U.S. Review

The Terrible Data (and the Stimulus) Start to Arrive

- Economic data from the early stages of the Great Shutdown have finally arrived, and they are as bad as feared. ‘Worst on record’ is about to become an all too common refrain in our commentary.

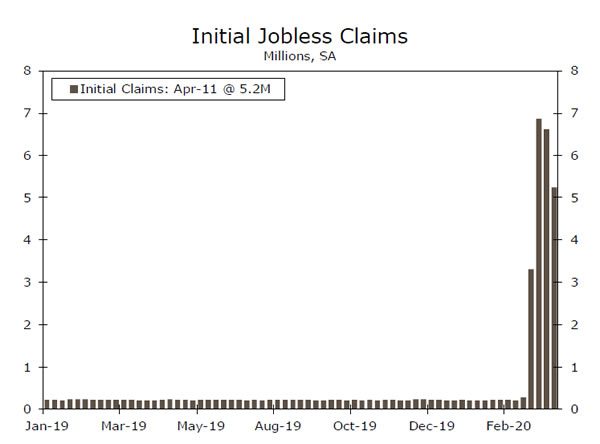

- 22 million people—or nearly 15% of the U.S. workforce—have filed for unemployment insurance in the past four weeks.

- Retail sales, industrial production and homebuilder confidence all posted historic declines, with the New York and Philly Fed indices pointing to even more pain in April.

- Household relief checks began to arrive, and the $349 billion of PPP loans were exhausted. We think a reload is likely.

The Terrible Data (and the Stimulus) Start to Arrive

Economic data from the early stages of the Great Shutdown have finally arrived, and they are as bad as feared. ‘Worst on record’ is about to become an all too common refrain in our commentary. Retail sales plunged 8.7% in March, as a 26% surge in grocery store sales (stockpiling of essential foods and toiletries that will not be repeated) was drowned out by historic declines in both durable (furniture -27%, autos -26%) and nondurable (clothing -50%, restaurants -27%) discretionary spending. Even this understates the decline in personal consumption, as retail sales don’t include hotel stays, airline or movie ticket sales, all of which fell to near zero by the middle of the month. This end of the quarter drop-off in activity means Q1 GDP growth will likely be mildly negative, but Q2 will be a disaster—we expect an annualized decline in excess of 20%.

The downside risk to our estimate is if layoffs continue to exceed expectations. In the past four weeks, 22 million people—or nearly 15% of the U.S. workforce—have filed for unemployment insurance. Layoffs in the directly affected industries have likely already peaked—a barber shop can’t close twice—but they are also likely picking up in non-directly affected industries as firms come to terms with the extent of the hit to aggregate demand and cut back on expansion plans. And while it is true services are being hit harder, manufacturing is getting pummeled too—industrial production fell 5.4% in March, the most since the United States demobilized after the Second World War. Meanwhile, the New York and Philly Fed indices point to the ISM manufacturing index falling to between 30 and 35. Even housing starts fell 22%, despite bustling activity in the first half of the month, while homebuilder confidence posted its largest one-month drop ever.

There was some relief this week—the $1,200 payments arrived for tens of millions of eligible Americans who have direct deposit information filed with the IRS. The roughly 70 million Americans who do not will need to wait for physical checks to arrive in the mail, all the while financial obligations continue to pile up. We are already seeing the result—only 69% of apartment tenants paid rent from April 1-5, compared to 82% in the same period last year, while the share of mortgage loans in forbearance leaped from 0.25% to 3.74%. Fortunately, those who have lost their job and successfully filed for unemployment insurance—a cohort totaling 12 million the week ended April 4—are receiving the additional $600 per week allocated by the CARES Act, which should do a respectable job plugging the sudden income hole in many households’ finances.

Small businesses have also tapped the fiscal spigot with gusto, already exhausting the $349 billion of Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans—convertible into grants if used for payroll or rent—by Thursday morning. The White House reportedly wants to reload with another $250 billion, but many, including us, feel this is insufficient. All told, we would not be surprised by a Phase 4 fiscal package of additional PPP loans, direct household payments and assistance to state & local governments.

Attention has now begun to shift to when the economy can ‘re-open.’ Well, the economy is not a light which you can switch on or off. Moreover, focus on who has the authority to open the economy—the White House or governors—is perhaps not relevant. The question is who has the ability. The answer is consumers, and businesses. Things will only get back to normal when people feel safe, and safety in turn depends on the public health response.

U.S. Outlook

Home Sales • Tuesday & Thursday

If there was any juice in the housing market in early March, it likely dried up by month’s end. Home sales had strong momentum headed into March. In the three months through February, single-family existing (about 90% of total) and total new home sales notched their strongest pace since late 2006. But, stay-at-home orders began popping up in the middle of March, and we wouldn’t be surprised if prospective buyers withdrew from the market even earlier amid the selloff in equity markets and to adhere to initial social-distancing guidelines. These assumptions are complemented by anecdotal reports from all over the country of sellers canceling open houses and buyers walking away from closings. The housing market is not at the center of the current economic storm, but the current environment certainly limits demand prospects; after all it is hard to visit a future home from the confines of your existing one. Home sales will fall as demand remains anemic for quite some time.

Previous: 5.77M; 765K Wells Fargo: 5.95M; 643K Consensus: 5.38M (Existing Sales); 650K (New Sales)

Durable Goods Orders • Friday

We expect a steep decline in March durable goods orders. Businesses likely grew cautious early in March and began to pare back spending even before lockdowns were officially put in place in the middle of the month. The new orders component of the widely followed ISM manufacturing survey fell to 42.2 in March, indicating the fastest pace of contraction in bookings since 2009. As seen by the chart to the left, the ISM orders component and core capital goods orders do not always move together from month-to-month, but follow a similar trend over time. What’s worse, March is likely just the beginning. Initial results from the regional Fed surveys suggest an even more pronounced drop off in April activity. The New York Fed’s new orders index fell to -66.3 in April, while the comparable measure from the Philly Fed’s survey hit -70.9—both firmly at record lows. Expect durable goods orders to struggle until confidence is restored and economic activity resurfaces.

Previous: 1.2% Wells Fargo: -8.0% Consensus: -11.1% (Month-over-Month)

Consumer Sentiment • Friday

Consumer sentiment nose-dived 18.1 points to 71.0 in the preliminary April report, marking the sharpest monthly decline on record. But sentiment still remained lofty compared to lows touched during the 2008 recession. Sentiment was dragged lower by perceptions of current conditions in April, and with over 20 million Americans filling for unemployment insurance in the past four weeks the only surprise here is that they didn’t fall further. More surprising was that expectations only receded to a level they stood at in 2014. We expect both to be revised lower in the final read due Friday. While we are nowhere near done with awful economic data, discussion shifted this week to when we can expect the economy to reopen. But even as stay-at-home orders are lifted, it will be consumer perceptions that drive the recovery, we will be paying particular attention to sentiment figures for any resurgence. Before that, however, they almost assuredly have more room to fall.

Previous: 71.0 Consensus: 69.0

Global Review

BoC Follows the Fed; Chinese Growth Nosedives

- The Bank of Canada met this week and adopted a series of market measures that mirrored the Federal Reserve’s efforts to dive into unexplored monetary policy territory to support the economy and financial markets.

- Data released last night showed real GDP in China declined 6.8% year-over-year in the first quarter, easily the biggest contraction since the country began reporting official figures in 1992.

- The Chinese data provided additional evidence that, unlike a typical recession, manufacturing is outperforming the consumer.

BoC Follows the Fed; Chinese Growth Nosedives

The Bank of Canada (BoC) met this week and adopted a series of market measures that mirrored the Federal Reserve’s efforts to dive into unexplored monetary policy territory to support the economy and financial markets. The BoC had already cut its policy rate to 0.25% and begun buying $5 billion in Government of Canada securities per week. In addition to these measures, the BoC announced that it will increase the level of these purchases, as well as launch a Provincial Bond Purchase Program of up to $50 billion. Also like the Fed, the BoC plans to begin buying up to $10 billion in investment grade corporate bonds, and will offer term repo funding of up to 24 months.

It is easy to see why the BoC has been equally as aggressive as the Federal Reserve. Between COVID-19 and historically low oil prices, the Canadian economy has been particularly hard hit. The March employment data showed total employment declining by slightly more than one million, a historic decline that would equate to roughly eight million jobs lost in the United States when adjusting for the different sizes of the labor forces in two economies. Although the Canadian dollar has strengthened a bit off its recent lows, it has still depreciated against the U.S. dollar by nearly 9% in 2020. Our currency strategists expect some additional near-term weakness in the Canadian dollar vis-à-vis the U.S. dollar, with only moderate recovery in 2021.

Data released last night showed real GDP in China declining 6.8% year-over-year, easily the biggest contraction since the country began reporting official figures in 1992. The Chinese data provided additional evidence that, unlike a typical recession, manufacturing is outperforming the consumer in most parts of the world. Retail sales declined 19% year-over-year in Q1, while industrial production contracted by 8% over the same period. And in March specifically, industrial production fell just 1.1% yearover- year, while retail sales were still down nearly 16% compared to the same month last year. By category, the decline in retail sales in March was as one might expect. Restaurant and catering spending was down 47% year-over-year, clothing spending declined 35% and household electronics sales fell 30%.

Given the timeline of COVID-19’s spread in China compared to other major economies, real GDP growth in China in Q2 will almost certainly be much stronger than it will be in the United States or the Eurozone. But, the path ahead for the Chinese economy will still be difficult. The still sluggish pace of retail sales in March suggests a combination of consumer behavior changes and a material loss in disposable income. Indeed, per capita real disposable income fell 3.9% year-over-year in Q1.

And while the factory sector may bounce back more quickly, the collapse in global aggregate demand will weigh on Chinese exports. More fiscal and monetary stimulus is likely on the way in China, and specifics will be debated at a meeting of the Communist Party’s Politburo in the days ahead. Our expectation remains that real GDP in China will decline 1.2% in 2020, its first annual contraction in decades.

Global Outlook

South Korea Q1 GDP • Wednesday

After China, South Korea and Italy were at the forefront of the next wave of COVID-19 spread. Case growth in South Korea ramped up in February, and the total number of new daily cases peaked on March 3 at 851. Since then, reported cases have declined significantly, with reported daily new cases below 100 every day since April 1. The earlier peak and subsequent decline in South Korea create the conditions for which its data may be useful as a leading indicator for economic outcomes in other economies, such as the United States and the Eurozone. South Korea managed to avoid some of the strictest lockdown measures put in place in other countries, and its economy is more reliant on manufacturing output, so its March data may prove to be a bit stronger than the April data in the United States and Europe. That said, any leading indicator is a useful tool in today’s uncertain times, and we will be watching South Korea’s GDP print next week closely.

Previous: 1.3% Consensus: -1.5% (Quarter-over-Quarter, Not Annualized)

U.K. Retail Sales • Thursday

The United Kingdom began widespread lockdowns around the same time as many places in the United States, with public places like restaurants and bars closing on March 20, and even stricter national limitations put in place a few days later. Thus, the March retail sales data to be released next Thursday will likely be a bit like the U.S. were this past week: historically bad, but with the worst still to come.

Manufacturing and service sector PMI readings for April are also due next week, as is consumer price inflation data for March. Broadly speaking, our expectations for these data in the U.K. are similar to what we look for in the United States and the Eurozone. We anticipate a further decline in both service sector and manufacturing activity, and for inflation to slow going forward, led by the significant decline in global energy prices. Our expectation is that real GDP in 2020 will contract more in the U.K. than it will in the U.S. but less than in the Eurozone.

Previous: -0.5% Consensus: -2.8% (Ex. Fuel, Month-over-Month)

Eurozone PMIs • Thursday

The preliminary readings for the Eurozone manufacturing and service sector PMIs could offer the first look at where the economic data will bottom out in areas of the world that have seen severe outbreaks. COVID-19 case growth appears to have slowed significantly across most parts of Europe, and many countries are starting to lay the groundwork for a gradual lifting of restrictions in May. The March PMIs were disastrous, with the service sector in particular contracting at a much faster pace than the depths of the Great Recession.

At the eye of the storm is Italy, which reported a stunningly low 17.4 services PMI in March. If there has been any silver lining in the economic data in Europe, it is that the manufacturing sector, which was the laggard of the two pre-COVID-19, has not yet seen a more significant deterioration. Italian data for Q1 real GDP growth will be reported on April 30, a few days before April PMI data.

Previous: 44.5 and 26.4 Consensus: 38.0 and 24.5 (Manufacturing and Services)

Point of View

Interest Rate Watch

Progress Toward a New Therapy

While this week certainly had its share of bad news, with huge declines in retail sales, industrial production and manufacturing activity in the Northeast, the week ended on some promising news surrounding therapeutics to treat COVID-19, encouraging progress on vaccine development and a coherent and credible course to ease the lockdowns implemented to slow the spread of the virus. Bonds yields took their cue from this week’s weaker reports on retail sales and industrial production. Retail sales plunged 8.7% but the key “control group” category of sales that ties back to real GDP growth came in relatively solid, rising 1.7%. The increase takes out much of the downside risks to Q1 GDP growth, which should come in close to our -1.2% estimate. The 5.4% drop in industrial production was unsurprising. Factory output fell a larger 6.3%, as assembly lines abruptly shut and workers stayed home. The steep drops in the New York and Philly Fed surveys was eyepopping but expectations rose in both.

Thursday’s news from Gilead and promising results from Moderna, Roche, Johnson & Johnson and a host of other companies have bolstered hopes that meaningful progress is being made on therapeutics to mitigate symptoms of COVID-19 and develop vaccines to vanquish it. The better news on the medical front closely preceded President Trump’s plan to re-open the economy. The plan calls for gradually restarting economic activity in coordination with state and local political and business leaders. Boeing also announced they will begin to restart aircraft assemblies at its Everett Washington assembly plant. The sudden combination of good news helped rally stocks going into Friday morning. If it holds through the day, this may mark a shift in the risk paradigm and bottom for bond yields. There has been a great deal of healing in the financial markets. Quick and decisive actions by the Federal Reserve helped restore order to the Treasury market and brought needed liquidity to the high-yield and investment grade corporate markets as well as the municipal market. While we are not out of the woods yet, the Fed appears to have the upper hand at preventing the healthcare and economic crisis from morphing into a financial crisis, which would be much more difficult to extricate ourselves from. Even if this is the bottom for Treasury yields, they are not destined to take off but rather rise gradually, presaging actual improvements in economic growth.

Credit Market Insights

Strained Small Businesses

On Thursday, the Small Business Administration (SBA) announced that its $349 billion Payroll Protection Program (PPP) had run out of funds. While we believe this program will eventually be replenished in the next round of fiscal stimulus, the 1.6 million loans, which will turn into grants if used primarily to maintain payroll, doled out over the past two weeks underscore the precariousness of small businesses’ present financial situation. Small businesses— defined as firms with fewer than 500 employees—play an important role in the U.S. economy, accounting for roughly 40% of nonfarm payrolls, and providing relief to these businesses will be an important step in avoiding a more prolonged downturn. Keeping these businesses afloat will be no easy task, however, not least because many small firms were facing financial strain even before COVID-19 hit the United States. Late last year, with an expanding economy and strong labor market, more than a quarter of small businesses were distressed or at-risk, according to the Federal Reserve’s 2020 Small Business Credit Survey. In response to a then hypothetical question, only one in seven small businesses owners said they could continue normal operation in the face of a two-month revenue loss, while two thirds of small business owners indicated they would have to cut salaries or lay off workers. The unprecedented speed and breadth of the current economic downturn suggests that the reality is likely worse than the hypothetical situation respondents were considering only a few months ago.

Topic of the Week

Another ‘Service’ Industry That’s Under Duress

The CARES Act instructs mortgage servicers to grant forbearance to a wide swath of borrowers, which should alleviate household financial stress but may in turn stress the housing finance system. The rationale for the program is simple—many homeowners are out of work through no fault of their own and therefore should have leeway to meet their fixed expenses.

While the concept is straightforward—a temporary stoppage of financial obligations—execution is a bit more complicated. Typically, banks extend credit to a homebuyer, but then sell that mortgage to another firm which restructures the incoming payments, packages them into mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and sells the MBS to investors. This process generally frees up bank balance sheets, encourages more lending and makes homeownership more affordable. Mortgage servicers are the middlemen—between the homeowner and the MBS investor—who collect and then distribute payments. While the extension of forbearance mitigates the threat of one risk—widespread delinquencies—it raises another. Specifically, the CARES Act instructs servicers of federally backed mortgages (about 70% of all mortgages) to grant forbearance of up to 180 days or more to borrowers who are experiencing financial hardship due to COVID-19, either directly or indirectly. The potential problem is that while homeowners can delay their payments (top chart), servicers are still expected to pay MBS holders, leading to a cash crunch.

Because agency MBS are backed by the U.S. government, the servicers of these mortgages are ultimately protected if homeowners default, but the avalanche of forbearance requests in such a short period of time threatens their liquidity. Many servicers are nonbanks (around 40% of mortgages backed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are serviced by nonbanks) and therefore do not have as robust funding sources as banks. In this way, the shortterm liquidity crunch brought about by the deluge of forbearance could choke off credit creation (bottom chart) and make it more difficult for housing to help lead the recovery. We would expect further government action—either a broad Fed liquidity facility or more targeted programs via the Treasury or housing finance regulatory agencies—to prevent this from happening.

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals