Inflation in the euro area again is heating up and data out on Wednesday (10:00 GMT) will probably underscore this trend. The harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP) is expected to have hit another record high in February, likely dashing hopes that inflation would begin to peak in the early part of 2022. But that’s not all. The war in Ukraine has exacerbated the energy crisis, meaning that soaring fuel prices could push inflation a lot higher over the coming months. Yet, the euro is sliding as the European Central Bank also has the economic costs of the Ukraine fallout to consider.

A short-lived hawkish tilt?

Before the geopolitical turmoil, the ECB was grudgingly plodding towards tighter policy, signalling to the markets that an early exit from quantitative easing was on the cards – a move that would also pave the way for an end of year rate hike. However, following the turn of events right on the EU’s doorstep, even the more hawkish voices within the ECB are having second thoughts about a speedy pull-out of stimulus policies.

Subsequently, investors have now started to scale back some of their previously aggressive rate hike bets, with the year-end market-implied rate being slashed by about 20 basis points. That, though, still suggests the ECB will raise its deposit rate by about 30 basis points by December, which shouldn’t be too surprising as the Eurozone’s inflation problem is unlikely to go away by itself.

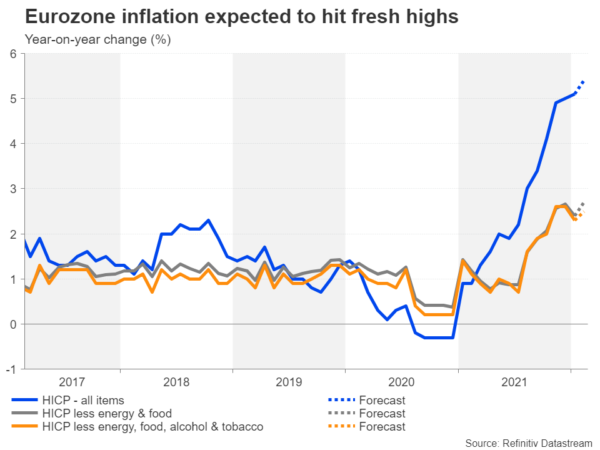

Eurozone inflation is still heading higher

The headline HICP rate is expected to have inched higher again in February, reaching a new all-time high of 5.4% year-on-year compared to 5.1% in January. More worryingly for policymakers, underlying measures have also risen to near record levels for the data series. HICP excluding food and energy is projected to reach 2.7% y/y, and the measure that additionally excludes alcohol and tobacco prices is forecast to edge up to 2.5%.

Avoiding a policy mistake

The ECB has so far stuck to its argument that most of the price pressures in the euro area stem from the surge in energy prices, which should fade over time, hence why it needs to be patient. But the crisis in Ukraine has complicated the policy path as the outlook has become even murkier than before. On the one hand, inflation is almost certain to peak much higher, on the other, growth is bound to take a hit.

The dilemma for the ECB is striking the right balance. If policymakers do too little too late to stifle inflation, there would be a greater risk of second-round effects where higher prices become embedded in the economy. If they overreact as President Christine Lagarde has repeatedly warned, they could end up choking the recovery.

Is the euro selloff justified?

Markets already appear to have made up their minds, however, pushing the euro sharply lower as the conflict in Ukraine unfolded. The single currency plummeted to a near 21-month low of $1.1105 in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion. It has since rebounded to above the $1.12 level, but unless it can climb back above the 61.8% Fibonacci retracement of the March 2020-January 2021 uptrend at $1.1290, the positive momentum could easily dwindle, opening the way for a retest of the $1.1105 low, followed by the 78.6% Fibonacci of $1.1002.

If, though, tensions between Ukraine and Russia de-escalate soon, for example, by agreeing to a ceasefire, the ECB might just be able to proceed with a reduced timeline of policy normalization come the March meeting, propelling the euro higher. In such a scenario, the bulls could target the 50% Fibonacci of $1.1492, which is close to the double top created in January and February.

The main danger for traders is that even if the ECB does turn more dovish in March, they may be underestimating the extent of the hawkish shift that was underway prior to the Ukraine war, in which case, a significantly pared back normalization plan might not seem so pared back in comparison to their own expectations.

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals