Economic numbers are confirming the atrocious-looking decline in economic activity in April – the first full month of social/physical distancing restrictions in a wide swath of advanced economies, including Canada and the US. Yet, as the extent of damage to the economy becomes apparent, focus is shifting to what the recovery will look like. To be clear, the scale of the economic collapse over March and April would have been almost unimaginable just a couple of short months ago. Canadian employment declined by 3 million in the past two months – including the 2 million drop reported in April that was actually a substantial upside surprise relative to market expectations. The United States shed 20.5 million positions in April. In both cases, the job declines since February have been multiples of total cumulative job losses in the 2008/09 recession.

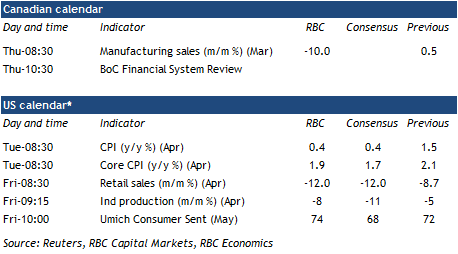

But that bad news was largely expected. And some early green shoots have started to appear in activity indicators. Business confidence showed signs of improvement in Canada late in April, as did our own tracking of credit card purchases. The spread of COVID-19 has eased and regions are beginning to ease restrictions, or at least release plans to do so in the not too distant future. Odds have increased that April will mark the low-point of the downturn in Canada and the long-road to recovery can begin in May. The prospect of improving (or at least less-bad) activity going forward should take some of the shock out of backward-looking economic reports. We expect Canadian manufacturing sales to plunge 10% in March, led by a sharp drop in auto output as factories closed up over the back end of the month. Those numbers will likely get worse in April before starting to grind back higher in May. In the US, retail sales are expected to have plunged by double-digits in April.

Economic data for March/April will tell us where the economy has been – the Bank of Canada’s now annual Financial System Review could offer more important clues about where it’s going. Household debt vulnerabilities have been elevated for years in Canada. Concern has lingered that even a relatively mild economic shock could escalate into a broader and longer-lasting household deleveraging cycle similar to that seen in the United States following the 2008/09 recession. The economic shock we have now seen over the last two months has been anything but mild, but the government policy response has also been unprecedented. To be sure, households will struggle under the weight of unprecedented job losses, but we also expect the range of novel government income support measures to provide meaningful offset, particularly at the lower end of the wage scale where job losses have been concentrated. On broader financial conditions, the Bank of Canada is likely to take comfort from the fact that the wide swath of programs (including asset purchases) to pump liquidity into markets over recent weeks/months have been working – credit spreads that spiked higher earlier in the crisis have eased lower. With central banks here and abroad lining up to use essentially limitless funds to support financial markets, the risk of the economic shock turning into another financial crisis has clearly eased.

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals