With the rupee hovering close to its all-time weakest level against the U.S. dollar, India’s central bank is widely expected to hike interest rates this week to shore up the currency.

The rupee has been the worst-performing Asian currency this year, losing around 14 percent against the greenback on the back of higher U.S. interest rates. But a slew of new troubles in the financial sector could spur the Reserve Bank of India to leave the currency unaided, opting instead to keep rates unchanged when it announces its monetary policy decision scheduled on Friday.

“RBI will probably stay put in the upcoming meeting, in contrary to consensus,” analysts from Mizuho Bank wrote in a Monday note. “RBI does not appear to be inclined to lift rates just to protect (the Indian rupee) unless there is clear evidence that a weaker currency has pushed up imported inflation.”

The reason the central bank would let its currency continue to languish, according to the analysts, is that it’s more worried about the stability of India’s financial institutions. Those concerns have been brewing for several months, but they came to a head in the last few weeks with the near-collapse of a non-bank lender called Infrastructure Leasing and Financial Services (IL&FS).

That firm, a large infrastructure financing company, missed several debt repayments and triggered a series of defaults and ratings downgrade. In turn, investors sold bonds and stocks in the non-bank finance space — also known as the shadow banking sector — for fear that such problems may be more widespread in the industry.

Non-bank finance companies have been a growing source of loans to Indian companies at a time when banks have held back lending to clean up their troubled holdings worth around $150 billion.

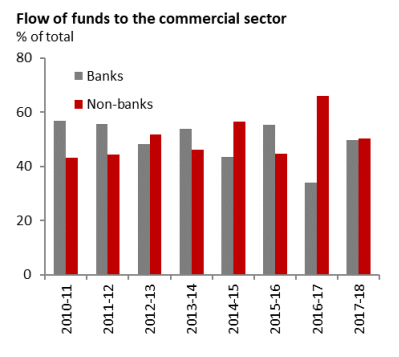

There are now more than 11,400 shadow banking companies with a combined balance sheet worth around 22.1 trillion rupees ($304 billion) and their loan portfolios have grown at nearly twice the pace of banks, according to Reuters. In 2017, such lenders accounted for 66 percent of the funding provided to India’s commercial sector, up from 44 percent the year before, according to a report from Radhika Rao, economist at DBS Group Research.

Source: Reserve Bank of India, DBS Group Research

But non-bank lenders may find it more difficult to source for funds in the wake of the IL&FS defaults as investors stay away from the sector. And unlike banks, those firms are not typically allowed to hold deposits and don’t have access to the extensive network of bank-to-bank funding.

Problems in the shadow banking space add to concerns that the overall financial sector in India may find it harder to support a fast-growing economy. India’s roughly $2 trillion economy is the third-largest in Asia and is expected to expand by 7.3 percent this year — one of the fastest-growing globally, according to a World Bank report in June.

“It makes life a lot more difficult for RBI, clearly,” Mitul Kotecha, senior emerging markets strategist at TD Securities, told CNBC last week.

“We know the banking sector issues in terms of recapitalization have been ongoing for a while, but this is non-bank financial sector … and I think that could have a bigger impact on liquidity,” he said, adding that the Indian central bank would want to calm worries by ensuring there’s enough supply of money in the financial system.

Indian authorities have already begun to intervene. The government said on Monday it would replace IL&FS’s board and ensure the company has the money to repay its debt estimated at $12 billion, Reuters reported. The RBI has also stepped up efforts to increase money supply in the economy.

Some analysts predicted the central bank will prioritize fixing the financial sector in its policy meeting this week, forecasting no changes to India’s interest rates. Raising rates would make it more difficult for businesses and households to repay their debt and reduce the availability of funds — which will hurt the financial sector further.

“We believe that financial stability is a more immediate concern,” Shashank Mendiratta, an economist at ANZ, wrote in a note last week. “Although the combination of higher oil prices and a weak rupee have raised concerns about the inflation path, the recent soft inflation prints suggest that the RBI can afford to wait and see. Stabilising the rupee by raising interest rates does not appear high on the agenda.”

But such analysts are still apparently in the minority. A Reuters poll of 64 experts found that 29 of them expected India’s benchmark policy rate to stay at 6.5 percent, with the remaining 35 forecasting a hike of between 25 and 50 basis points.

“We still can’t underestimate the potential inflationary impact of ongoing currency depreciation,” ING economist Prakash Sakpal wrote in a note last week. The Dutch bank, which took part in the Reuters poll, expects the RBI to raise interest rates by 25 basis points.

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals