Financial markets have been thrown into a tailspin in recent days on news that the COVID-19 outbreak is spreading beyond China. Market participants fear that the outbreak will lead to slower economic growth in most countries, the United States included, and the U.S. bond market is now fully priced for 50 bps of rate cuts by the Federal Reserve by autumn. Yet many rightly question how Fed rate cuts can help the situation. Lower interest rates could help if the Fed had tightened too much, but it is hard to make a convincing case that short-term rates are excessively high at present. Moreover, lower interest rates will do little to open factories that have been temporarily shuttered because workers have been quarantined.

As we have written in a series of reports, we believe that potential supply chain disruptions could have more of a depressing effect on the U.S. economy than the demand-side effect of weaker export growth. And observers are correct to question how effective Fed rate cuts would be in combatting supply chain disruptions. Yet easing by the Fed would not be completely ineffective.

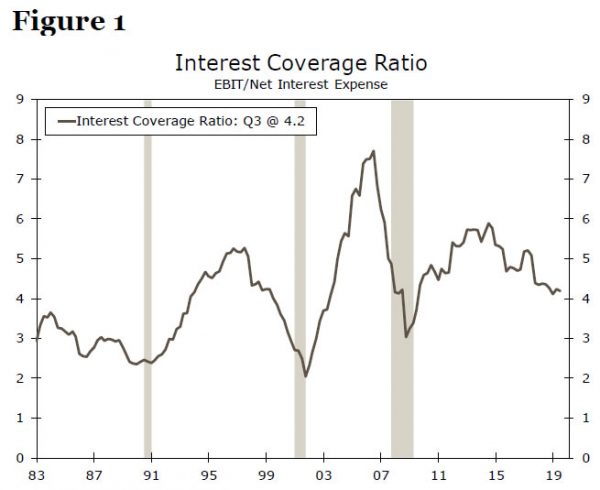

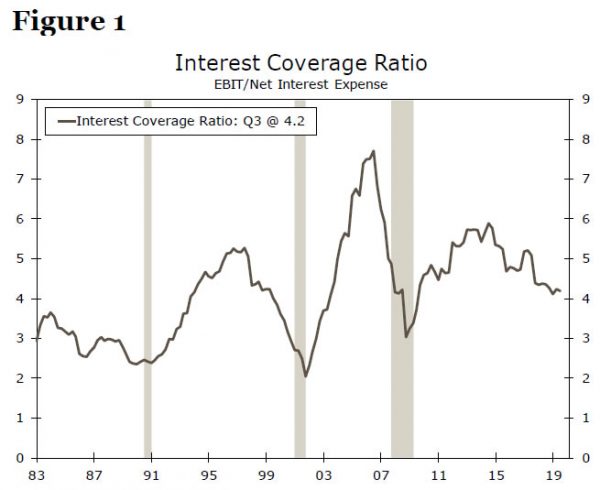

For starters, lower short-term interest rates would provide some support to the U.S. business sector via lower interest costs. As shown in Figure 1, the interest coverage ratio for the non-financial corporate sector, which measures the amount of cash flow that businesses have to service their debts, has trended lower in recent years. Lower interest rates would also help to shore up net income, thereby reducing the need for businesses to displace workers in an effort to conserve cash flow.

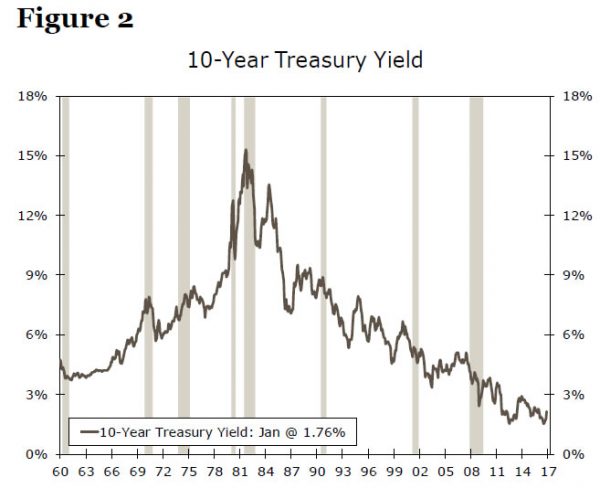

In addition, many mortgage rates are tied to the yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury security, which has nosedived to an all-time low of only 1.33% due, at least in part, to anticipation of lower shortterm interest rates (Figure 2). This drop in the benchmark Treasury yield should put some downward pressure on mortgage rates, which should spur re-financing activity, thereby freeing up more income for consumer spending.

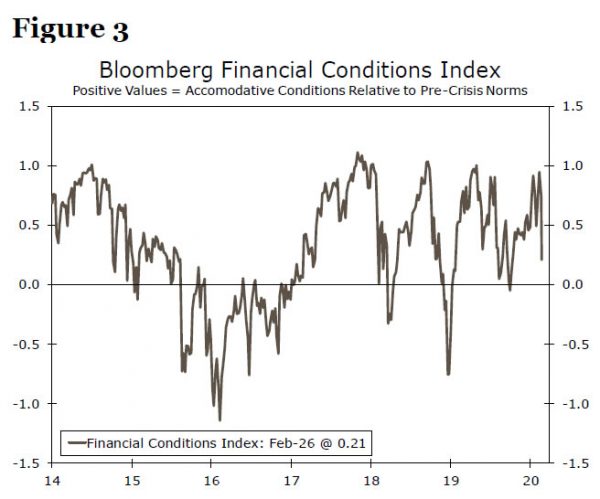

Furthermore, as measured by the Bloomberg Financial Conditions Index, financial conditions have tightened recently (Figure 3). Specifically, the U.S. stock market has come under selling pressure in recent days, and spreads on corporate bonds have widened. If this financial market volatility is sustained, banks could begin to tighten lending standards on new loans. Rate cuts by the Federal Reserve could offset some of the tightening that has already occurred in financial markets.

As we noted in a recent report, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) likely would cut rates by more than 25 bps in total if it decides that more accommodative policy is warranted. The FOMC has had six easing cycles during the past 30 years, and each time the committee cut rates by at least 75 bps over the course of the easing cycle (Figure 4). Moreover, the bond market is fully priced for 50 bps of rate cuts by autumn, so if nothing changed financial markets could tighten further if the FOMC under-delivered. That said, financial markets could dial back their expectations of Fed easing if COVID-19 does not spread as widely as some market participants now fear.

Obviously, the situation involving COVID-19 remains very fluid, which makes the economic outlook unusually uncertain. Federal Reserve policymakers have acknowledged that they are closely monitoring the situation, and they will be poring over incoming economic data to ascertain the effects that the outbreak may be having on the U.S. economy. If economic data remain solid and financial markets stabilize, then the FOMC very well may remain on hold. But if the outbreak were to spread unabated and financial markets tighten further, then the Fed likely would end up cutting rates later this year, if not sooner. Stay tuned.

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals