The Federal Reserve’s policy pivot this week may be too late to save an economy that is suddenly struggling to avoid grinding to a halt.

For the first time since before the financial crisis, short-term government bonds are yielding above their longer-duration counterparts, a tell-tale recession sign called an inverted yield curve.

But it’s more than that: Spending, investment and manufacturing data have weakened considerably. Friday brought a fresh round of troubling signs when Purchase Manager Index readings in the euro zone pointed to contraction, bringing another round of worry that a deteriorating global picture could drag down the U.S.

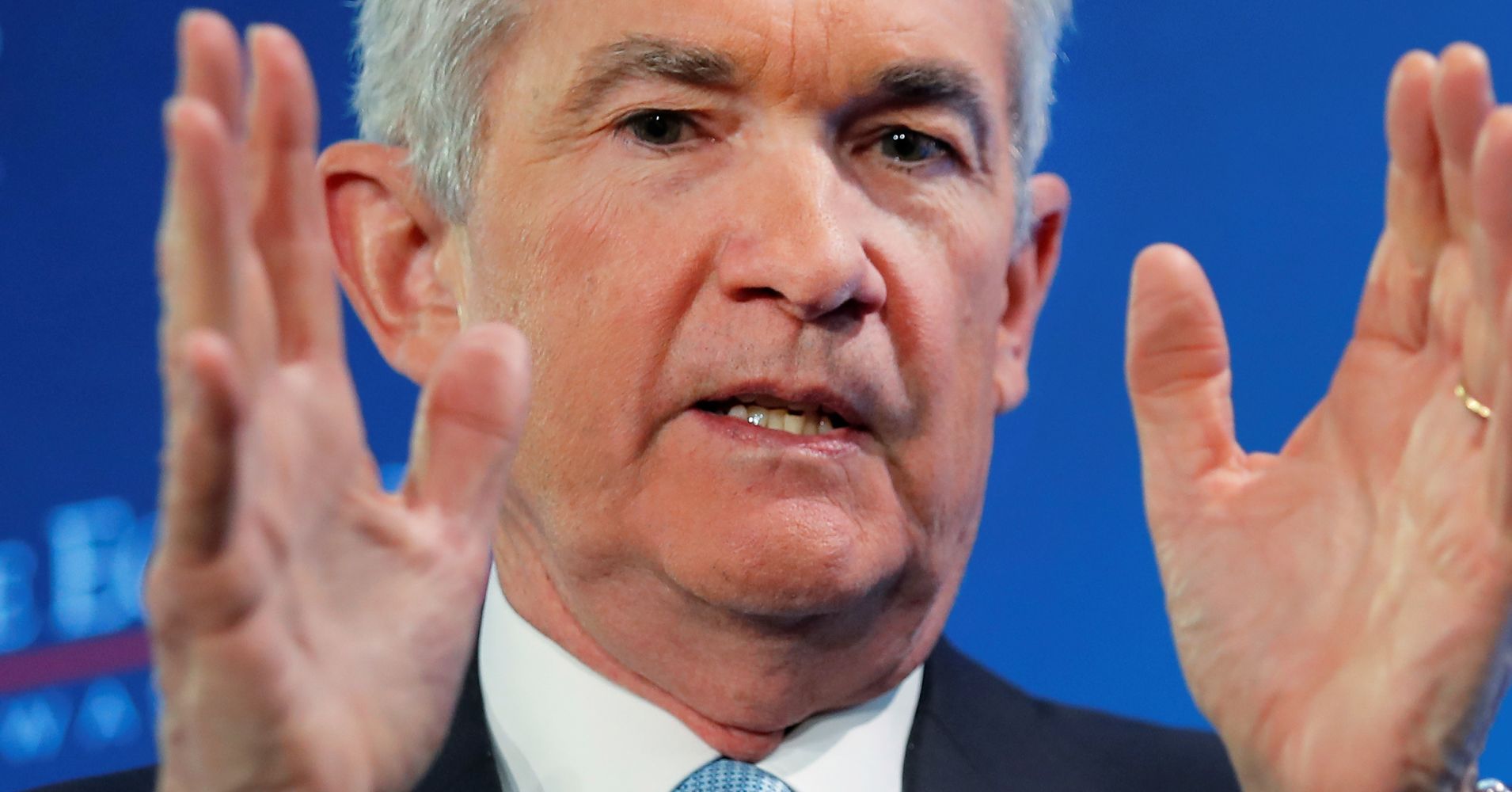

In the midst of it all comes the Fed, where officials badly wanted to normalize the extremely accommodative policy used during and after the financial crisis and now find that their expectations will have to be tempered. Chairman Jerome Powell and his fellow central bank officials said they likely will not carry through on intentions to hike rates two more times this year, and will end the process of reducing the bond portfolio on the Fed balance sheet much sooner than expected.

Rather than take assurance that the Fed would come to the rescue again, market participants instead are beginning to wonder if that’s still possible.

“They’re trying to soft-land the economic plane, and the fundamental problem is they’ve never been able to do it,” said Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics. “There’s only so much they can do. I don’t think they can save the day.”

Indications, in fact, are that the Fed will have to do more than hold the line on its benchmark funds rate, which is now targeted in a range of 2.25 percent to 2.5 percent.

Traders were anticipating that a rate cut actually could be on the horizon, assigning a 57 percent chance of one quarter-point reduction — and even a nearly 18 percent probability of two cuts before the end of the year, according to the CME’s tracker of trading in federal funds rate contracts.

That’s especially remarkable considering that Powell and others just a few months ago were expressing concern about the economy overheating and the need to cushion against excesses.

Powell stunned markets in October with his comment that the Fed was “a long way” from a neutral rate that was neither stimulative nor restrictive on growth, implying that multiple rate hikes were still ahead. Now, central bank officials may think “the current neutral rate is even lower than previously believed,” Andrew Hunter, senior U.S. economist at Capital Economics, said in a research note.

That belief would jibe with action in the bond market, where traders have pushed the 10-year note to around 2.45 percent, a level it last was in early 2018 before an inflation scare took root. There seems little, at this point, that the Fed can do to stem if not a recession than at least growth slower than many had anticipated.

“The bottom line is that the Fed’s recent climbdown will not be enough to prevent economic growth from slumping to below its potential pace this year,” Hunter said.

Things could get bad enough, Hunter added, that he sees the Fed approving as many as three rate cuts in 2020.

To be sure, there are still few if any economists who think an actual recession is near.

Zandi, the Moody’s economist, said the current jobs market is strong enough that it suggests an economy that is “struggling” rather than one in recession.

Likewise, Joe Brusuelas, chief economist at RSM, figures it will be a “near-miss” on a recession, but said the Fed’s recent actions show it is “preparing for a change in framework.”

One of the central bank’s problems is that, with its funds rate now trading around 2.41 percent, it has little wiggle room in the face of another downturn. Brusuelas estimates the Fed needs about 650 basis points of room to cut rates during an economic pullback or recession and now has less than 250.

“So we’re going to be back in the world of unconventional policy,” he said. “This is real big stuff.”

That realization comes just a year after the economy grew around 3 percent and the White House is predicting around the same for 2019, an expectation that already looks like it won’t be met. The Atlanta Fed’s GDP tracker is suggesting just 0.4 percent growth in the first quarter, setting up math that will be hard to overcome the rest of the year.

Asked if he thought the Fed, through its own cut to GDP expectations for the full year to 2.1 percent from 2.3 percent, was indicating that growth already has peaked, Brusuelas said, “That’s exactly what the Fed is saying.”

“I don’t begrudge them for the conservative stance they are taking. They’re trying to thread the needle,” he added. “Mr. Powell is going to have to choose his own path. We’re all going to have to live with that.”

Signal2forex review

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals