Part IV: Conclusions

Summary

- Monetary systems have evolved over centuries, and there is nothing inherently “permanent” about the current system, which is composed of “public” money (i.e., paper bills that are the liabilities of central banks) and “private” money (i.e., bank deposits that are the liabilities of private enterprises).

- In our view, cryptocurrencies with high price volatility and inelastic supplies (e.g., Bitcoin and Ether) likely will continue to represent an important investment class, but they are ill-suited as a form of money.

- Likewise, privately-issued stablecoins, at least as currently constructed, are also ill-suited as a form of money due to their potential susceptibility to “runs.”

- Many major central banks are actively weighing the benefits and drawbacks of issuing their own central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). The Federal Reserve has essentially handed the decision about potential issuance of a U.S. CBDC to lawmakers.

- Determining exactly what Congress will eventually authorize, if indeed it actually does, is more or less impossible. But a scenario in which Congress chooses not to authorize a U.S. CBDC does not seem implausible to us. We could envision a scenario in which lawmakers require that private stablecoin issuers become insured and regulated depository institutions. Under such a scenario, the line between stablecoin issuers and commercial banks would become increasingly blurred.

- Due to the benefits of digitization, it is only a matter of time before some form of digital currency takes its place among the primary methods through which payments are made, in our view.

NOT A DEPOSIT. NOT PROTECTED BY SIPC. NOT FDIC INSURED. NOT GUARANTEED. MAY LOSE VALUE. NOT INSURED BY ANY FEDERAL GOVERNMENTAL AGENCY

This commentary is provided for information purposes only and does not contain any recommendations or investment advice. The Firm makes no recommendation as to the suitability of investing in digital assets, including cryptocurrencies. Investments in digital assets carry significant risks, including the possible loss of the principal amount invested. It is only for individuals with a high risk tolerance who can withstand the volatility of the digital asset market. Investors should obtain advice from their own tax, financial, legal and other advisors, and only make investment decisions on the basis of the investor’s own objectives, experience and resources.

The Form of Money Continues to Evolve

We began this four-part series on digital currencies by describing in Part I how exchange has evolved over the centuries. Initially, exchange took place by barter, but humans eventually invented “money,” because it is a more efficient form of exchange than barter. Forms of money with intrinsic value, such as cowrie shells and precious metals, eventually gave way to paper money. Today, the monetary system of most economies is composed of risk-free “public” money (i.e., paper bills that are the liabilities of central banks) and “private” money (i.e., bank deposits that are the liabilities of private enterprises).

Individuals and businesses in most economies willingly accept private money as a perfect substitute for risk-free public money, because the value of bank deposits is guaranteed, at least up to some limit. Furthermore, the supervisory and regulatory framework that exists in most economies gives the public some confidence that the banking system is financially sound. In short, money today is “backed” by trust. Individuals accept paper bills and checks as means of payment for goods and services, because they trust that other people will in turn accept those forms of money as payment. If that trust breaks down, then so too does the monetary system.

Pros and Cons of Digital Currencies as a Form of Money

There are no features of the current monetary system that necessarily make it the final stop in the evolution of money. In that regard, cryptocurrencies, which exist in electronic form only, have come into use as a medium of exchange in recent years. Moreover, the explosive growth in digital currencies, which did not even exist prior to 2009, is a testament to some of their qualities that make them a better medium of exchange than paper money.1 Among other benefits, which we discussed in more detail in Part I, is the speed of payment. Rather than waiting for the “check to clear,” settlement in digital currencies occurs essentially instantaneously.

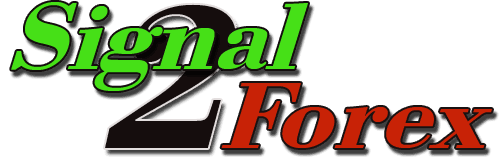

But one of the most notable drawbacks to some cryptocurrencies is their extreme price volatility. For example, the price of Bitcoin has dropped roughly 35% on balance since its peak in November, and daily changes of 10% are not uncommon (Figure 1). This volatility derives from the limited supply of many cryptocurrencies. Prices can fluctuate widely as demand shifts back and forth along an inelastic supply curve. Due to this high degree of price volatility, many cryptocurrencies are not good “stores of value,” at least not over short periods of time. Furthermore, the limited supply of these digital currencies could potentially lead to price deflation of goods and services.

There is a class of digital currencies, known as “stablecoins,” which we discussed in more detail in Part II that tend to have stable values. Therefore, stablecoins would be a better form of money than cryptocurrencies that have higher degrees of price volatility. In addition, the supply of stablecoins can expand elastically as demand increases. The potential deflationary situation that is associated with inelastically supplied cryptocurrencies does not arise with stablecoins.

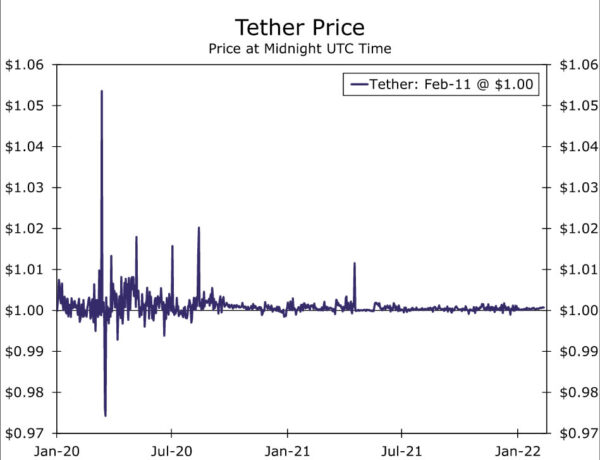

However, the major drawback to privately-issued stablecoins is their potential susceptibility to “runs.” Stablecoin issuers hold assets that they can use to meet redemptions. In addition to bank deposits and risk-free Treasury bills, the assets of stablecoin issuers often include higher-yielding commercial paper. The values of stablecoins are generally stable. But because stablecoins are the liabilities of private enterprises that are not guaranteed, their prices can decline when owners of the tokens start to question the value of the issuer’s assets. For example, the price of Tether, one of the most highly traded stablecoins, weakened noticeably in March 2020 when financial market volatility spiked (Figure 2). In short, privately-issued stablecoins can be subjected to runs, much like commercial banks were prior to the establishment of deposit insurance and credible supervisory and regulatory agencies. If runs on stablecoin issuers were to become systemic, then financial stress could potentially become extreme. In other words, trust, which is the only quality that “backs” money today, could break down.

As noted earlier, currency is a risk-free asset for the public, because it is a liability of the central bank. But there are some drawbacks to currency, which we discussed in more detail in Part III. Specifically, currency is not an efficient way to make large value payments or payments that need to be made remotely. These problems could be solved if central banks could create their own digital currencies. These so-called central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) could also offer some benefits in the form of monetary policy options. But there are many complex design issues involved with CBDCs that require careful consideration. For example, CBDCs would be risk-free assets of individuals and businesses that hold them. If the public perceives CBDCs to be superior to the liabilities of commercial banks, then disintermediation from the banking system could occur, which potentially could have negative consequences for economic growth.

Therefore, many central banks are proceeding cautiously with the introduction of digital currencies. Among major central banks, only the People’s Bank of China has issued a CBDC to date. The Swedish Riksbank has tested a prototype and the European Central Bank plans to have its own prototype ready for testing in 2023, although neither central bank has yet to commit to actual issuance. The Federal Reserve is conducting in-depth research about the pros and cons of its own digital currency, but it has essentially handed the decision about potential issuance of a U.S. CBDC to lawmakers.

What Does the Future Hold for Digital Currencies?

So, what does the future hold? For starters, digital currencies have established a firm foothold in the global financial system, and they are simply not going away, in our view. But we believe that cryptocurrencies with inelastic supplies and significant price volatility (e.g., Bitcoin and Ether) will play a limited role as a form of money. Money has three functions: it is a medium of exchange, a unit of account and a store of value. Digital currencies such as Bitcoin and Ether are currently being used as a medium of exchange, but only to a limited extent. Rather, the vast majority of transactions today continue to be made in national currencies (e.g., U.S. dollars, euros, etc.) Their use as a unit of account is also quite limited at present. That is, prices of most goods and services continue to be denominated in national currencies, not in terms of specific cryptocurrencies.

Prices of many cryptocurrencies with inelastic supplies have risen significantly on balance since their introduction, but their price volatility does not make them good stores of value, at least not over short-run horizons. Consequently, most individuals and corporate treasurers likely would not want to make this class of cryptocurrencies a significant part of their liquid cash balances. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no issuance to date of securities (i.e., stocks and bonds) that are denominated in inelastically supplied cryptocurrencies. Securities continue to be denominated in national currencies such as U.S. dollars, euros, Japanese yen, etc. As long as prices of these inelastically supplied cryptocurrencies remain highly volatile, we think that corporate treasurers will largely refrain from issuing securities that are denominated in them. Therefore, individuals who want to invest in this class of cryptocurrencies are largely limited to owning just the digital currency, rather than an interest-earning or dividend-paying security.

In our view, cryptocurrencies with inelastic supplies and highly volatile prices will continue to offer investment opportunities for individuals and institutions, especially those with high tolerances for risk. In that regard, this class of cryptocurrencies likely will represent an important investment class, similar to emerging market securities. Although these cryptocurrencies are not currently regulated, they potentially could fall under the regulatory purview of an agency such as the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). We will defer to investment professionals regarding issues of investment options and potential regulation. But we do not see cryptocurrencies with inelastic supplies and high price volatility replacing national currencies as the primary mediums of exchange and units of account anytime soon.

The class of digital currencies that are known as stablecoins have some advantages over their more volatile counterparts in terms of a form of money. In addition to the property of instantaneous payment, a quality that is inherent of all digital currencies, stablecoins generally have stable values and elastic supplies. But as noted previously, the main drawback to stablecoins is that they are liabilities of private enterprises that are not guaranteed, at least not at the present time. Their potential susceptibility to runs could add to volatility during periods of financial stress.

Furthermore, there is the issue of “convertibility” among stablecoins. Assume that Individual A, who has a Tether account, needs to pay Individual B, who has an account that is denominated in USD Coin. One of the individuals could exchange one stablecoin for the other, but there would be transaction costs associated with the exchange. These transaction costs do not arise when individuals are making and receiving payments in the same national currency (e.g., U.S. dollars). Because of their potential susceptibility to runs and this convertibility issue, we do not envision the replacement of national currencies with privately-issued stablecoins, as currently constructed, anytime soon.

Central banks could potentially begin to issue their national currency by digital means rather than via paper bills. Large and remote payments, which are problematic for paper currencies, could be made easily with CBDCs. But a notable drawback to CBDCs is that they could lead to disintermediation from the commercial banking system, if ill-designed. Furthermore, most central banks simply do not have the scale or the scope to onboard and maintain the accounts of millions of households and businesses, a task that currently is being handled by commercial banks in each individual economy. Many major central banks are actively considering the pros and cons of digital currencies, but none to date, aside from the Peoples Bank of China, have begun to issue their own CBDC.

Due to the benefits of digitization, it is only a matter of time before some form of digital currency takes its place among the primary methods through which payments are made, in our view. But we also believe that there will be some public element to payment-related digital currencies due to the drawbacks of privately-issued stablecoins that were noted previously. The exact design of these digital currencies will ultimately depend on the legal, regulatory and political milieus of each economy that adopts one. In the United States, the Federal Reserve has highlighted four basic principles to which any U.S. CBDC would need to adhere: privacy protection, intermediated (i.e., offered via the private sector), transferable and identity-verified. However, the Federal Reserve has also said that “it does not intend to proceed with issuance of a CBDC without clear support from the executive branch and from Congress, ideally in the form of specific authorizing law.”

Determining exactly what Congress will eventually authorize, if indeed it actually does, is essentially impossible. But a scenario in which Congress chooses not to authorize a U.S. CBDC does not seem implausible to us. There already is some skepticism in Congress regarding CBDCs. For example, Representative Tom Emmer (R-MN) recently introduced a bill that would amend the Federal Reserve Act to prohibit the Fed from issuing “a central bank digital currency directly to an individual.” Of course, Emmer is just one voice in Congress, but the political economy of the country seems to skew toward private sector solutions to many issues, including those that are related to the financial sector.

So, if Congress does not authorize a U.S. CBDC, how could it allow the country to capture the benefits of payment digitization? The report that was published in November 2021 by the President’s Working Group on Financial Markets (PWG) offers a potential way forward. As we noted in Part II, the PWG report concluded that Congress should pass legislation requiring stablecoin issuers to become “insured depository institutions, which are subject to appropriate supervision and regulation.” Deposit insurance in conjunction with a robust supervisory and regulatory framework should largely prevent “runs” on stablecoin issuers, much as bank runs have become exceedingly rare since the creation of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) in 1933.

If Congress were to follow the PWG recommendation, then stablecoin issuers would start to resemble commercial banks, which currently issue private money in the form of bank deposits. Legislation could be crafted such that these stablecoin enterprises would need to hold some proportion of their privately-owned deposits as reserves at the Federal Reserve, much as commercial banks do today. Commercial banks in turn could also begin to issue their own digital forms of private money, with the blessing of the regulatory authorities. Over time, the lines between stablecoin issuers and commercial banks would become increasingly blurred. The government would continue to delegate the task of issuing most of the nation’s money supply to the private sector, with appropriate regulatory and supervisory oversight, including robust capital requirements. The private sector would be able to drive innovation in payment technologies, as it does today.

Under this scenario, the potential for disintermediation of the banking system would largely disappear, because the United States would not have a CBDC. Likewise, the potential of runs on stablecoin issuers would also become largely irrelevant, because they would be insured and regulated enterprises. But what about the issue of “convertibility”? Similar to the current environment, in which numerous stablecoins exist, a specific bank/stablecoin issuer presumably would be issuing its own form of digital currency, while another platform would be issuing a different form of digital currency. Would these two currencies be easily and inexpensively convertible?

The Federal Reserve noted in its report that “transferability” is one of the qualities a CBDC should have. That is, a CBDC “would need to be readily transferable between customers of different intermediaries.” Although this quality is meant to apply to any digital currency that the Fed would issue, it could equally apply to digital currencies that are issued via the banking system. Any legislation that requires stablecoin issuers to become insured depository institutions could also include the requirement that their tokens are readily transferable between different depository institutions.

But even if legislation did not specify this requirement, we think competitive pressures would eventually force the stablecoins of different private sector issuers to largely resemble each other. U.S. dollars that are held in one commercial bank today are identical to U.S. dollars held in another commercial bank. Moreover, an individual can send payments of U.S. dollars to another individual without transaction costs. So, we think depository institutions/stablecoin issuers would all eventually issue the same U.S. dollar-based digital currency.

Conclusion

Starting with Bitcoin’s inception in 2009 to today, the number of digital currencies in circulation has exploded from one to more than 17,500, which have an aggregate value of roughly $2 trillion at present. Although the exact future of digital currencies is difficult to discern, one thing seems certain to us: they are here to stay. There is nothing inherently “permanent” about the current form of money, and digital currencies have many superior qualities to paper money.

But there are different types of digital currencies, and some are better suited for some purposes than others. There is a class of digital currencies that generally have inelastic supplies with high degrees of price volatility. Notable examples are Bitcoin and Ether. In our view, digital currencies with these characteristics are ill-suited to serve as a form of money, and we do not envision them replacing national currencies as the primary mediums of exchange and units of account anytime soon. But they could represent a class of investment assets that, although unregulated at present, may eventually fall under some regulatory purview. But we will defer to the opinions of investment professional on these matters.

There is another class of digital currencies, which are known as stablecoins, that tend to have stable values and elastic supplies. But they are the liabilities of private enterprises and their values are not insured, which makes them potentially susceptible to runs. Therefore, we do not envision them replacing national currencies, at least not as they are currently constructed. That said, stablecoins have more promise than inelastically supplied digital currencies as potential forms of money, if some changes are implemented.

Much will depend on the decisions that governments make regarding CBDCs. If a government decides to move ahead with a CBDC, then the future of privately-issued stablecoins would likely be more tenuous. Everything else equal, why would the public want to use the liabilities of a private enterprise as a form of money when it could use a risk-free digital currency that is supplied by the central bank? But stablecoins could still have a future depending on the underlying design features of the CBDC. Outside of China, actual issuance of CBDCs, if it occurs at all, still seems to be a few years in the future in most economies.

Will the United States ever have a CBDC? It obviously is difficult to know with certainty, but we are skeptical. The Federal Reserve does not intend to move forward with issuance “without clear support from the executive branch and from Congress.” In our view, the political economy of the United States skews toward private sector solutions to many issues, and a CBDC could potentially threaten many private enterprises in the financial system. We can envision a solution whereby Congress passes legislation that requires stablecoin issuers to become insured depository institutions with appropriate regulatory and supervisory oversight.

Under such a scenario, the line between stablecoin issuers and commercial banks would become increasingly blurred. But the advantage of such a scenario is that the private sector would continue to drive innovation in payment technologies. Moreover, this scenario would be more or less similar in design, and therefore familiar, to the current banking system. That is, the majority of the nation’s money supply is “private” money that is supplied by private enterprises. The only difference between the current system and the system of the future would be the form of money. Money at present is paper in form; it would be digital in the future.

Endnote

1 When we published our first report on January 10, there were about 16,400 digital currencies at that time. The number of digital currencies today exceeds 17,500. (Return)

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals