ranked only fourth among peers, at $553 billion compared to JPMorgan’s $922 billion.

| Source: Bank of America |

He was trying to tackle patches of weakness too. The bank was number one in the municipal bond market, he said, second in mortgages and securitization and third in corporate credit, but worse in macro and rates, where he saw the biggest potential upside.

Foreign exchange was improving: work in the global transaction services unit as well as international growth more broadly had helped to drive a 74% increase in FX payments volumes over the last five years.

A new delivery mechanism for research would improve the value of its offering there, Montag said, and the bank’s commitment to research had never wavered in spite of the introduction of Mifid II. Institutional Investor ‒ part of the Euromoney group ‒ had recently published its first credit research rankings, with BofA ranked top, he added.

Bigger data

The not-so-secret weapon at a firm like Bank of America is its payments business – the suddenly exciting operation at any bank that has it. Revenues at BofA’s global transaction services unit are up 44% in the last five years, and its international revenues are up 67%. International to international flows – so excluding the US business – are up 17% this year.

One of the reasons why Montag likes transaction services so much – as well as the stickiness of its revenues and the way in which it embeds the bank in a client’s operations – is its data. Until recently, the bank was behind in this area, he readily admits, but that is changing.

“We are starting to use the data. We move about $350 trillion a year, and there’s a lot of data value in $350 trillion of payments,” he said.

Some of that data will be used to add more functionality to the bank’s CashPro platform, which is how it delivers transaction services business to its clients.

But it also all feeds into a new team within the bank, the data innovation group. At the moment the focus for the roughly 30 people who are working on this project is simply sifting through all the data the bank has. That means crunching the 30 million trades it executes each day, the 25 trillion daily risk calculations it makes, the information from its 497,000 CashPro Online users, its 750,000 credit facilities, its 156 million daily equities order and trade messages, its two billion eFX quotes – the list goes on.

A project called Insight Mobile is one way in which some of this will be used for the direct benefit of clients. Montag describes it as a “workstation in your pocket”. If you are a trader, it will tell you your risk in real time and what trades have taken place in your book. It might show you flows that it thinks you will be interested in, or what has happened with orders you are executing through the bank, or allocations that you might have received.

At the moment the gizmo has been rolled out internally, but a client version is in the works.

“Amazon can tell you what shoes you are interested in and what size you wear, but we should be able to do something much more sophisticated than that,” said Montag.

NOTE: Do you want to trade at forex professionally? trade with the help of our forex robot developed by our programmers.

Signal2forex reviews

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals