US equity markets have been on a tear in 2019, reclaiming lost ground to come within breathing distance of their all-time highs. The rally has been fueled mainly by the Fed putting its rate-hike plans on ice, though easing trade tensions and corporate buybacks helped as well. While stocks could advance even further and break new highs, the risks seem increasingly asymmetric, with gains looking limited if growth stays solid but losses severe in case fears of a recession make a comeback.

What a difference a few months make. Back in December, the decade-long rally in US equity markets looked ready to end, with the major stock indices suffering heavy losses amid concerns that we are approaching the final stages of this business cycle, and that a recession may be around the corner. Fading fiscal stimulus from the tax cuts, overtightening by the Fed, trade tensions, a slowdown in the housing market, and global weakness from Europe to China were all part of this narrative.

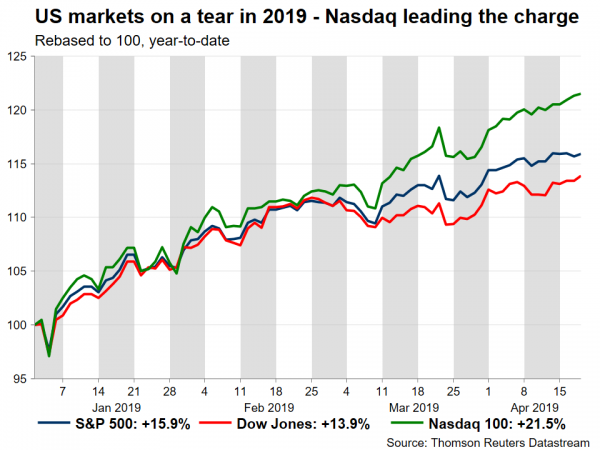

Fast forward to today. Fears of a recession have taken a back seat and US markets are flirting with their all-time highs, with the benchmark S&P 500 index gaining an astonishing 15.9% year-to-date.

What changed?

Fed to the rescue

In short, Fed policy changed. The US central bank made it clear it wouldn’t raise interest rates again for at least a few quarters while it monitors incoming data and the economy’s health. That was a sharp turn from the two rate hikes it had previously penciled in for 2019, which provided relief for stocks as lower borrowing costs tend to benefit risky assets.

In fact, market pricing has grown more pessimistic and currently indicates a ~50% probability for a Fed rate cut by December. This begs the question: if traders think there’s a good chance the most important central bank will cut rates soon in response to economic weakness, is the current equity rally sustainable?

Search for yield

It wasn’t just a cautious Fed that pushed investors towards riskier assets of course; signals of progress in the US-China trade negotiations no doubt helped. More broadly, one could argue that there’s no real alternative to stocks for now.

Bonds are particularly expensive, which means yields are low, providing very little or even negative real returns to investors when one accounts for inflation and currency hedging costs. Case in point, 5-year Greek government bonds now yield less than their US equivalents, which shows just how far the search for yield has gone.

Buybacks: Petal to the metal

Another major driver behind this rally has been the record pace of corporate stock buybacks. Companies buy their own stocks back from the market, decreasing the total number of stocks outstanding, and thus increasing the value of all remaining ones. By decreasing the supply of their stocks, they boost prices – providing immense support for markets.

The bad news is that this practice is coming under scrutiny by lawmakers, both Democratic and Republican ones. Prominent Democratic Senators want to ‘attach strings’ to buybacks, such as companies having to pay workers higher wages before buying their own stock. Republicans meanwhile suggest buybacks could be taxed at higher rates, to discourage them.

The bottom line is that any clampdown of buybacks would diminish one of the biggest sources of demand for equities – although this is extremely unlikely while Trump is in office.

Valuations – distorted?

Related to buybacks, is the more ‘attractive’ valuation of equity indices. Investors usually look at several metrics to determine whether a stock or index are ‘overvalued’ or ‘undervalued’. The most popular is the 12-month forward price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio. It represents the dollar amount someone needs to invest to receive back a single dollar in annual earnings, so the higher it is, the more expensive a stock is considered, and vice versa.

Equity index valuations are more reasonable now compared to recent years, when markets were trading at similar levels. However, the real question is whether these valuations have been ‘distorted’ by constant buybacks, which by definition boost earnings per share and thus push down on P/E ratios (as they leave fewer public shares to distribute earnings among). Hence, take metrics like P/E with a grain of salt, as they may be understating actual valuations.

Don’t discount “the Bern”

Markets haven’t focused on the 2020 presidential race yet, but that may change once the Democratic primary debates kick off in June. To be clear, the main risk for stocks is Bernie Sanders capturing the Democratic nomination. The senator from Vermont is an outspoken critic of large pharmaceutical firms, big banks, and huge multinationals overall. He wants to raise corporate taxes and increase social welfare, and while his policies may prove an effective antidote to low wage and productivity growth in the longer run, the short term effect on stocks will most likely be negative.

His bid shouldn’t be discounted for multiple reasons, not least because he is the frontrunner in opinion polls out of the Democrats that have entered the race, only behind former Vice President Joe Biden, who hasn’t announced yet. Separately, nearly all opinion polls have Sanders beating Trump if it gets to that, so it may be just a matter of time before investors realize how big of a risk “the Bern” is.

Recession ahead, or false alarm?

Finally, let’s examine the worst- and best-case scenarios ahead. On the pessimistic side, even though recession fears have abated given central bank caution, the likelihood for one remains elevated. In June, the US expansion will become the longest in history, so a downturn is already long overdue. Meanwhile, New York Fed models suggest a 27% chance – and rising – for a slump by early 2020. Notice that this number stayed below 50% even in the height of the 2008 crisis, so 27% may understate the actual probability. This would be a catastrophic outcome for stocks, with the potential for severe losses given current valuations, even if the recession is shallow.

On the bright side, the US economy is still in good shape, with the Atlanta Fed GDPNow model pointing to 2.8% growth in Q1. The global economy seems to be stabilizing too, thanks to massive stimulus in China. So in the optimistic scenario, where recession fears prove to be a false alarm, equities could eek out some further late-cycle gains and potentially carve out new record highs.

However, consider what that would mean for monetary policy. The Fed put its rate hike plans on ice because of growth worries, so if those truly diminish, then it could resume rate increases, which typically hurts stocks. That doesn’t necessarily mean markets will fall, especially in a strong growth environment – but rather that any upside could be limited amid rising interest rates.

Asymmetry

Concluding, the risks surrounding equity prices seem asymmetric. If fears of a recession prove correct, heavy losses could follow, but if the economy ‘dodges the bullet’ and the situation improves, any upside in stocks may be only limited as central banks resume their hiking cycles and cap the market rally.

Beyond that, demand for stocks hinges on corporate buybacks, valuations seem stretched, and even if growth remains stable and healthy, the mounting risk of higher corporate taxes via a Sanders presidency hasn’t been priced in – yet. Therefore, while markets could well advance and break new highs, the rally increasingly seems to be on wobbly legs, and the risk-to-reward of additional upside from here doesn’t look particularly attractive.

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals