U.S. Highlights

- Without much noteworthy economic data this week, market sentiment soured on a leaked Biden administration proposal to raise the maximum tax rate on capital gains of high-income taxpayers.

- First quarter GDP data and a rate announcement from the Federal Reserve are also on the docket next week. Growth in the first half of this year is coming in faster than we expected, raising the risk of earlier Fed hikes.

Canadian Highlights

- The federal government’s latest budget showed persistent deficits to extend pandemic supports and increase spending on a wide range of social investments including a new national daycare program.

- The Bank of Canada upgraded its growth outlook, scaled back its bond-purchase program, and moved-forward its expectation for when economic conditions would warrant a higher policy rate.

Global Highlights

- An increase in shipping costs and shortages of key manufacturing inputs have reminded us of the vulnerabilities of relying too much on efficient rather than resilient supply chains.

- Supply-side bottlenecks are likely to increase cost-push inflation in the near-term. While shortening supply chains will make businesses less vulnerable, it could also push up prices in the medium to long-term.

U.S. – Big Events Next Week Drive Markets

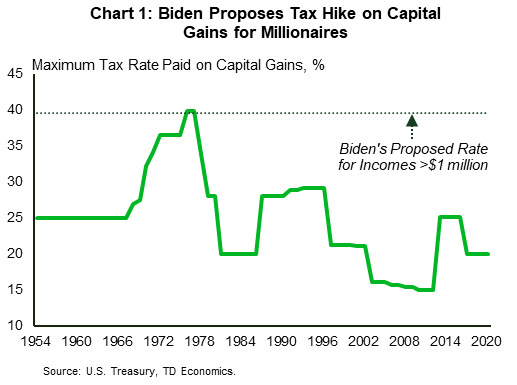

Without much noteworthy economic data this week, market sentiment took its cue from policy announcements that are expected next week from the Biden administration. Sentiment seemingly soured on the news that the spending under the American Families Plan will be funded by tax hikes on higher income taxpayers. President Biden had outlined his intention to raise taxes on higher incomes in his campaign platform. Particularly relevant for investors is the proposal to tax capital gains at 39.6% (up from 20%) for people with incomes above $1 million, which would be the same rate as the top marginal rate on income under Biden’s proposals (Chart 1). That would match the late 1970s, the highest rate historically, however, Bloomberg estimates this would only affect about 0.3% of the population.

These changes need to be passed by Congress, and so will either require Republican support or budget reconciliation. The latter is more likely, and therefore the support of moderate Dems, like Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema, may mean tax hikes could be watered down before they are passed. The White House is still finalizing the details of its plan. The key spending items will likely include funding for platform promises like: paid family leave, child care, universal pre-K and free community college.

There is also some big economic news coming next week: first quarter GDP and a Federal Reserve interest rate announcement. We expect economic growth to accelerate to a 6% annualized pace in Q1, up from 4.3% in Q4 (Chart 2). This acceleration will be largely due to jump up in consumer spending – from 2.3% in Q4 to 10% in Q1. The second wave of Covid-19 infections and associated restrictions had held back spending at the end of 2020, but fiscal stimulus that has come in two waves over the course of Q1 has boosted spending. Recall eligible Americans received $600 payments back in January, and a further $1400 in late March. We have seen in retail sales and high-frequency data that consumers haven’t hesitated to spend these windfalls.

Personal income and spending details for March will also be released on Friday, which will tell us a lot about momentum heading into Q2. We expect it to be healthy. Overall, growth in the first half of the year is tracking better than we expected in March, and on its own is enough to raise 2021 real GDP growth forecast from 5.7% to 6.2%.

This upgrade to economic growth raises the risk the Fed will hike rates sooner than we expected in March. So we will be listening very closely to how Chair Powell talks about the outlook on Wednesday. This is not a meeting with a summary of economic projections but shifts in messaging will be closely parsed. We will be publishing Dollars and Sense next week – so stay tuned for our updated view on the Federal Reserve.

Canada – Ottawa’s Ambitious Budget

Two years in the making, the federal government’s hotly anticipated budget outlined how the government would spend the $100 billion it promised in the Fall Economic Statement. Nearly half of that new spending is booked for the upcoming fiscal year, much of which will go toward extending pandemic supports to workers and businesses. Additional deficit spending over the next fiscal year amounts to roughly 2% of GDP, suggesting upside risk to economic growth forecasts for 2021 and 2022.

Beyond pandemic measures, the government casts a wide net in terms of planned investments, pledging support for low-wage workers, students, indigenous communities, seniors and small and medium sized businesses. Meanwhile, some $17.6 billion is put towards investments in the green economy. The marquee measure, however, is the announcement of a new national daycare program, which will cost $30 billion over six years as it is set up and carry an ongoing cost of $9 billion annually thereafter. The government estimates by raising the labor force participation rate, affordable childcare could boost real GDP by as much as 1.2% over the next two decades. As an analogue, since the introduction of its subsidized daycare system in 1997, Quebec’s labour force participation rate has climbed by about three percentage points.

Achieving the government’s relatively rosy longer-term growth projections will require these productivity enhancements to come to fruition. And only with healthy economic growth will the debt-to-GDP ratio, which is forecast to sit around 50% in the next five years, remain at that level. While obviously much higher than just over 30% where it was before the pandemic, this is below levels seen during the 1990s fiscal crisis. And, despite higher debt levels, low interest rates are expected to keep debt service charges at historically low levels (Chart 1).

Despite publishing their updated forecast after the budget was released, the Bank of Canada had to build in fiscal assumptions before having seen it. The Bank assumed $85 billion in additional deficit spending in their forecast accompanying this week’s interest rate decision. The Bank is now projecting much stronger overall growth over the projection horizon compared to their January outlook, driven by higher commodity prices, continued fiscal and monetary support, a quicker vaccine rollout, and the economy’s greater resilience to the pandemic (Chart 2). This is also supporting their decision to scale back on their bond purchasing program by $1 billion per week.

This resilience also implies less scarring on the economy from the pandemic. Alongside expectations of stronger investment, this has spurred an upgrade to the Bank’s assessment of potential GDP growth. All in, the Bank now expects economic slack to be absorbed in the second half of 2022, instead of sometime in 2023 as in their prior projection. While this would imply an earlier liftoff for rates, Governor Macklem made sure to emphasize the uncertainty around the projection and that policymakers would be patient in ensuring that slack is absorbed.

Global – Supply Chain Disruptions Are Harbingers of the Future

The pandemic has laid bare the vulnerabilities of relying too much on efficient rather than resilient supply chains. Rising shipping costs and shortages of key manufacturing inputs have once again reminded us of the fragility of the global trading system.

For context, lets start with developments in 2020. In the first half of last year, thousands of empty shipping containers were left stranded on European and American shores due to lockdowns. In the second half of 2020, European and American demand for Asian-made goods rebounded. This led to a sharp rise in freight rates. Why? Because too much money was chasing too few containers! In fact, the cost of shipping between China and Europe hit a record high late last year on the back of recovery in consumer demand and container shortages.

Fast forward to 2021. The Suez canal incident further exacerbated container shortages. The canal’s blockage prevented its usage by other cargo ships, some of which were forced to take longer and costlier detours. This delayed the arrival of containers at their destinations and contributed to a temporary increase in shipping costs which are already more than three times the level a year ago (Chart 1). The Suez Canal carries over 10% of global trade. The six-day incident held up almost $60 billion ($9.6 billion each day) of global trade. The long-term trade impact of these disruptions is likely to be small given that the global trade in goods amounts to roughly $18 trillion a year. However, the delays will have a domino effect, which will reverberate across global supply chains for months to come.

To make matters worse, a recovery in global demand has contributed to a shortage of microchips and semiconductors. A blaze in one of the world’s leading auto chip makers in Japan and an uncharacteristically cold winter in southern U.S. added fuel to the fire. A drought in Taiwan further threatens to slowdown chip production since large quantities of water are used in the process. If that wasn’t enough, U.S.-China tensions and concerns of a prolonged shortage have pushed Chinese companies to stockpile supplies. These developments have been especially problematic for the auto industry, which had already slashed production due to a semiconductor shortage. It doesn’t stop there. A global chip shortage has also hampered production of other durables such as home appliances and computers.

As a result, businesses are faced with high supplier delivery times and low inventories. Consumer demand is likely to jump as restrictions are eased, but logistical bottlenecks will keep a lid on supply. This could further increase costs for businesses. What this means for consumer price inflation depends on how much of the increase in costs is passed on. Businesses have two options:

- Pass on all or part of the increase in input costs to consumers. This approach would increase (cost-push) inflation. But businesses are faced with a trade-off. Such an approach could prompt consumers to switch demand to other businesses who don’t pass on the costs to consumers.

- Businesses absorb the increase in costs. This approach would lower business profits but have little to no impact on inflation. The upside to this approach is that consumer demand for goods produced by businesses that absorb costs will remain stable. It may even increase, depending on how much of their excess savings households unleash.

The impact of supply chain disruptions will also be felt in the medium to long-term. Businesses are already reshoring and shortening their supply chains. This makes them less vulnerable to future supply chain disruptions. But it would also reduce their access to cheaper inputs from other parts of the world. It would also entail higher costs for consumers. Exporters would also become less competitive as they would have to rely on more expensive domestic inputs rather than cheaper foreign inputs.

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals