Mike Fredrich shows off unmanned presses in his Manitowoc, Wisconsin, company. They’re ready to start production at MCM Composites, a 55-person enterprise that makes custom thermoset molding.

The only problem? Fredrich has no one to operate them.

“These tools are heated to 300 degrees,” he said. “But we’re not running them. Had we had the people for the first shift, we could have been running this all day. But we don’t, so they sit here heated, ready to go, with no action.”

Fredrich said the business has gone to extremes to try to find the 15 additional employees it needs. But he’s had little success.

“There are no workers, but there’s a huge demand. The economy has picked up, but the market is so thin, that we just can’t find them. We’ve gone to extraordinary means to find people that will actually work, including going to the local county jail and recruiting people to work from inside the jail,” Fredrich said.

Despite record-high confidence on Main Street, a labor shortage issue is increasingly weighing on small businesses like Fredrich’s around the country, proving that a strong economy can cut both ways for businesses.

In fact, according to the National Federation of Independent Businesses’ monthly read on sentiment, labor quality is the number one issue for companies for five months in a row, outpacing taxes and government regulations and red tape. In May, one-third of small-business owners reported job openings they could not fill, and 12 percent reported using temporary workers.

“Finding the right person for the job is always a challenge, but obviously in a tighter market like this, it becomes far more difficult,” said Raymond Keating, chief economist at the nonpartisan Small Business & Entrepreneurship Council. “It’s a function of a few things — the labor participation rate is fairly low for an economic recovery expansion period. So there’s room for people to come back into the labor force. And, as long as economic growth continues, which we want to happen, we are going to have to deal with some tight labor markets.”

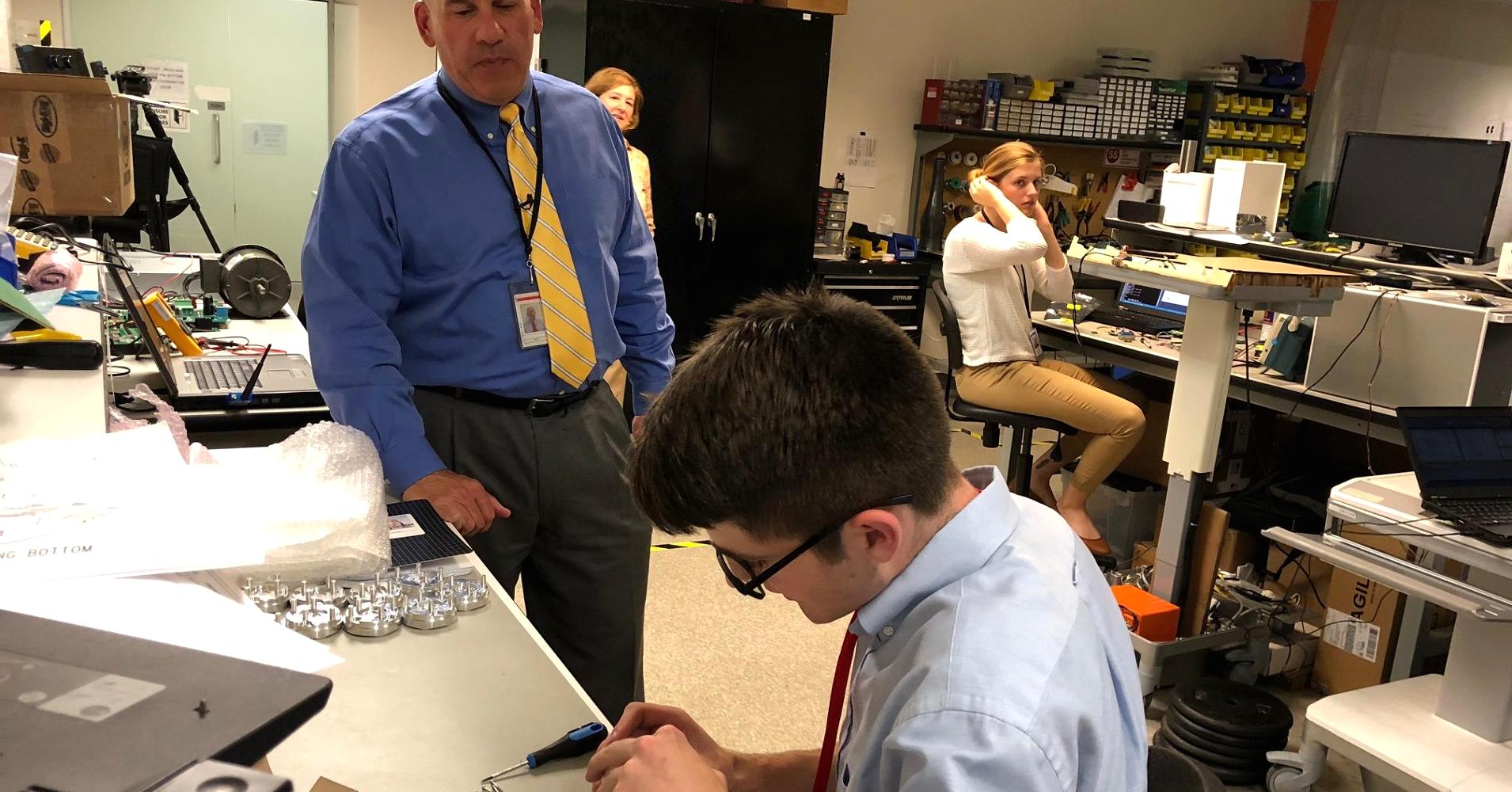

The crunch is being felt across industries and worker skills. Bob Treiber, president of Boston Engineering, a 65-person consultant group in Massachusetts, has 12 open positions for engineers and project managers. But competing with larger businesses for qualified applicants has proved challenging.

“I think it’s easier for larger businesses to make a bigger splash — it’s easier for them to get attention from new hires,” Treiber said.

If he can’t find the right people, the company’s bottom line will suffer.

“If we can’t staff the jobs, we can’t satisfy the demand of our clients. There’s only so much we can do with temporary-type resources. You really need to have the core people in here in order to deliver the quality our clients demand,” he said.

Back in Wisconsin, Fredrich is also looking for a core staff of his own — low-skilled laborers he’s willing to train and pay above minimum wage.

“What they need to be able to do is come to work on time every day, pay attention to what they’re doing, take instruction well, and just put in an honest day’s work,” he said.

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals