Executive Summary

Regardless of one’s position on the necessity of three consecutive rate cuts this year, the way the FOMC’s hand was played looks reasonably favorable with the benefit of hindsight. The recession warning from an inverted yield curve has gone from flashing red to yellow as some positive slope has returned to the curve.

Having now entered the blackout period when Fed officials refrain from public comment, we offer our latest installment of our Flashlight for the FOMC Blackout Period. We expect the FOMC will keep rates unchanged at its December 11 meeting. With the Fed signaling it will be on hold for at least its upcoming meeting, the focus has already shifted to what comes next. With “insurance” taken out, it will now come down to how the economy is performing. The December meeting will also provide an update to the FOMC’s economic outlook through its Summary of Economic Projections. Based on the most recent data, we do not anticipate any meaningful adjustments to GDP and unemployment projections for this year or next.

With respect to the balance sheet, we expect that the Fed will eventually create a standing repo facility (SRF) that will be available on a “permanent” basis. But because we do not expect that any SRF will be operational until next year, we think it is a bit premature to expect that technical details of such a facility will be announced at next week’s meeting.

The Economy Has Decelerated, But Not Markedly

Starting with the first rate cut in almost a decade in July, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) has followed on with two more cuts in successive meetings. The top end of the fed funds range is now at 1.75%, 75 bps lower now than it was in the first half of the year.

At the beginning of this current rate-cutting campaign, it was not entirely clear that the economy was in need of rescue. Consumer spending was strong, and, while hiring may have cooled, the labor market was still tight with the unemployment rate near a 50-year low. But, inflation measures had been running a bit below the Fed’s target rate, which offered policymakers the justification to cut rates and remain within the spirit of the dual mandate.

The FOMC has made no secret about the primary reasons for the rate cuts: concern over slowing global growth and worries about what that could mean for the economic outlook, even if coincident measures suggested the economy is still in good health. But those risks have eased over the past month or two. After a sharp escalation in the trade war, talks for at least a partial deal have resumed. In addition, the imminent risk of a hard-deal Brexit has also subsided.

Meanwhile, the economy continues to weather current headwinds. Global growth remains anemic, but the latest purchasing managers’ indices from the Eurozone and China suggest momentum is at least not worsening. The same largely holds true in the United States, where the ISM manufacturing index remains below the demarcation line separating expansion from contraction, but data on core capital goods orders hint at a modest rebound in business investment in the current quarter.

Perhaps most importantly, there are few signs of slow global growth and investment weakness spilling over into the labor market. Job growth was stronger than expected in October and prior hiring was revised significantly higher. All told, job growth does not appear to be slowing to the extent feared. The continued strength in the labor market suggests only a modest deceleration in consumer spending after the breakneck pace of growth this summer.

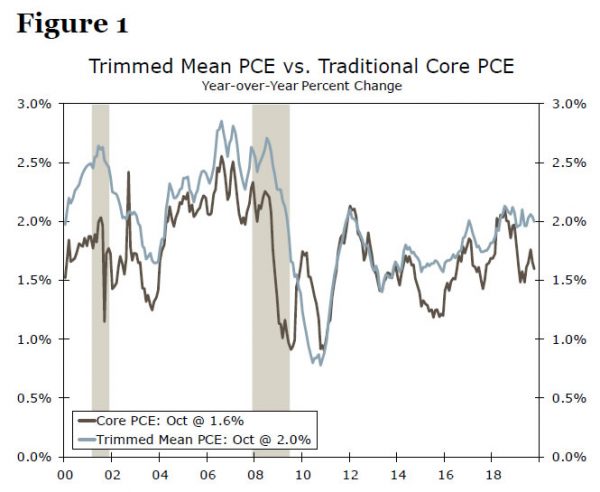

Despite the recent rate cuts, however, inflation has remained subdued. Core PCE inflation dropped back to 1.6% year-over-year in October after two soft monthly readings of 0.1%. That said, longterm market and consumer inflation expectations remain unaltered, while the Trimmed Mean PCE deflator shows the underlying trend in inflation remains at 2.0% (Figure 1).

Regardless of one’s position on the necessity of three consecutive rate cuts, the way the FOMC’s hand was played looks reasonably favorable with the benefit of hindsight. The recession warning from an inverted yield curve has gone from flashing red to yellow as some positive slope has returned to the curve. Financial conditions have eased since early October and remain accommodative relative to pre-crisis norms (Figure 2). Overall, the economic and financial data since the Fed’s last meeting suggest the expansion remains positioned to continue.

What Rate Decision is on Tap for December?

We expect the FOMC will keep rates unchanged at the December 11 meeting. After perhaps some of the most discordant meetings of the cycle, policymakers appear to be back on the same page. FOMC members in the “insurance” camp appear satisfied for the time being with the 75 bps of easing done to date. After all, risks have leveled off to some extent, and it will take some time for the accommodation to work its way through the economy. Meanwhile, members who were more apt to cut only once weakness in the U.S. economy became more evident are not so worried about high inflation or financial imbalances to push for taking back recent cuts. And so, the FOMC likely will remain on hold on December 11.

Financial market participants appear to be on board with the “on hold” signal coming from the committee. Currently, markets are pricing in only a 5% chance of a rate cut in December. At the same time, equity markets are hovering near all-time highs, credit spreads are near the year’s tightest and financial conditions remain broadly accommodative. In other words, markets do not appear to think the economy is in need of further support at this time.

The Dot Plot: Looking Ahead to 2020-2022

With the Fed signaling it will be on hold for at least its upcoming meeting, the focus has already shifted to what comes next. With “insurance” now taken out, it will come down to how the economy is performing. Said differently, it is back to data dependency rather than risk dependency. Chairman Powell noted during his press conference following the last FOMC meeting that the committee will need to see a “material” weakening in the outlook before cutting rates again.

The December meeting will also provide an update to the FOMC’s economic outlook through its Summary of Economic Projections. Based on the most recent data, we do not anticipate any meaningful adjustments to GDP and unemployment projections for this year or next (Figure 3). The median estimates for both GDP and the unemployment rate should remain favorable relative to longer-run estimates. Expectations for core inflation may sink a bit further below 2%, however. With inflation still expected to struggle to meet 2%, let alone rise above it for a time to demonstrate the “symmetric” nature of the target, we would expect the Fed to maintain its easing bias.

The easier policy stance the FOMC has settled upon is likely to become evident in the dot plot (Figure 4). The fed funds rate is already below the median estimates for 2019-2022. The extent to which the dots shift lower over the next few years will offer some clues as to whether officials think they can reverse this year’s “mid-cycle adjustment”.

What Else Does the FOMC Have on Its Plate?

Although discussion tends to center around what the FOMC will decide regarding its target range for the fed funds rate, there has been no shortage of action with its balance sheet tools as well. Following a surprising amount of volatility in money market rates in mid-September, the Fed announced its intention to purchase T-bills at least into the second quarter of 2020 with a stated objective of maintaining reserve balances “at or above the level that prevailed in early September 2019.” As we noted in a report at the time, the move should not be interpreted as a return to quantitative easing (QE). Through its QE purchases, the Fed intended to put downward pressure on long-term interest rates. In contrast, by pumping liquidity into the banking system via its purchases of short-dated T-bills, the new operation is intended to prevent a re-occurrence of volatility in money market rates. Although we believe that the FOMC will want to keep its options open, at least through the end of the year when short-term funding pressures seem to be greatest, we will be watching for any guidance that the committee may give regarding its planned purchases in the first few months of 2020.

Not only did the Fed announce T-bill purchases to relieve funding pressures, but it also has been conducting overnight and term repurchase operations (repos) as a tactical maneuver. As we wrote in our aforementioned report, we expect that the Fed will eventually create a standing repo facility (SRF) that will be available on a “permanent” basis. But because we do not expect that any SRF will be operational until next year, we think it is a bit premature to expect that technical details of a such facility will be announced at the conclusion of next week’s meeting.

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals