It’s been a roller-coaster year for the commodity-linked dollars of Canada, Australia and New Zealand as the global pandemic has wreaked havoc on international trade and on commodity prices – the lifelines of the three economies. But as countries around the world make progress towards recovering from the once-in-a-generation crisis, Australia and New Zealand seem poised to bounce back the quickest. Canada’s recovery may be slightly shakier due to its over dependency on the United States and oil exports. But overall, the three currencies have similar fundamentals driving them higher, although their paths may diverge somewhat over the coming year.

A stronger finish to 2020

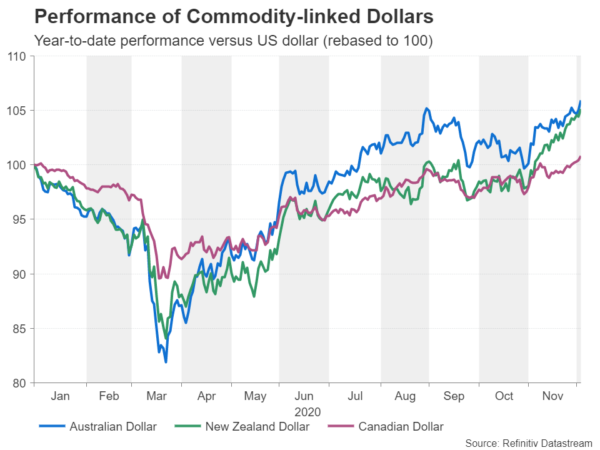

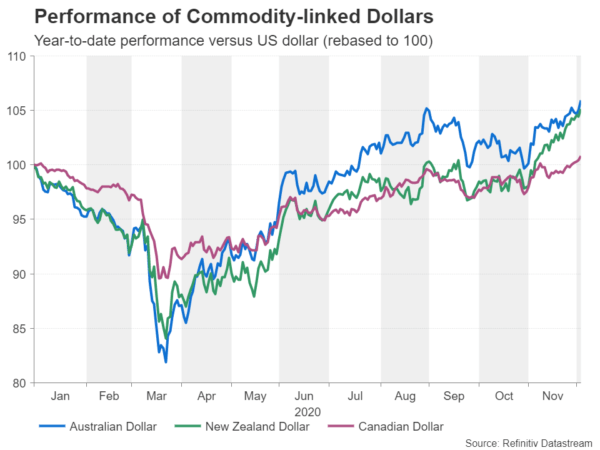

Having already started the year on a trade war-induced downtrend, the aussie, kiwi and loonie took a deep dive at the height of the Covid-19 market turmoil in March. But since then, they’ve been on a steady path upwards. The aussie is up about 6% in the year-to-date against the US dollar, the kiwi is up nearly 5%, and some way behind is the loonie, which has gained just over 1%.

Strikingly, their rallies have been shaped by three phases. The first boost was in late March from the coordinated fiscal and monetary response globally. Then it was the worldwide easing of the lockdown restrictions in early June that gave rise to hopes of a V-shaped recovery. The latest bout of euphoria was sparked from the vaccine breakthrough in November that shone light at the end of the pandemic tunnel.

However, most of the positive news about a vaccine as well as expectations for additional monetary and fiscal stimulus have been more or less priced in by now. So how much further can the risk rally run?

It’s all looking up Down Under

For the Australian dollar, there’s plenty that could push the currency well beyond current peaks. Australia trades heavily with Asia, where the recovery is gathering pace and is less influenced by the spiralling virus cases in Europe and America, which are seeing their rebounds lose steam. Having effectively gotten its second wave under control early on, Australia is now able to loosen many of its restrictions.

Moreover, metal and ore prices, such as those of iron ore, coal and copper, are soaring, boosting the country’s terms of trade. Resources comprise the bulk of Australia’s exports, which, incidentally, are primarily destined for Asia.

RBA and China tensions may cap aussie upside

However, even with the demise of the Trump administration, the trade outlook is not risk-free. Relations between Beijing and Canberra have soured very significantly in recent months to the extent that China has imposed hefty tariffs on Australian wine, barley and beef. So far, China has steered clear from slapping duties on resources imports, which are crucial for its domestic industries, and so the economic impact on Australia has been minimal. But tensions may flare up further in 2021 if US President-elect Joe Biden decides to form an anti-China alliance and Australia opts in. If China’s tariffs spread to Australia’s mining exports, the market reaction would almost definitely not be as benign as it’s been to date.

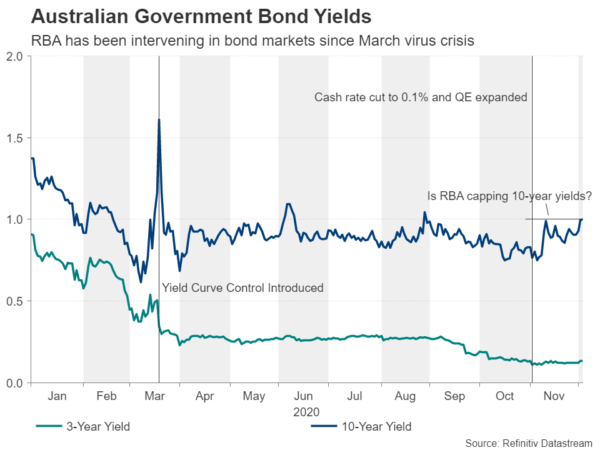

But a bigger threat to the aussie’s uptrend is the Reserve Bank of Australia. At its November meeting, the RBA extended its quantitative easing (QE) programme by allocating A$100 billion to specifically target 5- to 10-year government bonds, having previously targeted only 3-year bonds. Whilst the aggressive expansion of QE was in response to the bumpy recovery, many see the move as indirect currency intervention. The RBA appears to be unofficially capping the 10-year yield at around 1% and this may pose a growing challenge for the aussie’s advances going forward, especially if the US 10-year Treasury yield were to overtake it.

Negative rates priced out for RBNZ

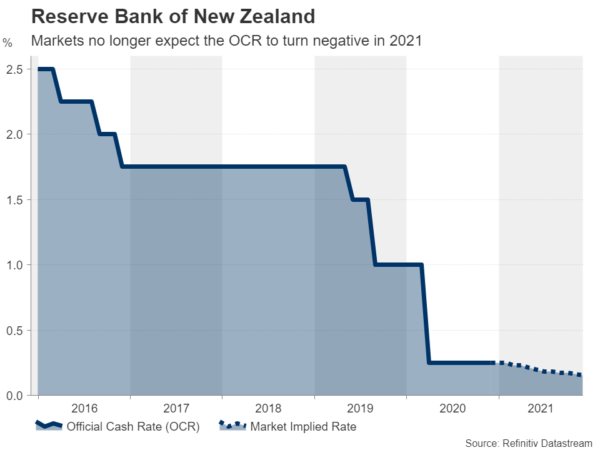

Not to be outdone, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand is engaged in aggressive QE of its own. However, at its last meeting, the RBNZ climbed down from its more pessimistic forecasts. Like Australia, New Zealand has one of the better records for its handling of the coronavirus outbreak, and despite a second lockdown, the recovery is now on a more solid footing. The stronger-than-anticipated turnaround in economic conditions prompted the RBNZ to revise up its growth forecasts for next year, inadvertently leading investors to completely price out expectations of negative interest rates in futures markets.

There was a further blow for negative rates last month when the country’s finance minister raised the prospect of adding house prices to the RBNZ’s mandate to prevent property bubbles. Given the present boom in the housing market, such a decision would kill off any chance of negative rates being introduced in the foreseeable future.

Will the RBNZ allow kiwi bulls to run wild?

The New Zealand dollar has surged by 6% in November alone on the back of the shifting rate expectations, with the fast-improving outlook and vaccine optimism further bolstering the currency. Looking ahead into 2021, one potential risk to consider is the possibility that vaccines are rolled out more slowly than hoped. This could delay how soon New Zealand would be able to lift its travel restrictions, and in turn, push back the full reopening of the economy.

Another danger for the kiwi is that the RBNZ may not tolerate a steep appreciation in the exchange rate for much longer. Although policymakers have yet to sound particularly alarmed about the kiwi’s ascent, their tolerance level may change if the rally gets even wilder.

Loonie still trailing behind

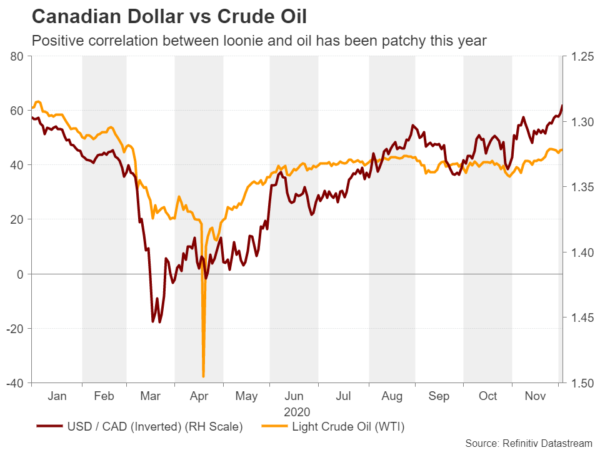

The Canadian dollar has been playing catch-up over the past month as the end of the US election uncertainty combined with the vaccine success have injected a new lease of life into the stalled rally. Higher oil prices have provided an additional lift as investors have turned bullish about the demand outlook as an end to the pandemic comes within sight. Crude oil is Canada’s primary export so a further rebound in oil prices would bode well for the North American economy.

However, US risks have not totally dissipated as the recovery south of Canada’s border could run into trouble if Congress does not renew two key unemployment benefits that will expire at the end of December. America is Canada’s biggest trading partner by a mile so a faltering recovery would have strong ripple effects across the region as well as globally. Another challenge for the Canadian economy is getting through the winter months while it battles an escalating second wave.

Nevertheless, with both headwinds potentially clearing early next year, the loonie’s gains may yet accelerate and the Bank of Canada won’t get in its way. Out of all the major central banks, the Bank of Canada has been the least dovish during the pandemic and is the least likely to pump more stimulus in the coming months. Hence, if the risk-on theme continues, the loonie could be in a position to outperform its aussie and kiwi peers in 2021 after consistently lagging them this year.

Can the US dollar make a comeback?

As valid as the domestic fundamentals are in support of each currency’s uptrend, there is, as always, another dimension to consider in the world of forex and that is the outlook for the US dollar. It is no coincidence that the aussie, kiwi and loonie are simultaneously scaling multi-year peaks just as the greenback is on a broad retreat.

The US currency is likely to weaken even more over the course of next year, as apart from traders unwinding their safe-haven positions and buying riskier assets amid the brightening economic backdrop, real yields for US Treasuries are falling and are set to decline further. Inflation in the United States has not fallen dramatically like it has done in some other countries from the shutdowns, and with the Federal Reserve recently adopting a more ‘flexible’ inflation targeting regime, expectations for future inflation are also ticking up.

Should real yields continue to come under pressure, it’s hard to see how the dollar can reverse course anytime soon, though much will depend on what the Fed signals at its next meeting on December 15-16 when it will likely provide an updated forward guidance.

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals