In mid March, the statements appeared in a sequence on the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission’s website. “SFC reprimands and fines Merrill Lynch Far East Limited $128 million for sponsor failures.” “SFC reprimands and fines Morgan Stanley Asia Limited $224 million for sponsor failures.” Standard Chartered Securities: $59.7 million. UBS: $375 million. Not a significant sum, you think, but enough to send a message. And then you realize they’re talking in Hong Kong dollars.

They do things differently in Asia. The combined total of HK$787 million for transgressions while sponsoring Hong Kong IPOs is equivalent to about $100 million between four banks; the StanChart fine is equivalent to just $7.6 million, or about 0.001% of the bank’s assets. Even UBS’s fine, representing half the total, is equivalent to only 1% of its 2018 net profit. It’s a far cry from American fines, where they hit French banks so hard the fines become significant cross-border capital flows.

But in Asia it’s always much more about the shame than the amount, something which was also made very clear in Singapore with the fines levied on private banks over 1MDB. The numbers do not make the slightest dent in anyone’s numbers, but the embarrassment of being named and reprimanded is intense.

UBS comes out of the SFC investigation worst, not only fined but with its licence to advise on corporate finance partially suspended for a year. (Partially? This means it cannot be a sponsor of Hong Kong listings – this suspension was already in place while UBS was being investigated.) Also, one of its former staff, Cen Tian, has his licence suspended for two years.

UBS is principally in trouble for its role on the China Forestry listing in 2009, a deal in which Standard Chartered was reprimanded; and Tianhe Chemicals in 2014, in which both Morgan Stanley and Merrill Lynch (now BAML) were reprimanded. China Forestry has been suspended since 2011 – it is now in liquidation – and Tianhe Chemicals has been suspended since 2015. UBS is also penalized for its role on another unnamed deal, thought to be the 2009 IPO of China Metal Recycling Holdings, though this has not been confirmed.

One problem with the China Forestry deal was that, to put it bluntly, the sponsors failed to verify whether it actually owned any trees. StanChart at least conducted some site inspections in Sichuan and Yunnan – three times, in fact – but not enough to verify claims in the prospectus. UBS, it is now apparent, didn’t carry out any physical inspections after joining Stanchart as a sponsor, and although it claimed to have done so earlier as a joint bookrunner, it couldn’t provide any inspection records or even say where it had gone.

Red flag

Tianhe Chemicals was an issue of inadequate due diligence and a failure to follow up some very obvious warning signs. All three of the reprimanded banks had interviewed Tianhe customers, but Tianhe had informed them which customers they would interview face-to-face and which they would not. The banks didn’t ask why some customers didn’t want to be interviewed at their offices.

Then, the three sought to interview the largest customer of Tianhe at its office and were rebuked on the grounds that an anti-corruption campaign was under way in mainland China and therefore third parties could not visit its premises – a curious argument. So they set up an interview with the customer at Tianhe’s office.

The next sentence, from all three SFC statements on the banks’ penalties, is telling: “At the end of the interview, the representative of customer X refused to produce his identity and business cards and stormed out of the meeting room. He told [the banks] that he would not have agreed to be interviewed under customer X’s internal procedure, and he only attended the interview to help the family of Tianhe’s chief executive officer.”

Though this was surely a mighty red flag, none of the banks followed up. Several months later, a potential cornerstone investor in the deal told Merrill it had done its own due diligence on the same customer, phoning his general line only to be told that no such person existed. Again, the banks did nothing of any consequence to verify. The banks are also called out for unclear interview questions.

Where does this take us? It shows that the SFC has teeth and is prepared to look a decent distance back in time to penalize misbehaviour, which sends a message to those conducting Hong Kong IPOs today. It suggests that underwriters, and most specifically sponsors, will be held to account for imploding deals from China, even if investors find themselves with no recourse when they collapse.

And though it embarrasses all four banks, they will be glad to see the matter behind them. (There might be more: in October the SFC said it had issued nine sponsors with decision notices about intended enforcement measures, which may include small fines levied on Citigroup for Real Gold Mining’s IPO in 2009, and China Construction Bank International for the 2014 failed Fujian Dongya Aquatic IPO.) UBS’s statement spoke of being “pleased to have resolved these legacy issues relating to our Hong Kong IPO sponsorship licence.”

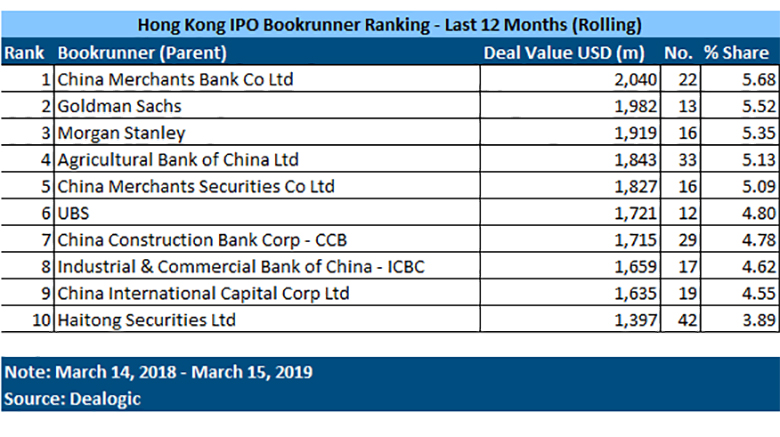

The truth is, none of them have really been impacted by the allegations in terms of winning new deals: even UBS’s sponsor ban does not appear to have had a huge impact on its ability to take bookrunner roles in Hong Kong. Data commissioned by Euromoney from Dealogic shows that in the 12 months to March 15 2019, Morgan Stanley ranks third among Hong Kong IPO bookrunners and UBS fifth.

They certainly won’t be feeling it in the bottom line.

NOTE: If you want to trade at forex professionally – trade with the help of our robot forex developed by our programmers.

Signal2forex review

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals