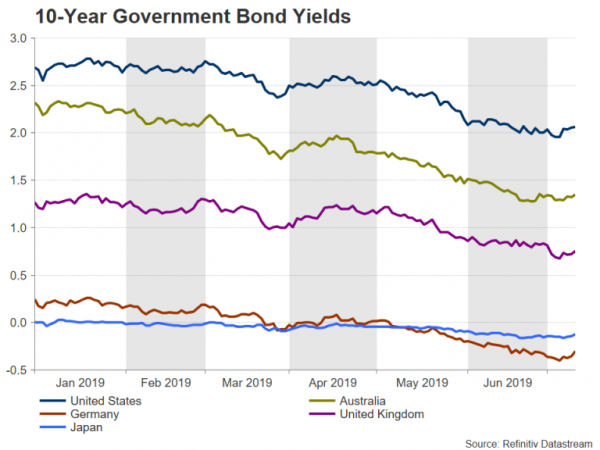

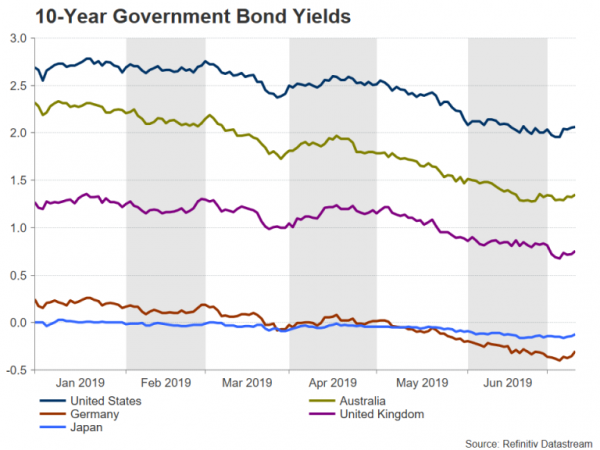

As sovereign bond yields around the world take a nosedive in anticipation of rate cuts by major central banks, the question once again being asked is how low can interest rates go. With rates in many regions such as Europe and Japan already in negative territory, have central banks run out of adequate scope to conduct effective policy easing?

Bond yields tumble on recession fears

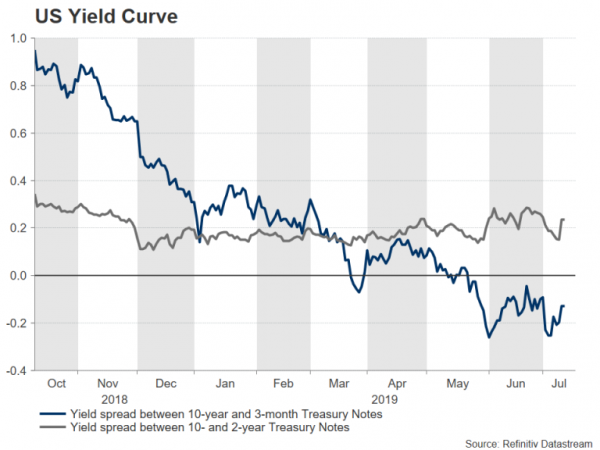

Slowing growth and worries of a possible recession in the United States and elsewhere have driven traders to aggressively price in substantial rate cuts by the major players in the world of monetary policy. But while there are notable signs of market stress, as indicated by the partial inversion of the US yield curve and German bunds falling to record lows below zero, the growth picture so far hasn’t been quite as bad as many have predicted.

The latest data out of the US show the economy is still expanding at a comfortable pace, albeit at a slower one. Growth in the euro area and Japan has also held up relatively well. Even the UK, where Brexit remains a major source of uncertainty, has so far avoided a negative quarter in GDP growth. But there are concerns that the second half of 2019 will be much more challenging.

Global growth outlook deteriorating

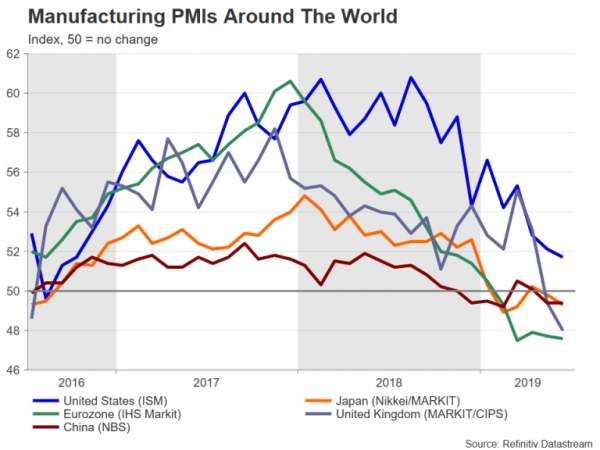

Those investors hitting the panic button would point to the continued downtrend in the PMI indicators, particularly in the manufacturing PMIs, which have fallen to contractionary territory in most European and Asian countries. The ongoing trade tensions and the fading chances of a quick resolution to the Sino-US dispute are likely to weigh on world trade for the rest of the year. This means export-reliant economies such as Germany and Japan could easily slip into recession in the coming quarters if there’s no positive developments that could help revive falling business confidence.

But it’s not just the manufacturing sector that’s experiencing a slowdown (if not an outright recession). There are signs the broader economy is also faltering in many countries. The US’s ISM non-manufacturing PMI hit a near two-year low in June and the services PMI in the UK is dangerously close to the 50-neutral level. In Japan, falling wages pose a risk to already weak conditions for domestic consumption.

Yield curve inversion worries markets and policymakers

But the most talked about indicator, which is considered by policymakers and market participants alike as a reliable foreteller of a recession, is the yield curve inversion. The yield spread between 10-year and 3-month Treasuries, which has turned negative before every recession since the Second World War, has been inverted since May. The longer the spread between the two remains negative, the higher the risk of a recession.

This particular part of the yield curve is watched closely by the New York Fed in its own gauge of calculating the odds of a recession. But this may still not be sufficient to convince all the hawks at the Federal Reserve that things are bad enough to warrant aggressive policy action. Some policymakers may wait to see an inversion of the 10- and two-year yield curve for a more conclusive warning that things are not right in the US economy.

Fed easing a foregone conclusion

Although it’s unclear whether everyone in the Federal Open Market Committee is on board for a rate cut, the consensus among market participants is that there will be at least a 25-basis points reduction at the July meeting, with Fed Chairman Jerome Powell cementing those views in his semi-annual testimony to Congress this week. The bigger question, however, is whether two or three pre-emptive rate cuts by the Fed will succeed in abating fears about a US and global recession.

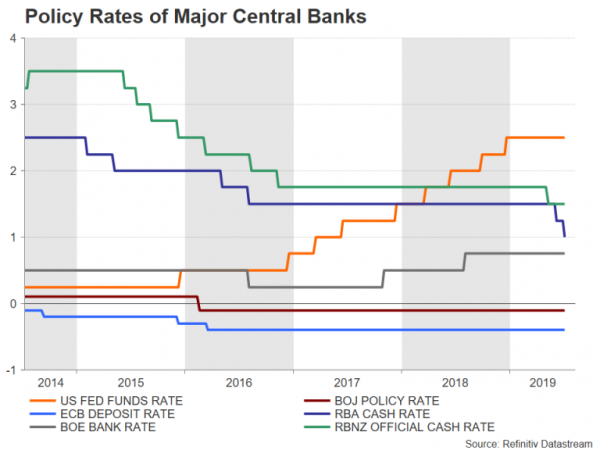

The Fed has less bandwidth to cut rates this time round than in previous occasions when the economy was past the peak of the business cycle. It would be perfectly natural, therefore, for the Fed to not want to make dramatic reductions in interest rates when the economy is still expanding. However, if there was a coordinated effort by central banks globally to increase monetary policy accommodation, policymakers may just succeed in warding off a steep downturn without having to resort to unconventional and untested policies.

Can rates in Eurozone and Japan go any lower?

But this is more of a problem for the likes of the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan where rates are already sub-zero. The ECB is expected to embark on a fresh round of policy easing in the coming months. But with the deposit rate currently at -0.40%, the ECB perhaps can only afford to cut rates by another 30 bps or so before it risks damaging the profitability of commercial banks operating in the Eurozone. The BoJ has a similar dilemma, which possibly leaves quantitative easing as a more attractive option for the two central banks.

However, there’s a real danger that more QE would not be as effective as it was the first time round during the financial crisis back in 2008-09. There’s also doubts as to how effective negative interest rates are with the evidence so far from Japan and the euro area pointing to only limited success in lifting inflation.

Race to the bottom

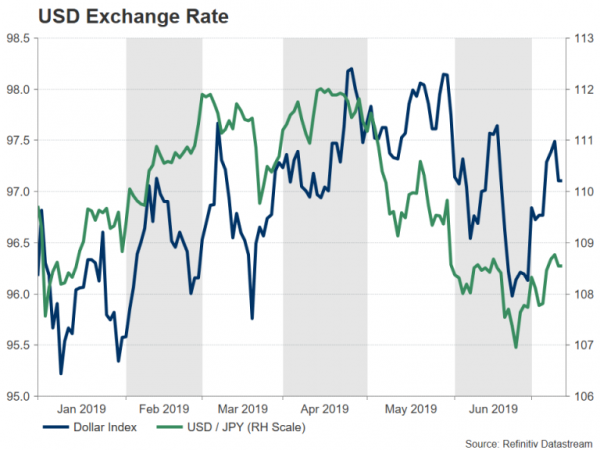

This raises the question of how central banks would respond to an actual recession or even a new global economic crisis. The Fed at the moment has the most room to cut before rates fall to zero again, hence the US dollar’s recent depreciation.

The Reserve Banks of Australia and New Zealand were the first to make insurance cuts and it would only take a few more moves before they reach zero. However, both the RBA and RBNZ got through the financial crisis without the need for QE and so are not facing the same risk of diminishing returns like the ECB and BoJ if they decided to begin asset purchases. The Bank of England has a bit more leverage than its European counterparts, but a potential chaotic UK exit from the European Union could force it to restart QE. As for the ECB and the BoJ, the only way out for these economies from a severe downturn may be more fiscal rather than monetary stimulus.

Dollar’s decline may not be sustainable in long run

But for the currency markets, whether policy easing involves deeper negative rates or more QE is perhaps not as relevant as the big picture, which is that all the major central banks, reluctantly or proactively, are moving towards a more accommodative policy stance. While this may produce wild short-term swings, there is not a great deal to support the view that the longer-term trend will change as well. The US economy remains and is expected to stay in much better shape than its peers. Even with substantial Fed rate cuts, US yields are likely to remain above those of other nations’, potentially putting a floor under the greenback.

For now, though, the dollar is likely to face more downside pressure than the other majors, while the yen has the most to gain. The BoJ has not only failed to give clear signals that it will loosen policy in the near future, but any move could merely consist of minor tweaks or not very powerful changes to its existing stimulus programme. This probably leaves the yen vulnerable to more upside risks than its peers in the short- to medium-term.

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals