Executive Summary

Earlier this year, the Federal Reserve rose to the challenge of a global pandemic and restored order and liquidity to rattled financial markets through rates cuts, asset purchase programs, and a comprehensive program of credit and liquidity facilities to breathe life into the economy. The fight against the virus has had a few bad rounds in recent weeks, however. After a run of better-than-expected economic data, there is a pervading sense that the hot-streak is poised for interruption amid increasing COVID-19 cases that have led many states to pause or, in some cases, roll back, reopening plans.

Fed policymakers have become resigned to that reality and have cautioned that recent improvements in economic data, particularly rosy job gains, may be fleeting. “A thick fog of uncertainty still surrounds us, and downside risks predominate” is how Fed Governor Lael Brainard put it in a speech earlier this month. Those comments followed similar downbeat remarks from other Fed speakers including Richmond Fed President Thomas Barkin, who warned that unemployment could rise again as employers come to grips with a recession that may be longer than first anticipated. But the steady drumbeat of commentary will abate as we have now entered the blackout period for the July 29 meeting, the period during which Fed policymakers refrain from public comment just prior to a scheduled meeting.

The primary takeaway from the June 10 Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting was a pledge by the committee to do “whatever it takes” to help revive the U.S. economy. Despite handwringing about the impending fallout from increased case counts in recent weeks, the economic data remain decent, at least so far. Consequently, a formal rollout of forward guidance, which we discuss in more detail subsequently, would be premature for the July 29 FOMC meeting, in our view. That said, once its formal strategy review, which has been underway for about a year, is complete and the fog has lifted on the economic data, we do expect the FOMC to adopt some form of explicit forward guidance, if not at its September 16 meeting (the last prior to the elections) then at its November 5 meeting.

Yield curve control (YCC) is another idea that is seriously under consideration, though we also doubt it will be implemented at this meeting. Still, the merits of YCC have been touted by various Fed speakers in recent weeks and, as we describe in this report, it has had some desirable policy outcomes in economies where it has been tried, including a slower expansion of the central bank’s balance sheet.

Will the FOMC Re-adopt Some Form of “Forward Guidance”?

“Forward guidance” is a tool that the FOMC can use to alter the expectations of households and businesses. By committing, either explicitly or implicitly, to a future path for the fed funds rate, the committee can influence longer-term interest rates and thereby current spending decisions by households and businesses. For example, a commitment to refrain from monetary tightening for an extended period of time can put downward pressure on the 10-year Treasury yield, on which most long-term mortgage rates are based. Lower mortgage rates can boost new home sales and housing starts.

Forward guidance can take a few forms. First, the FOMC can commit to a future path for the fed funds rate over some time horizon, and the FOMC initially adopted this approach in the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis. In December 2008, when the committee slashed the fed funds rate from 1.00% to a target range of 0.00% to 0.25%, the FOMC also noted that “weak economic conditions are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels of the federal funds rate for some time.” The committee eventually became more specific in August 2011 when it said that low rates likely would be appropriate “at least through mid-2013.” At subsequent meetings, the FOMC eventually extended its time-based forward guidance to “at least through late 2014” and then to “at least through mid-2015.”

Forward guidance can also take the form of some threshold-based outcome, such as the unemployment rate or the rate of inflation. This is the approach the FOMC adopted in December 2012 when it said that low rates would be appropriate “at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6-½ percent, inflation between one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the Committee’s 2 percent longer-run goal, and longer-term inflation expectations continue to be well anchored.” But as the unemployment rate approached 6-½ percent without a noticeable rise in inflation, the FOMC changed its threshold for the unemployment rate to “below” 6-½ percent. The committee eventually dropped its reference to the unemployment rate.

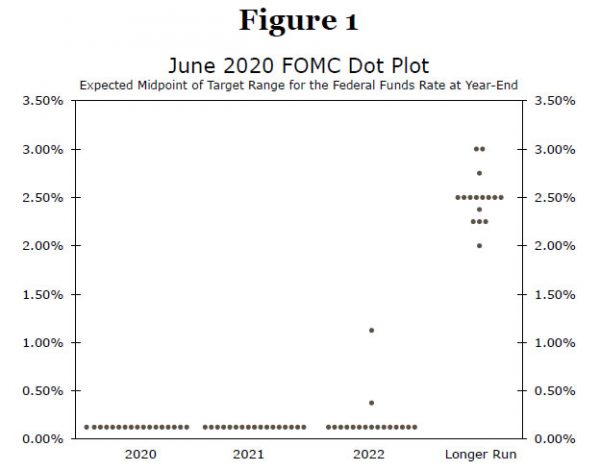

Finally, there is a third form of forward guidance that is a bit more implicit than the explicit forms of time-based or threshold-based guidance. That is, committee members give their individual assessments on a quarterly basis of “appropriate monetary policy” via the “dot plot.” As shown in Figure 1, all 17 committee members thought at the time of the June FOMC meeting that it would be appropriate to keep the target range for the fed funds rate between 0.00% and 0.25% through the end of 2021. Fifteen committee members thought that it would be appropriate to keep rates on hold through the end of 2022.

The FOMC considers forward guidance to be part of its monetary policy “toolkit” because it can help to depress long-term interest rates. In that regard, the yield on the 10-year Treasury security generally remained below 3% from 2012 through 2015. But as the preceding discussion also makes clear, forward guidance, whether time-based or threshold-based, can be confusing to market participants if the goalposts keep moving. Therefore, long-term interest rates may not decline as much if market participants are not clear about the Fed’s intentions.

The minutes of the June 29 FOMC meeting revealed that “most” committee members thought that the FOMC “should communicate a more explicit form of forward guidance for the path of the federal funds rate…as more information about the trajectory of the economy becomes available.” But the minutes also reminded readers that the Federal Reserve is currently undertaking a review of its monetary policy strategy and tactics, and that “many” committee members thought that the completed review “would help clarify further how the Committee intends to conduct monetary policy going forward.” Previous statements by Fed officials suggest that the review will be completed by the end of the summer.

In our view, the committee likely will not adopt an explicit form of forward guidance at the July 29 FOMC meeting. Not only is the “trajectory” of the economy still highly uncertain at this time, but we question whether the Fed has completed its strategy review yet. That said, we look for the FOMC to adopt some form of explicit forward guidance at its September 16 meeting or, at the latest, its scheduled meeting on November 5.

What Are the Different Kinds of Yield Curve Control?

Over the past few months, speculation has continued to build that the Federal Reserve could eventually adopt a yield curve control (YCC) policy. But what exactly is yield curve control? At its most simple level, YCC is a policy whereby a central bank explicitly caps or targets yields at one or more spots along the country’s sovereign bond yield curve. At a more granular level, YCC can take many forms, a few of which we discuss below.

The United States actually has historical experience with YCC. During World War II, the Federal Reserve capped yields more or less across the entire Treasury curve to keep the federal government’s borrowing costs low and stable during the war.1 By mid-1942, the Treasury yield curve was fixed for the duration of the war, anchored at the front end with a 0.375% T-bill rate and a 2.5% long-bond rate. In order to enforce this policy, the Fed bought along the curve as necessary in order to maintain the fixed rates. Accordingly, Treasury indebtedness increased from $58 billion at year-end 1941 to $276 billion at year-end 1945 (a 375% increase), but the Fed’s System Open Market Account went from $2.25 billion to $24.3 billion (a 980% increase) over the same period. These purchases helped ensure the level and shape of the yield curve remained in line with the Fed’s desired targets.

More recently, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) adopted a YCC policy in September 2016. The BoJ began targeting the yield on 10-year governments bonds at “around zero percent”, which was close to the prevailing rate at the time. Initially there was a fluctuation band of +/- 10 bps, but this was widened to +/- 20 bps in July 2018. In March 2020, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) adopted its own YCC policy, targeting a 3-year government bond yield of 0.25%.

At the most recent FOMC meeting, participants discussed these three experiences and weighed the pros and cons of various YCC approaches. The main benefit of any YCC policy is somewhat obvious; by explicitly putting a target on sovereign bond yields and promising to purchase bonds as necessary to meet this objective, the Federal Reserve can control interest rates in a much more complete way than it can by setting the fed funds rate or purchasing a fixed dollar amounts of bonds. Put another way, in “regular” quantitative easing, the Fed sets the amount of bonds it will buy but allows the price of the bond to float. In YCC, the Fed sets the price, and allows the amount of bonds it buys to fluctuate. With such a firm grip on the yield curve, the Fed can drive interest rates lower across the entire curve, or at least prevent them from rising much.

But which of these three options would the FOMC be most likely to choose, should it go down this rabbit hole? As a first point, the committee still appears to be at least somewhat wary of YCC policies. According to the June meeting minutes, “nearly all participants” indicated that they had many questions regarding the costs and benefits of YCC policies in the United States. As such, we doubt the FOMC will adopt a YCC policy of any sort at its upcoming July meeting.

But the discussion is likely to continue at the upcoming meeting, and the RBA approach strikes us as the most likely to garner further discussion. The FOMC signaled as much in the June minutes, noting that “among the three episodes discussed in the staff presentation, participants generally saw the Australian experience as most relevant for current circumstances in the United States.” WWII-style YCC strikes us as highly unlikely anytime soon, with the BoJ approach only marginally more likely. Capping yields at the longer-end of the curve would potentially provide more accommodation, but how much lower could these yields really go? During WWII, it was easier to maintain a solidly upward sloping yield curve given the higher level of absolute yields that prevailed at the time. And more recently in Japan, the BoJ adopted a negative policy rate, in part to help keep the curve upward sloping. If the Fed is unwilling to go negative, something we believe is true at this point in time, the 10-year yield could only fall about 25 bps before the Treasury curve would be roughly as flat as it is in Japan. A Treasury curve that was this flat for an extended period of time could cause challenges, particularly for bank profitability, with only limited benefits from the relatively small decline in yields.

Furthermore, this approach is essentially an explicit backstop of fiscal policy, as the Fed agrees to keep both short- and longer-dated yields capped regardless of how much the federal government borrows. Participants at the June meeting expressed concerns about this, saying that “under yield curve targeting policies, monetary policy goals might come in conflict with public debt management goals, which could pose risks to the independence of the central bank.” Indeed, even after WWII ended, it took the Fed six years before an accord was reached with the Treasury that allowed the central bank to stop explicitly backstopping federal borrowing. Other FOMC participants expressed concern about inadvertently setting yields caps at “inappropriate levels”, since longer-term yields are determined by difficult-to-know factors such as longer-run inflation expectations and the longer-run neutral real interest rate.

The major advantage of the RBA model is that, to some extent, it is just an extension of forward guidance. As discussed earlier, the Fed has already signaled through the dot plot that the median projection among FOMC participants does not include a rate hike through 2022, or two-and-a-half years from now. Capping yields at the intermediate part of the curve, such as at the 3-year point, would help reinforce this message. Markets are already priced for the federal funds rate to remain at zero through the medium term (Figure 2), but a YCC policy through the intermediate part of the curve could help prevent those expectations from changing prematurely, as occurred during the “taper tantrum” in mid-2013.

Additionally, another benefit of YCC policies in both Australia and Japan is that, by adopting an explicit target, the respective central banks have generally not needed to engage in sizable purchases to maintain the target. The central banks’ credible commitments are enough to keep the market priced at the targets without needing aggressive intervention. The BoJ’s sovereign bond purchases slowed considerably after YCC was adopted (Figure 3). In Australia, the RBA has barely purchased any government bonds after its initial round of purchases a few months ago. Compare those experiences to the present situation in the United States, where the Federal Reserve is purchasing $80 billion per month in Treasury securities indefinitely, despite the fact that yields remain largely unchanged over the past few months.

What if, by adopting a YCC control policy, the Fed could keep yields at their current levels, without having to continue to expand its balance sheet? Fed Governor Brainard hinted at this possibility in a recent speech, suggesting that “there may come a time when it is helpful to reinforce the credibility of forward guidance and lessen the burden on the balance sheet with the addition of targets on the short-to-medium end of the yield curve.” Thus, we will be looking for clues at the July 29 press conference and in the subsequent minutes of the meeting that the FOMC is more explicitly considering a YCC policy along the lines of the one adopted in Australia.

1 For further reading, see Garbade, K.D. (February 2020). “Managing the Treasury Yield Curve in the 1940s.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports.

Chaurushiya, R. & Kuttner, K. (June 2003). “Targeting the Yield Curve: The Experience of the Federal Reserve, 1942-51.” FOMC Memo.

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals