For a rapidly growing share of older Americans, traditional ideas about life in retirement are being upended by a dismal reality: bankruptcy.

The signs of potential trouble — vanishing pensions, soaring medical expenses, inadequate savings — have been building for years. Now, new research sheds light on the scope of the problem: The rate of people 65 and older filing for bankruptcy is three times what it was in 1991, the study found, and the same group accounts for a far greater share of all filers.

Driving the surge, the study suggests, is a three-decade shift of financial risk from government and employers to individuals, who are bearing an ever-greater responsibility for their own financial well-being as the social safety net shrinks.

More from The New York Times:

Thinking about retirement? Consider working a little longer

Countdown to retirement: A five-year plan

Women outlive men. Why do they retire earlier?

The transfer has come in the form of, among other things, longer waits for full Social Security benefits, the replacement of employer-provided pensions with 401(k) savings plans and more out-of-pocket spending on health care. Declining incomes, whether in retirement or leading up to it, compound the challenge.

Cheryl Mcleod of Las Vegas filed for bankruptcy in January after struggling to keep up with her mortgage payments and other expenses. “I am 70, and I am working for less money than I ever did in my life,” she said. “This life stuff happens.”

As the study, from the Consumer Bankruptcy Project, explains, older people whose finances are precarious have few places to turn. “When the costs of aging are off-loaded onto a population that simply does not have access to adequate resources, something has to give,” the study says, “and older Americans turn to what little is left of the social safety net — bankruptcy court.”

“You can manage O.K. until there is a little stumble,” said Deborah Thorne, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Idaho and an author of the study. “It doesn’t even take a big thing.”

The forces at work affect many Americans, but older people are often less able to weather them, according to Professor Thorne and her colleagues in the study. Finding, and keeping, one job is hard enough for an older person. Taking on another to pay unexpected bills is almost unfathomable.

Bankruptcy can offer a fresh start for people who need one, but for older Americans it “is too little too late,” the study says. “By the time they file, their wealth has vanished and they simply do not have enough years to get back on their feet.”

The data gathered by the researchers is stark. From February 2013 to November 2016, there were 3.6 bankruptcy filers per 1,000 people 65 to 74; in 1991, there were 1.2.

Not only are more older people seeking relief through bankruptcy, but they also represent a widening slice of all filers: 12.2 percent of filers are now 65 or older, up from 2.1 percent in 1991.

The jump is so pronounced, the study says, that the aging of the baby boom generation cannot explain it.

Although the actual number of older people filing for bankruptcy was relatively small — about 100,000 a year during the period in question — the researchers said it signaled that there were many more people in financial distress.

“The people who show up in bankruptcy are always the tip of the iceberg,” said Robert M. Lawless, a law professor at the University of Illinois and another author of the study.

The next generation nearing retirement age is also filing for bankruptcy in greater numbers, and the average age of filers is rising, the study found.

Given the rate of increase, Professor Thorne said, “the only explanation that makes any sense are structural shifts.”

Ms. Mcleod said she had managed to get by for a while after separating from her husband several years ago. Eventually, though, she struggled to make ends meet on her income alone, and she fell behind on her mortgage payments.

She collects a small Social Security check and works at an adult day care center for people with intellectual disabilities and mental health problems. For $8.75 an hour, she makes sure clients participate in daily activities, calms them when they are irritated and tries to understand what they need when they have trouble expressing themselves.

“When I moved here from Los Angeles, I was wondering why all of these older people were working in convenience stores and fast-food restaurants,” she said. “It’s because they don’t make enough in retirement to support themselves.”

Ms. Mcleod said she hoped that filing for bankruptcy would help her catch up on her mortgage so she could stay in her home. “I am too old to move out of here,” she said. “I am trying to stay stable.”

The bankruptcy project is a long-running effort now led by Professor Thorne; Professor Lawless; Pamela Foohey, a law professor at Indiana University; and Katherine Porter, a law professor at the University of California, Irvine. The project — which is financed by their universities — collects and analyzes court records on a continuing basis and follows up with written questionnaires.

Their latest study —which was posted online on Sunday and has been submitted to an academic journal for peer review — is based on a sample of personal bankruptcy cases and questionnaires completed by 895 filers ages 19 to 92.

The questionnaire asked filers what led them to seek bankruptcy protection. Much like the broader population, people 65 and older usually cited multiple factors. About three in five said unmanageable medical expenses played a role. A little more than two-thirds cited a drop in income. Nearly three-quarters put some blame on hounding by debt collectors.

The study does not delve into those underlying factors, but separate data provides some insight. The median household led by someone 65 or older had liquid savings of $60,600 in 2016, according to the Employee Benefit Research Institute, whereas the bottom 25 percent of households had saved at most $3,260.

That doesn’t provide much of a financial cushion for a catastrophic health problem. Older Americans typically turn to Medicare to pay their medical bills. But gaps in coverage, high premiums and requirements that patients shoulder some costs force many lower-income beneficiaries to spend more of their own income on those bills, the Kaiser Family Foundation found.

By 2013, the average Medicare beneficiary’s out-of-pocket spending on health care consumed 41 percent of the average Social Security check, according to Kaiser, which also estimated that the figure would rise.

More people are also entering their later years carrying debt. For many of them, at least some of the debt is a mortgage — roughly 41 percent in 2016, compared with 21 percent in 1989, according to an Urban Institute analysis.

And those who are carrying debt into retirement are carrying more than members of earlier generations, an analysis by the Employee Benefit Research Institute found.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the lowest-income households led by individuals 55 or older carry the highest debt loads relative to their income. More than 13 percent of such households face debt payments that equal more than 40 percent of their income, nearly double the percentage of such families in 1991, the employee benefit institute found.

Older Americans’ finances are also being strained by the needs of those around them.

A little more than a third of the older filers who answered the researchers’ questionnaire said that helping others, like children or older parents, had contributed to their seeking bankruptcy protection. Marc Stern, a bankruptcy lawyer in Seattle, said he had seen the phenomenon again and again.

Some parents, Mr. Stern said, had co-signed loans for $10,000 or $20,000 for adult children and suddenly could no longer afford them. “When you are living on $2,000 a month and that includes Social Security — and you have rent and savings are minuscule — it is extremely difficult to recover from something like that,” he said.

Others had co-signed their children’s student loans. “I never saw parents with student loans 20 or 30 years ago,” Mr. Stern said.

“It is not uncommon to see student loans of $100,000,” he added. “Then, you see parents who have guaranteed some of these loans. They are no longer working, and they have these student loans that are difficult if not impossible to pay or discharge in bankruptcy, and these are the kids’ loans.”

Keith Morris, chief executive of Elder Law of Michigan, which runs a legal hotline for older adults, said the prospect of bankruptcy was a regular topic for his callers.

“They worked all of their lives, and did what they were supposed to do,” he said, “and through circumstances like a late-life divorce or a death of a spouse or having to raise grandkids, have put them in a situation where they are not able to make the bills.”

For Lawrence Sedita, a 74-year-old former carpenter now living in Las Vegas, the problems began when he lost his health insurance about two years ago. He said he had been on disability since 1991, when a double pack of 12-foot drywall fell on his head at work.

After his union, the New York City District Council of Carpenters, changed the eligibility requirements for his medical, dental and prescription drug insurance, he lost his coverage.

Mr. Sedita, who has Parkinson’s disease, said his medical expenses had risen exponentially. (A spokesman for the union declined to comment.)

A medication that helps reduce the shaking — a Parkinson’s symptom — rose to $1,100 every three months from $70, Mr. Sedita said. “I haven’t taken my medicine in three months since I can’t afford it,” he added.

He said he and his wife, who has cancer, filed for bankruptcy in June after living off their credit cards for a time. Their financial difficulty, he said, “has drained everything out of me.”

Doris Burke and Alain Delaquérière contributed research.

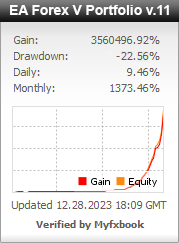

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals