Euromoney has delved deep into the detail of just how the EU might conduct the large new borrowing programme for the €100 billion emergency SURE programme and the €750 billion recovery fund that was agreed in July.

This programme was hailed as a breakthrough for joint sovereign issuance, with more heavily indebted and vulnerable nations receiving grants as well as loans at a cost subsidized by the credit strength of their wealthier neighbours.

But even if the EU funds this deftly on behalf of the European Commission, there is a much bigger and more important question.

Will it do any good?

Now, €850 billion is a respectable sounding sum of money. But as a one-off boost, it’s only around 6% of EU GDP for 2019. And while economies are tanking now, the recovery fund won’t even come into operation before next year. Recipient countries will be unlikely to receive grants and loans before 2022 or 2023.

How much confidence should investors in those countries’ stand-alone bonds, as well as in broader European equities, take from a temporary arrangement of modest size and delayed implementation?

They should probably take quite a lot.

Common effort

This money will not be sprayed around the whole EU. It will mostly go to its most debt-constrained countries – Greece, Portugal, Spain and Italy – which are also the ones most dependent on the tourism that has been so badly hit by travel restrictions.

Morgan Stanley calculates total grants and loans that might be allocated to Greece at over 25% of GDP; to Portugal at over 15%; to Spain at over 12%; and to Italy at around 9%. And these allocations will come on stream just as the various national fiscal measures to boost economies, announced as lockdowns gripped Europe, taper off.

This common European effort removes questions over those countries’ debt sustainability, at least for now.

Much, of course, depends on whether the money is well spent.

What has been presented as a one-off experiment with a shared budgetary instrument that complements national fiscal actions might well become something far more ambitious and long-standing

The design of the recovery fund, which will approve national projects though qualified majority voting rather than requiring unanimous consent, is geared to investment in green and digital infrastructure – which implies a wait for longer-term returns.

While financing immediate public expenditure would give economies a quicker jolt, investment that boosts demand, growth and productivity might be just what these countries need.

The biggest question is whether the recovery fund is a grand but short-lived gesture of mutual support, or a momentous step towards greater political and fiscal cohesion in Europe?

Tax raising powers

Overlooked amid discussion of all the new liabilities the EU must sell: it has new tax raising powers from which to service these. The first step towards common EU taxation is a modest one on plastic waste. But member states now have the incentive to approve further green and digital tax raising powers to avoid EU debt service costs hitting their own budgets.

What has been presented as a one-off experiment with a shared budgetary instrument that complements national fiscal actions might well become something far more ambitious and long-standing.

And, as discussed, if financing this brings in EU T-bills as a widely accepted risk-free instrument for the whole EU area, it might underpin a genuine capital markets union.

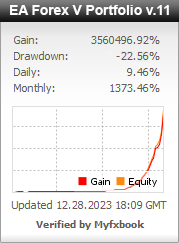

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals