Wherever Mark Connors looks at markets, from stocks to currencies to oil, he sees signs of the unknown.

Equity investors got whipsawed this week during two rough and volatile sessions, but Connors, global head of risk advisory at Credit Suisse, had seen worrying signs long before that. A key technical measure he tracks, the correlation between the price of stocks and currencies, had broken down starting in April. That, along with sharp drops in the price of oil, point to one thing, he says: Uncertainty about the future as central banks around the world unwind programs that bought trillions of dollars of assets.

“We’re seeing two of the biggest asset classes, stocks and currencies, exhibit a degree of uncertainty in their relationship in 2018 that we’ve never seen before,” Connors said. “Crude just exhibited something very unusual in the context of the last 40 years.”

The unwinding of central banks’ programs a decade after the financial crisis brought economies to the brink is known as quantitative tightening. J.P. Morgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon said in July that one of his biggest fears is around how markets would behave as central banks removed their unprecedented stimulus.

“If quantitative tightening continues, guess what’s going to happen? More of this,” Connor said, referring to unusually violent moves across markets.

Another factor in the speed of recent declines is the result of several important changes that have happened since the last financial crisis.

Automated trading strategies from quant hedge funds and the massive shift to passive investing have helped to remove liquidity from the system in times of panic, according to Marko Kolanovic, J.P. Morgan’s global head of macro quantitative and derivatives research. He said in a September note that index and quant funds made up two-thirds of assets under management globally and the majority of daily trading.

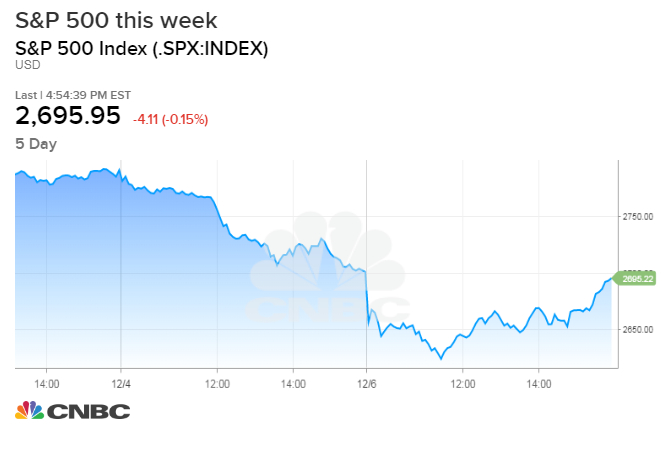

So when investors begin to sell, as they did on Tuesday amid concerns over the state of U.S. trade talks with China, the moves were probably amplified by computerized trading strategies. Selling intensified that day after the S&P 500 fell below its 200-day moving average, a key technical measure.

Before the next trading session on Thursday, equity futures plunged, prompting the CME Group to halt trading more than three dozen times. Markets continued to slide: At one point the Dow plunged almost 800 points before recovering after a news report that the Federal Reserve may take a more cautious approach to future rate hikes.

As experts grasp for explanations on these unnerving moves, some are calling for help. Billionaire hedge-fund manager Leon Cooperman, founder of Omega Advisors, blamed the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission for allowing machines to dominate markets.

“I think your next guest ought to be somebody from the SEC to explain why they have sat back calmly, quietly, without saying anything and allowing these algorithmic, trend-following models to wreak havoc with what has, up to now, been the best capital market in the world,” Cooperman said in a CNBC interview.

He and others have called for the reinstatement of the uptick rule, which restricted short selling to stocks that traded higher at least once between short orders. The rule was repealed in 2007, just in time for the financial crisis. Since then, during times of sharp distress, market commentators have wondered aloud why the rule went away.

John Nester, a spokesman for the SEC, declined to respond to Cooperman’s comments.

“Uncertainty is here, and that means deleveraging into a market with reduced liquidity,” Connors said. “Expect more of these exacerbated moves.”

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals