The Bank of Japan will conclude its first monetary policy meeting of 2022 on Tuesday and publish an updated set of economic forecasts. So far, the BoJ has been excluded from the global central bank race to normalize policy amid skyrocketing inflation in many parts of the world. However, with price pressures swelling in Japan too, the January meeting might see the Bank take a baby step towards the hawkish side. The question is, would a slightly less dovish stance do much for the yen’s prospects in the short term?

BoJ may soon get its wish of untaming inflation

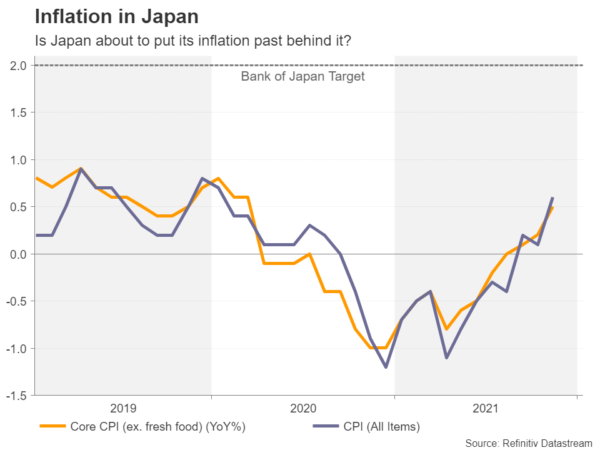

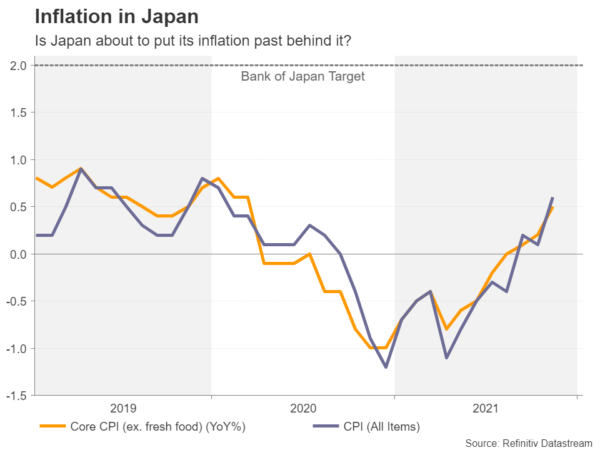

Policymakers in Japan have been striving for decades to boost inflation in the country but to no avail. Things may be about to change, however, as the pandemic and the ensuing health and economic policy responses have created a price shock that no one could have predicted at the onset. While Japan’s consumer price index currently stands at a paltry 0.6% year-on-year versus a staggering 7.0% in the United States, the inflation picture isn’t quite so subdued under the surface.

Businesses are facing mounting cost pressures as the global supply-chain bottlenecks and the surge in commodity prices is pushing up prices. Japan relies heavily on imports for its raw materials as well as for its energy needs so there is no escape from the changing global inflation landscape. Making matters worse is the yen’s depreciation against the US dollar; a weaker exchange rate makes imports more expensive.

In the past, Japanese firms have found it difficult to pass higher costs onto price-conscious consumers, but they may have no choice this time given the scale of the squeeze on their profit margins. Wholesale prices have already shot up to a record high of 9.0%. Inflation expectations among businesses and households are also on the rise, although they remain at low levels for now.

Will the BoJ sound the inflation alarm?

It shouldn’t come as much of a surprise therefore if the Bank of Japan ups its inflation projections in its latest outlook report on Tuesday. The bigger question for investors, though, is just how much more worried policymakers have become about inflation. Governor Haruhiko Kuroda has suggested that inflation could soon reach 2%. Yet, unless wage growth catches up, the comparatively modest spike in consumer prices won’t be seen as a risk to an economy that’s been mired in deflation since the 1990s.

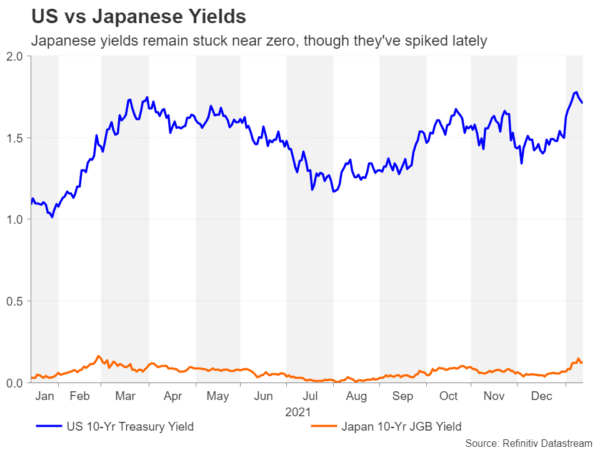

Money markets aren’t flagging a rate hike over the next year, although the odds are inching higher for 2023. However, a rate increase isn’t the BoJ’s only option. It might first decide to tweak its yield curve control policy by widening the target band on the 10-year Japanese government bond yield (currently 20 basis points above or below zero). Sovereign bond yields have been rallying lately as the major central banks pivot towards tighter policy so it’s quite probable the BoJ’s yield target could be tested should speculation heat up about higher rates in Japan too.

It may be too early to get less bearish about the yen

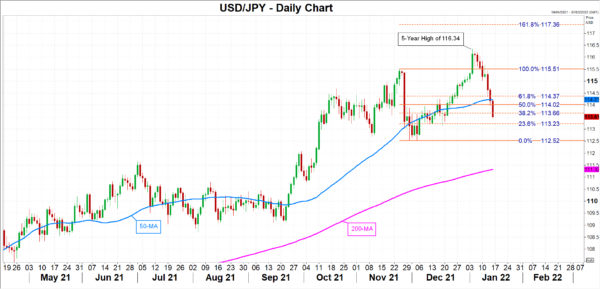

But such a shift in market expectations could be months away and, in the meantime, it’s still all about yield differentials due to other central banks’ actions as far as the yen is concerned. The Fed’s increasingly hawkish tone pushed the greenback to a five-year high of 116.14 yen earlier this month.

A correction is now in process, dragging the pair down to the 38.2% Fibonacci retracement of the November-December down leg at 113.66. A deepening of the correction could see the December trough of 112.28 yen being revisited. However, should the dollar perk up again, the next major target for the yen bears will be the 161.8% Fibonacci extension of 117.36.

To sum up, tighter policy seems some way off still in Japan. But with Japanese exports enjoying strong demand and the BoJ’s own surveys pointing to improved economic conditions, policymakers may not be so hesitant to respond to the rising threat of inflation. Reports suggest that discussions have already started on how the forward guidance on rates should be updated once inflation starts to approach 2%. The danger for the markets is that after such a long period of monetary easing in Japan, the timing of any change in the policy direction may catch them off guard.

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals