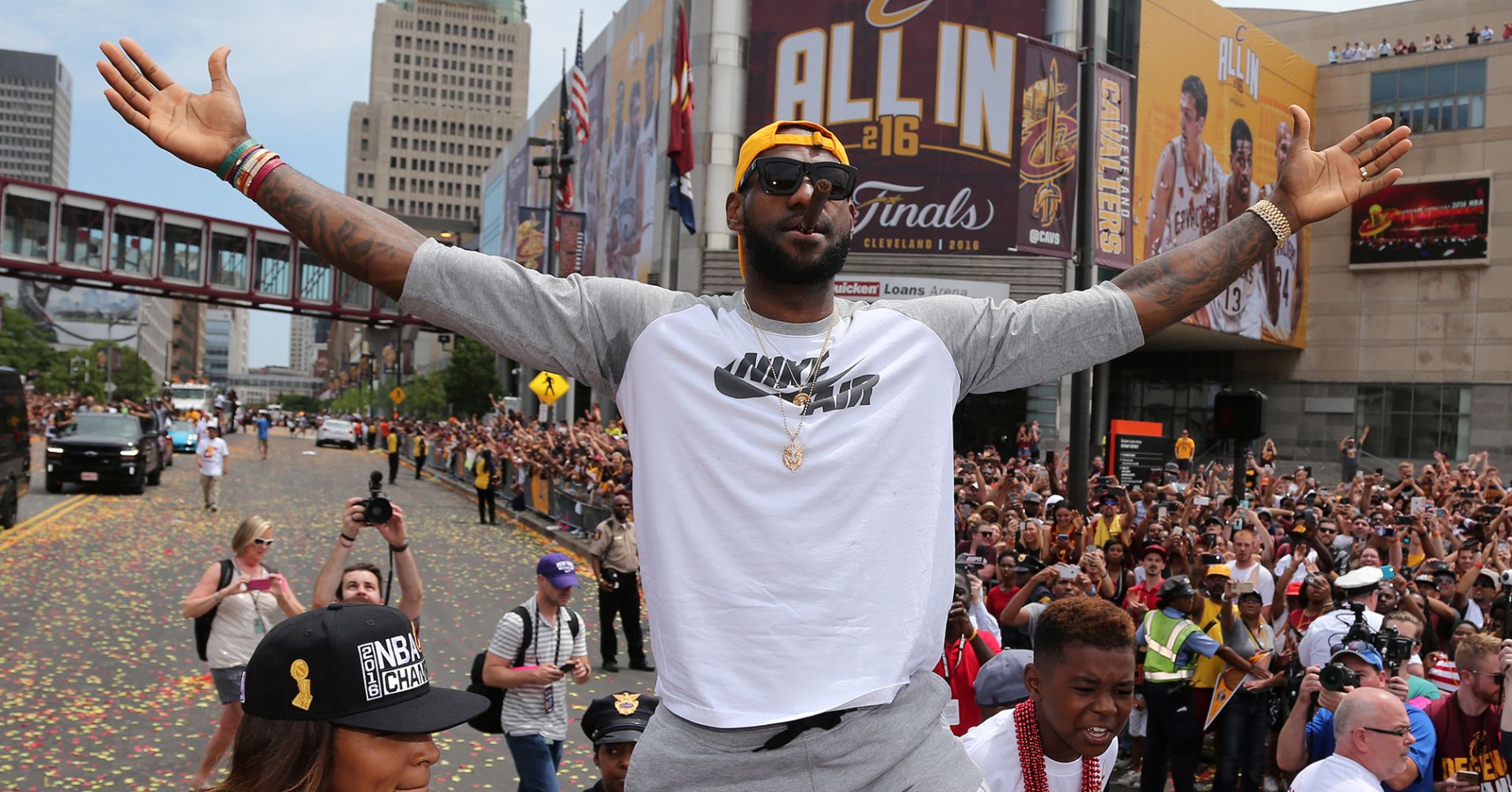

Cleveland has more than one reason to mourn LeBron James’ departure from the Cavaliers. While losing the four-time MVP could hurt its chances at another NBA trophy, it also could also dampen what’s currently a bustling economy around the Quicken Loans Arena.

James’ management group announced Sunday that the three-time NBA champion is signing a four-year, $154 million contract with the Los Angeles Lakers. The first-round NBA draft pick spent his first seven seasons in Cleveland, joined the Miami Heat in 2010 and made a dramatic return to Cleveland in 2014.

“No doubt [James] was a bright light to bring in people to the Q” said Jack Kleinhenz, regional economist at Kleinhenz & Associates and adjunct professor at Case Western Reserve University, using the arena’s nickname. “It will have a local effect but we’ll just have to work through it like we did the last time.”

Whichever city “King James” has played for has historically seen a boost in restaurants and bars opening within a mile of the NBA stadium, and when James leaves, the opposite takes place, according to a 2017 Harvard Kennedy School study.

During his time at the Cleveland Cavaliers and Miami Heat, the total number of bars and restaurants within a mile of those stadiums rose by an aggregate 13 percent, while total employment rose about 23.5 percent, the study found.

“Around the stadium, there are clear and direct local spillovers,” Stan Veuger, resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and co-author of the study told CNBC. “This is what you would expect when the Cavs become twice as good.”

When James played for Miami, there was a downward trend in the number of restaurants in Cleveland that coincided with an upward trend around the stadium in Miami. Likewise, when James returned to the Cavs, restaurants near Cleveland’s Quicken Loans Arena spiked while the number restaurants within a mile of the American Airlines Arena started to slide, according to the Harvard study.

For a city like Los Angeles, Veuger expects less of a James-related bump.

“It wouldn’t become the one big thing the city is known for,” he said. “The Los Angeles metro area is an order of magnitude bigger, so relative to the size of the economy, you’d see less of an impact locally.”

For attendance, though, Cleveland’s loss already seems like a gain for Los Angeles. In less than 24 hours after the announcement that James would be soon wearing a Lakers jersey, StubHub said visits to its Los Angeles Lakers tickets page increased by 1,831 percent compared with the daily average of the previous 30 days. Compared with the same date last year, traffic on the website was 7,398 percent higher.

Game attendance fell sharply the last time James announced his departure from Cleveland, which will have 41 regular season home games. Total attendance dropped 37 percent in the first two years James was gone from Cleveland, according to ESPN’s NBA Attendance Report. According to StubHub, four of its top five seasons for Cavaliers ticket sales were during James’s second stint on the team.

Average ticket prices also increased roughly 80 percent after James’ comeback, jumping to $107.90 from $60.03 the season before.

In 2016, the Cavaliers announced a $140 million project to renovate the downtown Quicken Loans Arena, known as the Q, which in part is being funded by a tax on ticket sales. The Cavs are extending their lease to 2034, and will pay $70 million and the balance being picked up by the county, a common practice in sports-arena financing.

Last year the arena generated $47 million in state and local tax revenue, $17 million in tax revenue for the city of Cleveland, and $6 million in tax revenue for Cuyahoga County, a spokesman for the Cavs said, citing data from CSL, a consultant in the convention, sports and leisure industry. It also generated $177 million in direct spending and supported 3,700 jobs, he said. The spokesman declined to provide details about 2018-19 season Cavs ticket sales.

Still, the venue hosts roughly 200 events per year, including the the Republican National Convention in July 2016.

“People from the greater Cleveland area go to Q and spend money,” said Andrew Zimbalist, economics professor at Smith College and former sports industry consultant. “There’s a substitution effect— that’s money they can now spend going to a local theater or Indians game.”

The real economic toll on Cleveland could be a loss of money from tourists traveling to see one of the best players in the league.

In 2015, Cleveland visitors spent $5.4 billion, with $1.3 billion in food and beverage sales alone, and recreation and entertainment brought in $1 billion, according to Destination Cleveland, the city’s tourism bureau. That total amount jumped roughly 10 percent from 2013, which a spokeswoman said is not necessarily tied to James’s return to the city’s team.

“The $100 million difference between 2013 and 2015 in recreation & entertainment spending would likely include some relationships to the Cavs as LeBron was back in Cleveland in 2015,” said Emily Lauer, a spokeswoman for Destination Cleveland, the city’s tourism and convention bureau. She said that the $100 million increase cannot be entirely attributed to James’s return, though.

Going forward, Cleveland will have to work harder to attract travelers to the city to fill its increasing number of hotel rooms.

Hotel data specialist STR count of hotel rooms has increased nearly 15 percent, to 24,141, since the end of 2013 through May 2018 and hotel. Those were in 206 hotels, up from 188 before James returned to the Cavaliers from Miami in 2014, and after the city hosted the Republican National Convention two years ago. Occupancy in those rooms fell 2.4 percent last year but is up 3.2 percent through May, according to STR.

More passengers have been flying to and from Cleveland Hopkins International Airport, too. The airport suffered from a decline in passenger traffic in 2014 after United Airlines stopped using the airport as a hub following its 2010 merger with Continental Airlines, but traffic has rebounded to more than 9.1 million passengers last year, the most since 2011, after U.S. and international airlines added service. Parking, concession revenue and aircraft landing fees generate revenue for airports.

James’s return to Cleveland also boosted the value of the Cavaliers franchise. Since he rejoined the team in 2014, its value has more than doubled, to $1.3 billion this year from $515 million, according to data from Forbes. The Cavs first topped the $1 billion mark in 2016, when it won its first — and only — NBA championship.

While plenty of factors go into the value of a sports franchise — one key is cash flow, which could be dampened if ticket sales slip with James’ departure.

“You look at a company’s’ valuation, it’s on the cash flow and to what extent it could be sold to somebody,” said Kleinhenz, who is also chief economist at the National Retail Federation. “Certainly, the attendance would be a factor.”

Despite James’s popularity, the city has other industries, like insurance, banking, technology and health care, including its crown jewel — the Cleveland Clinic.

Municipal bond analysts don’t appear too worried, for now.

Jane Ridley, a senior director at S&P Global Ratings said she is waiting to see whether there is an effect on the city’s revenue, but it won’t happen overnight. The agency has an investment grade rating on Cleveland’s general obligation debt, she said, adding that a decline in property tax revenue would likely have a bigger impact than James’s departure.

Moody’s Investor Service said the city’s stable A1 rating didn’t change when James returned to the Cavaliers in 2014 and that there’s not enough reason to change it upon James’s departure.

“Cleveland and Cuyahoga County both have diverse economies anchored by large employers which should largely mitigate any shock that perhaps their most marketable athlete leaving the city would create,” said Matthew Wong, director at Fitch Ratings. “Cleveland’s revenue growth will continue to trend lower than national inflation while Cuyahoga County’s revenue growth remains in line, neither of which will change dramatically with LeBron James leaving Cleveland.”

Mark Rosentraub, professor of sports management at University of Michigan, said that “you could see a small hit to the city of Cleveland, but it’s such a small number, most of the spending from basketball will be spent on other stuff.

“Cleveland is going to survive. Sports fans just might not be as happy.”

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals