Highlights

- Oil prices have staged a steady recovery since the start of the year, rising by more than 50% from their December lows.

- While a good part of the comeback can be traced to broad improvement in risk sentiment, a tightening in the supply-demand balance for crude suggests that recent price levels are sustainable.

- The outlook for oil demand is mixed. Demand growth has recently been weakening, especially in OECD countries. Still, fears of a protracted global slowdown have moderated and expectations for 2019 are pointing to improving growth.

- Supply-side factors, however, are taking center stage. OPEC+’s compliance in implementing a 1.2 million bpd cut and involuntary reductions in other countries have been the key driver in supporting a return to a somewhat more balanced market.

- OPEC spare capacity, together with the persistent rise of U.S. shale production and its relatively low break-even costs will serve to put a ceiling on any meaningful price acceleration from here.

- Accordingly, our price outlook for WTI remains that of a relatively flat, range-bound profile between US$60 to US$65 throughout the next two years. With respect to Canadian benchmarks, all signs point to a widening of the WTI-WCS differential in the medium term.

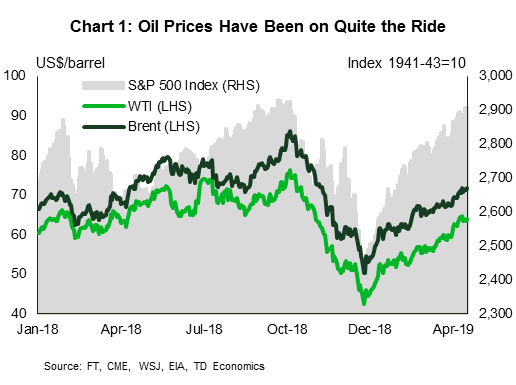

Global oil prices have been on a wild ride over the past year. After peaking at a four-year high of US$76 last October, the price of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) tumbled more than 40% at the end of 2018 (Chart 1). Since then, prices have staged an impressive comeback, with WTI returning back to the US$66 level. The rally coincided with improving risk sentiment as well as reduced recession risks and expectations of stabilizing demand. Still, a more important influence has been on the supply side, where cuts by OPEC+ have effectively eliminated a sizeable production surplus in the global oil market. Indeed, total world crude oil supply is now estimated to be around 2.5 to 3.1 million bpd below its peak in November 1.

With prices now running generally in line with fundamentals, we expect that WTI and other global benchmarks are likely to trade side-ways over the next few quarters. In our view, any move above the top end of the US$60 to US$65 range is likely to prove short-lived. In such a scenario, we would expect supply to enter the market rather quickly. The outlook for Canadian oil benchmarks is slightly less favourable, with the discount on the WCS benchmark expected to widen going forward (see Box 1). This forecast reflects longstanding transportation issues, the fading impact of the curtailment plan, and the recent drop in crude-by-rail shipments.

Box 1: Update on Canadian Oil Benchmarks

Canadian oil spreads have narrowed remarkably since the Alberta government announced a plan to curtail production last December. Since then, prices have comfortably followed the rally in global benchmarks, with the WTI-WCS spread stable and averaging an unusually narrow US$10 since the start of the year. The curtailment plan is intended as a temporary solution to a supply glut problem that sent discounts to record levels last fall, including on lighter oil variations and synthetic crude. Starting in February, production limits have been gradually eased as a response by the government to improving prices and inventory reductions at the time.

Still, we doubt that this low discount can be sustained in the near and medium term amid still-high inventories and a recent collapse in crude-by-rail shipments. Media reports and announcements by some producers have suggested that the recent spread levels (around US$10) are too low to justify the marginal cost of crude-by-rail shipments (at around US$15-US$20 range). This recent drop in energy export volumes2 and crude-by-rail shipments will likely slow down the inventory draws in the near term, thus adding further uncertainty (Chart 2). Indeed, the discount has widened (albeit only slightly) in the past two weeks, now sitting closer to US$12.5.

Longer term, demand side drivers for Canadian heavy oil remain relatively strong, with a large proportion of U.S. refineries configured for heavy oil as feedstock. Given that U.S. production is primarily of a lighter variant (WTI) and that alternative heavy oil sources are lacking and/or declining, this should maintain stable demand for Canadian heavy oil in the foreseeable future.

A lack of pipeline capacity remains a key longer-term barrier to Canadian heavy oil prices. A recent delay to Line 3, initially relied on to start operations by the end of 2019, has added to the uncertainty – with the pipeline now expected to be completed in the second half of 2020. At the same time, there has been minimal progress on the TransMountain (TMX) and Keystone XL pipelines from a regulatory perspective. A Federal decision on TMX is expected (albeit not guaranteed) in June. Other factors contributing to forthcoming uncertainty include the potential cancellation of additional rail capacity planned by the previous Alberta government, which would erase around 120K of planned transportation capacity, and the International Maritime Organization regulations on sulphur caps coming into effect next year (IMO 2020).

On the whole, we believe that the current discount on Canadian heavy oil is likely too low, and continue to expect that it will widen again to levels near US$15-US$20 range by year-end. This forecast reflects the fading impact of the Alberta curtailment plan (and the easing in production limits), the potential impact of the recent drop in crude-by-rail shipments and export volumes on inventories, and the lack of progress on transportation and pipeline capacity. With pipeline delays still on the horizon and with the production curtailment plan winding down, crude-by-rail continues to be the marginal option for transportation, justifying a discount in the aforementioned range.

Risk sentiment has improved since late 2018

Heading into last summer, market participants were feeling quite optimistic about oil prices. By October, the price for a barrel of WTI and Brent oil had risen around US$16 and US$20 dollars from the outset of the year, respectively. But with the start of autumn came an abrupt change of scenery. In a matter of 12 weeks, WTI fell from a high of US$76 to a trough of US$42, catching market participants and producers by surprise. Much of this change coincided with sudden souring in the global economic outlook and risk appetite.

Since December, risk sentiment has notably improved, and was matched by a similar movement in oil markets. For instance, net non-commercial positions in oil futures (used as a proxy for speculative positions) have bounced back sharply, though not reaching the peak levels posted during last year’s price run-up (Chart 3). While the timing of WTI’s drop and consequent rebound has been identical to that of other major risk assets (including the S&P 500 Index as shown in Chart 1) the magnitude of the swing has been relatively pronounced.

Underlying the broad tailwind to prices from the ‘risk-on’ behavior so far this year has been a steady tightening in the crude supply-demand balance. In the second half of 2018, daily world production was exceeding consumption by as much as 2.5 million barrels per day, pushing up global inventories sharply. The excess daily output has been swiftly addressed since the start of the year.

Demand expectations are mixed, but stabilizing

With the increased global uncertainty last year came both a significant lowering in near-term global GDP growth and oil consumption projections. The IMF’s recent World Economic Outlook placed world growth at 3.3% in 2019 (Chart 4). This is a further downgrade from October (3.7%), and equates to over US$300 billion removed from global GDP. Our sensitivity analysis suggests that a 0.3 ppt shock to global GDP growth results in around a 200K bpd drop in global oil demand (Chart 5).

On the plus side, recent data, such as that for global business sentiment surveys, have started to turn the corner. A pause in rate hikes and a dovish tilt by major central banks has been supportive for growth expectations going forward. In addition, renewed Chinese stimulus and infrastructure spending is expected to support improved sentiment in 2019. At the same time, worries around an escalating China-US trade war have dissipated and so too have fears of a looming recession. This bodes well for a firming in oil consumption later this year.

Drilling down on demand by country reveals that China, India, and the U.S., are driving a significant chunk of the growth in demand in the last few years (Chart 6). For these countries, consumer and manufacturing-related growth is still holding relatively strong. It is demand from advanced economies (ex-U.S.) that is at risk, including Japan, South Korea, and European countries. This coincides with IMF’s forecast, which cut growth expectations the most in advanced economies.

Putting the demand picture together, growth forecasts (y/y) are ranging from 1.2 to 1.4 million bpd in 2019 as a whole3. We expect that growth in 2019 will be at the lower end of this range, given our relatively conservative 3.2% global growth forecast. Stabilizing global GDP growth should be enough to at least keep demand stable over the near-term forecast horizon and prevent it from slipping significantly below this range.

Supply-side factors are doing the heavy lifting

The more prominent factor behind oil’s fundamental turnaround is the supply side. Total world supply has fallen by more than 2.5 million bpd since its peak in November – mostly due to planned and unplanned OPEC+ cuts. OPEC+, led by Saudi Arabia, has reduced output even more than its 1.2 million bpd commitment at its December meeting in Vienna. Compliance for most producers in OPEC+ has been running well above 100%4. Saudi Arabia’s output alone has dropped more than 1 million bpd, with further drops in most OPEC+ countries. Unplanned and involuntary drops also brought some supply off the market due to the ongoing crisis in Venezuela (more than 400K bpd). In Canada, the mandated government curtailment plan in Alberta, which is home to the oilsands, has seen raw crude oil and bitumen production drop on average of -275K bpd in Q15 (see Box 1 for a detailed analysis on this).

The return to deficit territory (Chart 7) of the daily global supply-demand position has removed a key roadblock depressing oil prices. Inventories have been slow to respond, given their elevated starting point6 and the glut formed by the end of 2018. However, signs of tightening and stabilization are starting to emerge. For instance, OECD inventories have reduced (albeit slowly), and are are now narrowing in on their five-year average.

A recent development, whereby the U.S. fully eliminated all waivers on sanctioned Iranian oil is expected to further deepen the deficit in the near-term. Still, any such upward impact on prices and balances should not linger for long, especially with OPEC’s spare capacity now at upwards of 3 million barrels per day7 and with U.S. shale production being relatively elastic. Historically, OPEC has offset unexpected reductions in global oil supply (Chart 8). With the recent elimination of Iranian waivers, we expect that OPEC+ will gradually reverse some of the recent cuts over the second half of the year, following its June meeting.

On the flip side, U.S. shale production is likely to continue to grow. Average annual production was more than 500K bpd higher than initial estimates in 2018. The EIA forecasts production will increase by around 1.4 million bpd in 2019 and another 0.7 million bpd in 20208. The comparable rate posted in 2018 was 1.6 million bpd. This would result in a significant supply build, though a lesser one than that which occurred in 2018. This slowdown in production growth is consistent with the number of oil rigs in operation. Here we have seen a modest decline since the autumn 2018 price slump (Chart 9). Rig counts remain well below their elevated pre-2014 investment surge levels. It is important to note that the elasticity of shale output to price changes is relatively high, and rig counts will likely be quick to respond to any expectation of sustained price increases.

Results from the quarterly Dallas Federal Reserve Bank Energy Survey suggest that the breakeven price to profitably drill a new well sits in the US$48-US$54 range (Chart 10), with an average of US$50. Indeed, rig counts declined in the fall of 2018 as prices dropped below that range. Of course, U.S. shale is not the sole determinant of prices, but with relatively low breakeven levels, it is now assumed to be a significant force in keeping prices range-bound. This marginal cost to drill a new well in U.S. shale provides an anchor to our price forecast.

Price outlook

In sum, the crude oil market appears to be in a sweet spot with oil prices improving closer to their longer-term fundamental level, output growing in line with consumption, and stockpiles on track to be worked off towards historical norms. As such, our base case assumes that WTI prices will trend in the US$60-US$65 (Chart 11) range within the next two years. This range also implies that oil prices will continue to trade at a premium to the marginal cost of new U.S. shale production. Our base case relies on near-term global growth expectations holding firm at around 3.2% and that OPEC+ maintains some of the cuts put in place last December in the coming months in order to keep the supply-demand fundamentals in balance.

Upside risks to the forecast are mostly centered on wildcards, namely supply disruptions and geopolitical factors. This includes further drops in Venezuelan output, disruptions in Libya and Nigeria, or a larger than expected impact of Iranian sanctions on the crude market, which could force the risk premium implied in the price of oil higher. On the downside, the most notable risk is a deeper than projected slowdown in global growth as well as a renewed wave of pessimism in global financial markets.

End Notes

- Based on data from Energy Intelligence Group (OMI) and the International Energy Agency’s April Oil Market Report.

- Statistics Canada mentions that the late reporting of crude oil transactions means that statistics on this data must be estimated in the current month’s (February’s) release. See: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/190417/dq190417b-eng.htm

- This is based on the most recent forecasts from: IEA, EIA, OPEC, and Energy Intelligence Group (OMI).

- Based on data from the IEA and Energy Intelligence Group (OMI).

- See: https://www.alberta.ca/oil-production-limit.aspx

- Caused by elevated output levels by the world’s three largest producers (Russia, Saudi Arabia, U.S.) combined with reduced demand growth at the time.

- Based on data from the IEA’s April Oil Market Report. See: https://www.iea.org/media/omrreports/fullissues/2019-04-11.pdf

- Based on the latest EIA Short Term Outlook Report. See: https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/steo/

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals