U.S. Review

Virus Shutdowns Begin to Show Up in the Data

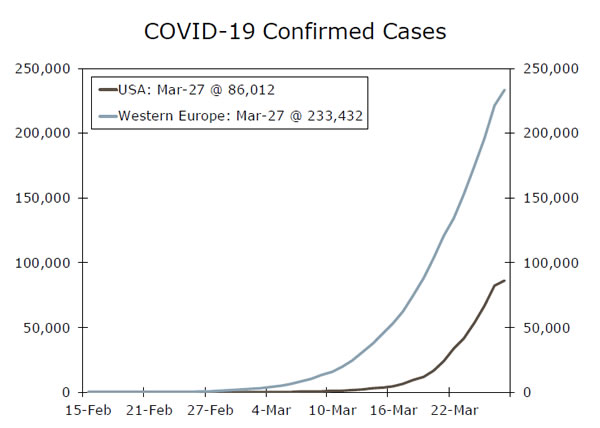

- The U.S. surpassed Italy and China with the most confirmed cases of COVID-19. Europe is still the center of the storm, with the total cases in Europe’s five largest economies topping 230,000.

- The impact of virus-related shutdowns became readily apparent in this week’s initial unemployment claims, which soared to 3.3 million.

- Most economic data reflect the period before the COVID-19 outbreak intensified in mid-March. New home sales averaged their strongest pace in over 12 years during the three months ended in February, while consumer spending rose modestly.

From Full Throttle to Sudden Stop

The economic carnage produced by the abrupt shutdown of economic activity across the country is readily apparent from the weekly unemployment claims. Jobless claims had been running at their lowest levels since the late 1960s, before jumping to 282,000 during the second week of March and then surging to a record 3.3 million during the week ended March 21. As bad as the current claims data are, the numbers are likely to climb even higher next week. California reported that claims rose one million this week and noted that claims offices were overwhelmed and the actual number may be higher. Job losses were broad-based, with hotels and restaurants; arts, entertainment and recreation; and healthcare and social assistance leading the way. Manufacturing layoffs also increased. Ohio, Pennsylvania and California reportedly led the rise, although almost all states likely posted large increases. Most of this week’s economic reports reflected the period prior to when the COVID-19 outbreak intensified. The economy appears to have been in solid shape then, with some areas, such as housing, booming. New home sales fell 4.4% in February but January’s sales were revised significantly higher, leaving February’s level of sales above the consensus estimate. New home sales have averaged a 763,000-unit pace the past three months and prospective buyer traffic was reported to be brisk as recently as early March. There is little doubt that the abrupt halt to economic activity and spike in layoffs will pull sales lower in coming months and might also lead to some cancelations to previously signed purchase contracts. We lowered our forecast for home sales and new home construction but do not expect homebuilding to be the eye of the current economic storm. Home sales and new home construction are more likely to be part of the solution to this economic slump than be the primary source of the problem.

Consumer spending for February came in roughly in line with expectations, although inflation-adjusted outlays rose just 0.1%. We reduced our forecast for GDP growth but still see modest growth during the first quarter due to the strength seen earlier in the year. Quantifying the nearly complete pullback in consumer spending, aside from grocery stores, is extremely difficult, however, and it is certainly possible that the plunge in activity during the second half of March will overwhelm all the growth that occurred earlier in the quarter. We see real GDP plunging at a 14.7% annual rate during the second quarter and a 6.3% annual rate during the third quarter. Estimates for Q2 growth vary, however, as there is no precedent for what is now occurring.

The critical question is how long this economic carnage will last? The answer depends on how the virus progresses in the U.S. and around the world. The U.S. recently surpassed Italy and China with the largest number of confirmed COVID-19 cases. Testing has ramped up considerably, with 97,806 tests completed yesterday and 418,500 done this past week. The ramp-up in testing is one reason confirmed cases increased so dramatically. Europe may be a good roadmap for the United States. Europe accounts for the bulk of the COVID-19 cases outside of China and the number of cases ramped up there a couple of weeks ahead of the U.S. The growth in new cases has moderated ever so slightly but has not flattened out, casting doubt on the more optimistic forecasts for the U.S.

U.S. Outlook

Consumer Confidence • Tuesday

It is hard to feel confident about current economic conditions when so much of the economy is currently closed. It is perhaps even harder to feel confident about future economic conditions when it is unclear when those closures and shelter-in-place orders will be lifted. Millions of Americans are currently homebound, either working remotely or recently unemployed, giving them extra time to focus on the rapidly deteriorating public health situation as well as their rapidly falling 401(k)s. That does not bode well for confidence.

Estimating the magnitude of the drop is difficult. The survey was conducted in the first part of March, meaning it predated some of the worst news regarding case totals and business closures. It also predated progress on the fiscal rescue package, which should shore up consumer finances, at least temporarily. Yet the damage to confidence from a global pandemic and mass unemployment may prove to be quite long-lasting.

Previous: 130.7 Wells Fargo: 109 Consensus: 114

ISM Surveys • Wednesday & Friday

Similar to consumer confidence, the March ISM surveys will be bad, but their early-March survey dates may exclude some of the most severe declines in activity which occurred over just the past couple weeks. It is also worth noting that they are diffusion indexes, which capture the breadth of activity change, rather than the magnitude. In the simplest of terms, the ISM services index is designed to capture the number of restaurants seeing fewer customers; it is unable to capture the fact that many restaurant saw sales fall to zero. This means that the certain declines we will see in the ISM indices will actually understate the extent to which activity contracted in March.

Expecting the services PMI to fall further is a reasonable bet, given that consumer-facing industries have been the most affected, but don’t expect manufacturing to be spared—Boeing and the major automakers have all been forced to suspend production.

Previous: 50.1; 57.3 Wells Fargo: 41.0; 39.0 Consensus: 46.0; 48.0 (Mfg.;Non-Mfg.)

Jobless Claims & Payrolls • Thurs. & Fri.

Jobless claims went vertical this week, making even the Great Recession look like a mere blip. The data are unprecedented because the situation is unprecedented—a coordinated, governmentmandated shutdown of entire sectors. Nearly 3.3 million people filed for unemployment insurance for the week ended March 21, and we expect the number for the following week to also be in the millions, for a number of reasons. Just one example of what is still to come— Governor Newsom reported one million claims in California alone over the past two weeks, despite the Department of Labor reporting only 187K claims in California in its latest report.

The weekly claims data are timelier than the monthly nonfarm employment, especially for tabulating the magnitude of such an abrupt shutdown. The March employment survey was conducted the week ending the 14, meaning we still expect modestly positive growth. The April report will be historically bad.

Previous: 273K Wells Fargo: 50K Consensus: -81K (Change in Nonfarm Employment)

Global Review

Virus Hits Eurozone Data; Global Growth Downgraded

- This past week, March PMI surveys for the Eurozone were released, with data suggesting a sharp deceleration in the broader European economy is likely. The services PMI fell to a record low of 28.4, while the manufacturing PMI dropped to 44.8, which signals the Eurozone economy could contract more than 4.0% in 2020.

- As the COVID-19 virus intensifies, we downgraded our international growth forecasts once again. We now expect annual contractions in the U.K., Japan as well as Canada, and forecast China to experience its first annual contraction since at least 1980.

Eurozone Gets a Glimpse of Virus Impact

As the COVID-19 virus continues to spread, many of the larger countries within the Eurozone have seen infection rates increase more than the rest of the world. In particular, Italy has seen confirmed virus cases and death rates rise significantly. According to data compiled by Johns Hopkins University, over 80,000 Italian citizens have been infected, with over 8,200 fatalities. In addition to Italy, confirmed cases in Germany, France and Spain have increased dramatically as well. In response to the spread of the virus, authorities across the Eurozone have implemented measures such as lockdowns, travel restrictions and more stringent social distancing protocol in an effort to contain the virus. The European Central Bank has also taken action, extending its asset purchase program and implementing other forms of easier monetary policy, while countries such as Germany and Italy have pledged additional fiscal spending to combat the potential effects of the virus.

This week we received a bit more clarity on the possible economic impact the Eurozone may face in the near future. On Tuesday, PMI surveys were released with these data signaling the impact on the Eurozone economy could be quite severe. The Eurozone March services PMI fell to a record low 28.4 from 52.6 in February, even weaker than the consensus forecast which was looking for a reading of 39.5. Meanwhile the manufacturing PMI also fell noticeably to 44.8 in March, from 49.2 in February. While PMI data are some of the first indicators we have received since the virus intensified the way it did, we can still gather a lot of information about the economic slowdown that is likely imminent at this point. Should the PMI surveys stay around current levels, or fall further, a Q2 GDP decline of more than 8% quarter-overquarter annualized, perhaps extending into a double digit decline, appears well within the realm of possible outcomes. With that in mind, we recently updated our GDP and inflation forecasts and now believe the Eurozone economy will contract 4.2% in 2020 and forecast deflation of -0.1% this year.

Global Growth Forecasts Turn More Negative

In addition to the Eurozone, we downgraded many other growth and inflation forecasts as well. We now expect full-year economic contractions across the G10, more specifically in the United Kingdom, Japan and Canada. In addition, we now forecast a 2.0% contraction in India as Prime Minister Modi ordered countrywide isolation and social distancing, and also forecast a 4.8% contraction in Mexico this year as lower oil prices, border restrictions and a U.S. recession weigh on the Mexican economy. Our latest forecasts also indicate a full-year contraction of 1.2% in China, which is relatively significant as China has not experienced an annual contraction since at least 1980. Most of this contraction reflects the downturn in Q1 as a result of the virus originating in a major Chinese province and the subsequent lockdown that was put in place by Chinese authorities. Some of the restrictions are starting to be alleviated and manufacturing is starting to come back online, but with a deep economic contraction in Q1, it will be difficult for China to dig out of the hole and experience positive annual growth this year.

Global Outlook

China Manufacturing PMI • Monday

The impact of the COVID-19 virus has already started to appear in some of China’s economic and sentiment indicators. In particular, the manufacturing PMI experienced a significant downturn in the month of February as business closures and other efforts to contain the spread of the virus were put into effect by the Chinese authorities. Next week we will get an update of the manufacturing PMI survey, which according to consensus forecasts, is expected to rebound in March. A rebound makes sense as businesses within China are beginning to re-open, travel restrictions are being lifted and manufacturing is starting to come back online. However, despite restrictions being lifted, the manufacturing PMI is likely to remain in contractionary territory in March and likely until the Chinese economy is up and running back to pre-virus levels. We may see a more significant rebound later in the year as the virus dissipates and China begins operating at more normal rates of output.

Previous: 35.7 Consensus: 45.0

Chilean Central Bank • Tuesday

Over the course of the last few months, central banks around the world eased monetary policy rather aggressively in an effort to offset the potential economic impact from the COVID-19 virus. The Chilean Central Bank has not been an exception to this trend, cutting rates 75 bps at an off-cycle meeting earlier in March. Looking ahead to next week, we believe it is likely that the central bank will look to cut interest rates again. Commodity prices, in particular copper, continue to move lower which will drag on the economy while we believe the economy may begin to see additional disruptions as a result of the constitutional rewrite process getting underway in April. In our view, the Chilean Central Bank has limited monetary policy space and lacks room to lower interest further without causing a sharp selloff to the Chilean peso. Should it cut interest rates once again, we would expect the currency to come under additional pressure going forward.

Previous: 1.00%

Canada Manufacturing PMI • Wednesday

One of the economies that is likely to come under serious pressure this year is Canada. While the virus in itself will certainly play a role in causing a deceleration, the sharp selloff in oil prices as a result of tensions between Saudi Arabia and Russia are also likely to have an influence over the health of the Canadian economy. As of the end of March, global oil prices are about 60% lower with Western Canada Select oil trading below $10 per barrel. Depressed oil prices could result in an economic contraction in Q1, while the combination of lower oil prices, border restrictions and a slowdown in the United States will likely result in an annual GDP contraction in 2020. On Wednesday, we will get our first glimpse into how bad the slowdown will be when manufacturing PMI data are released. In February, the manufacturing data remained in expansion territory, but given how oil prices have collapsed and how the virus has intensified we would not be surprised if the PMI fell into contraction.

Previous: 51.8

Point of View

Interest Rate Watch

What’s Going on With LIBOR?

As we discussed in a report that we wrote on March 16, the FOMC slashed its target range for the federal funds 100 bps in surprising fashion on Sunday, March 15. The target range is now back to 0.00% to 0.25%, where the FOMC maintained it for seven years following the financial crisis in 2008. Yet businesses and households that borrow at rates that are calculated as some spread over LIBOR have not seen lower interest rates. As shown in the top chart, 3-month LIBOR has actually risen since the committee cut rates. Moreover, the spread between 3-month LIBOR and the yield on the 3-month Treasury bill, which has averaged about 30 bps over the past few years, has pushed out to more than 120 bps. This is the widest spread since the record 463 bps during the depths of the financial crisis in October 2008. What’s going on?

The reason is related, at least in part, to the stresses in the financial system at present. Not only have major stock indices moved significantly lower, but spreads on corporate bonds (over U.S. Treasury securities) have widened considerably. In short, investors have turned risk averse due to the uncertain economic effects of the COVID-19 outbreak. This risk aversion and the associated desire of banks to maintain ample holdings of liquidity have pushed LIBOR higher.

Recall that LIBOR is an unsecured rate. That is, LIBOR reflects the interest rate that a bank would charge another bank for a loan on an unsecured basis. In contrast, T-bills are among the safest securities in the world, and their yields generally decline when risk aversion spikes. Indeed, SOFR, which is a secured rate—borrowers must pledge Treasury securities as collateral—is closing in on 0.00%. As we describe in a report we wrote in January, SOFR is slated to replace LIBOR as the benchmark interest rate at some point in the next few years.

If the history of the financial crisis is any guide, LIBOR should drift back down to more “normal” levels in coming weeks and months as tensions in financial markets ease. Lower borrowing rates will provide some cushion to households and businesses.

Credit Market Insights

There Is a First Time for Everything

This week, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) announced a range of measures to support households, businesses and the overall U.S. economy. These actions included ramping up its quantitative easing program and re-instating some programs that were created during the financial crisis such as the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF). Beyond its already established programs, the FOMC also announced that it will be creating two facilities, the Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility (PMCCF) and the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF). The PMCCF is aimed at supporting the issuance of investment grade corporate bonds, and allowing companies access to credit so that they are better able to maintain business operations and capacity amid disruptions related to the coronavirus outbreak. Meanwhile, the SMCCF will provide liquidity for outstanding corporate bonds. This is the first time, of which we are aware of, that the Fed provided direct support to the corporate bond market.

Credit spreads in the corporate bond market have widened significantly and are trading at their widest since the 2008-2009 financial crisis (bottom chart). An index of investment grade bonds jumped from about 130 bps over U.S. Treasury securities in mid-February to about 450 bps earlier this week. But the FOMC’s two new facilities may be helping to bring life back to the corporate bond markets. Spreads started to recede this week, and issuance in the investment grade market has soared. Issuance in the high-yield market has not yet returned, but that should happen eventually if financial market tensions continue to subside.

Topic of the Week

Congress Unleashes the Fiscal Firehose

Late Wednesday night, the U.S. Senate unanimously passed a landmark fiscal bill designed to keep the U.S. economy afloat amid the drastic measures taken to combat COVID-19. The house is scheduled to vote today, and assuming no hiccups the president could sign the bill into law as early as this evening. The bill’s combination of direct checks to households, expanded unemployment benefits, grants/loans to various levels of government and generous loans to U.S. companies should help ease what is likely to be a significant decline in U.S. total income. Although we do not yet have an official score from the Congressional Budget Office, the bill currently working its way through Congress appears to be about $2 trillion in size, or roughly 9% of U.S. GDP, nearly double the size of the stimulus passed in February 2009 during the Great Recession (top chart). But, even this may understate the true size of the package. Our reading is that roughly $454 billion of that money will be used as an equity infusion into a Federal Reserve 13(3) emergency lending program designed to lend directly to ‘Main Street’, e.g. businesses, states & municipal governments. Assuming the Fed uses the equity to lever up about ten times, that would generate more than $4 trillion in lending power. The actual deficit impact, however, will likely not be as large as even the rough $2 trillion headline figure, because many of the loans in the bill will be paid back over time. Still, from a near-term standpoint, the deficit and net Treasury issuance are set to explode. Our latest federal budget deficit forecasts for FY 2020 would put the deficit as a percent of GDP near levels not seen since World War II, when budget deficits peaked around 25%-30% 0f GDP (bottom chart).

In recent report, we delve into a more in-depth summary of the bill, as well as its implications for the economy. In short, the passage of this fiscal stimulus bill gives us reasonable confidence that another Great Depression is not in the cards, and that a bounce back in economic growth will occur starting this fall. But, even these extraordinary measures can only do so much, and the economic contraction in the months ahead is likely to be quite severe. This is not to say the policies are ill-designed, but rather that until the COVID-19 outbreak is in check, fiscal and monetary policymakers are just buying time until the economy can begin to reopen.

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals