It’s Brexit season again and amidst the blitz of coronavirus and US election headlines, Brexit is the other topic that’s prominent in news feeds at the moment as new deadlines approach. But deadlines have come and gone before, and each time people hoped Brexit is done and dusted. However, this time, it really is the final battle round and if there is no deal in the coming weeks, Britain will default to trading with the European Union on WTO terms as of January 1, 2021, losing all of its membership privileges.

So close, yet so far

Markets have lost count of the exact number that the latest round of talks taking place in London this week has reached. But all investors need to know is that the negotiations are now in the final stages, with disagreements on fisheries, a level playing field and governance being the last remaining potential deal breakers.

The EU’s chief negotiator, Michel Barnier, has warned that there are plenty of other areas where significant gaps still need to be bridged. But most of those differences will probably be settled as the talks progress. After all, Boris Johnson’s version of Brexit is very different to what Theresa May had in mind when she was in charge.

Has the EU let itself be outmanoeuvred?

May’s big ambition was to have as frictionless trade as possible after Brexit. Although that would have minimised the Brexit pain for UK companies, it would have involved extremely complicated talks to set up a new customs union from scratch that would be unique to UK-EU trade. Johnson’s vision, on the other hand, is ideologically closer to a ‘hard’ or ‘clean-break’ Brexit and the future trade pact that’s in the works will probably resemble the deal that the EU recently made with Canada.

The EU initially welcomed Johnson’s clearer and simpler approach to Brexit. It has definitely speeded up the negotiations as the more basic the trade agreement is the smaller the new rule book would have to be. But the EU may now be realising that by mocking May’s Brexit and inadvertently opening the door for Johnson to take over as prime minister, it has lost too much leverage in the talks.

It’s France vs Britain in the final round

For instance, as the negotiations head for crunch time, it is looking more and more like fishing rights are becoming the most contentious issue. Whereas with the Withdrawal Agreement, its fate rested with Irish politicians north and south of the border – something which the EU fully exploited to its advantage – it is the centuries-old ‘sibling rivalry’ between France and the UK that could sink a deal on a post-Brexit trade agreement.

The English Channel is an important source of fish stock for French fishermen and under EU law, they’ve been allowed to fish in British waters for decades. That is all about to change as Britain transitions out of the single market at the end of the year. Britain wants to regain full control of its waters once it has permanently severed its membership links with the EU. France is having none of that.

Fishing row could scupper a deal

But does France really have much of a say in the matter? The UK has already made it clear it does not mind a hard Brexit and there are many Brits, including within the government, who would be thrilled at the prospect. Johnson even reiterated this week that if there is no outline of a deal by October 15, the UK will walk away from the talks.

All these suggest that if compromises are going to be made in the final weeks of negotiations, it will most likely be the EU that will have to bend more. If fishing rights do really end up being the last obstacle towards an agreement, it’s hard to imagine Germany will be too happy to let French pride jeopardize a deal, especially as fishing accounts for a very small portion of both French and UK GDP.

The ball is in the EU’s court

But another emerging sticking point in recent rounds of discussions is the dispute over a level playing field, and specifically, about how state aid will be regulated post Brexit. This may appear like a bit of an odd issue given that British governments are generally not in favour of state interventions to bail out private sector companies. In fact, it is more common for certain EU members such as France to breach the bloc’s subsidy rules. Nevertheless, Brussels is worried that if decisions on state subsidies are left entirely to Westminster, the UK might gain an unfair competitive advantage.

With time fast running out, the EU knows that the ball is in its court, and feeling pressured by Johnson’s tight deadline, it’s been trying to push the negotiations into November. But regardless of whether that crucial 11th hour arrives on October 15, or in November or even on December 31, the question is, who will blink first?

UK’s rush for a deal

In the previous negotiations, it was the UK side that caved in too quickly. In 2018, Theresa May was so keen to get a deal and stick to her timetable, she failed to consult Northern Ireland’s DUP party that was propping up her government about the controversial backstop. A year later, Boris Johnson was so desperate to put his stamp on May’s Withdrawal Agreement and get rid of the backstop, he didn’t bother reading the legal fine print to understand the extent to which Northern Ireland would have to be regulated by EU single market rules if the backstop is ditched.

Fast forward to 2020 and the circumstances have changed significantly. It is no longer about the terms of the divorce but the legal text that will define all aspects of the future relationship between Britain and the EU. And while Britain is still divided as a country on Brexit, this time, Johnson’s government has a strong majority in Parliament and could easily survive by laying all the blame on the EU if the negotiations were to collapse. Not only that, the UK has had more time to prepare for a no-deal scenario and therefore has less to fear from abandoning the talks should it feel that the price for a deal is one too many compromises to its sovereignty.

Is a skinny deal on the cards?

As the talks intensify in the coming days and weeks, this is something that Barnier might want to stay conscious of. There is no doubt that the UK has more to lose from a disorderly Brexit than the EU. But having a ‘rogue state’ that makes its own rules at its doorstep is not an appealing prospect for the EU.

However, it’s worth pointing out that although Johnson, in his determination to stick to his election pledge and get Brexit done before year-end, may just succeed in getting the EU on board, he could be foregoing a deal that is better than a ‘Canada-style’ agreement. There is a risk that not even a ‘Canada-style’ free-trade agreement might be possible in the rush to reach an accord in such a short timetable and there is talk in the markets that as things stand, a ‘skinny deal’ is a more realistic outcome.

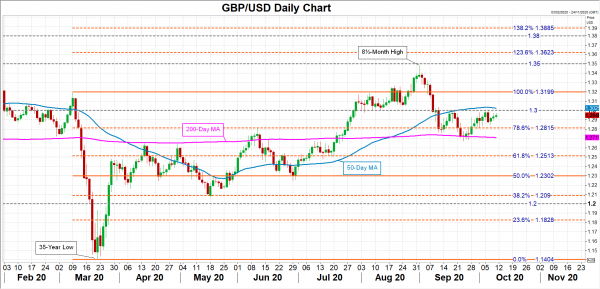

Limited upside for the pound

If a basic free-trade deal is the best the two sides manage to achieve, the pound’s anticipated relief rally that follows is likely to be brief. Cable could ascend as high as $1.35 but a climb beyond that resistance area would probably be a stretch, especially if the virus situation were to worsen.

It is possible of course that, despite all the negative headlines, a more comprehensive trade agreement is struck, in which case the ensuing rally could extend towards $1.38, with further gains again being dependent on how well the UK economy is recovering from the pandemic.

However, in the event of a no-deal outcome, the $1.20 level is the key support that could be revisited and stand in the way of a steeper freefall in the currency.

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals