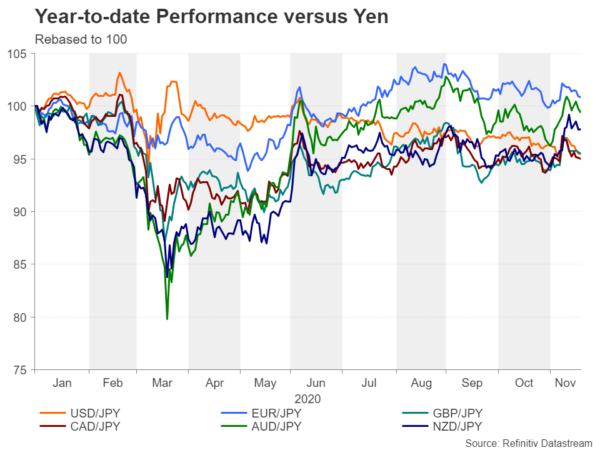

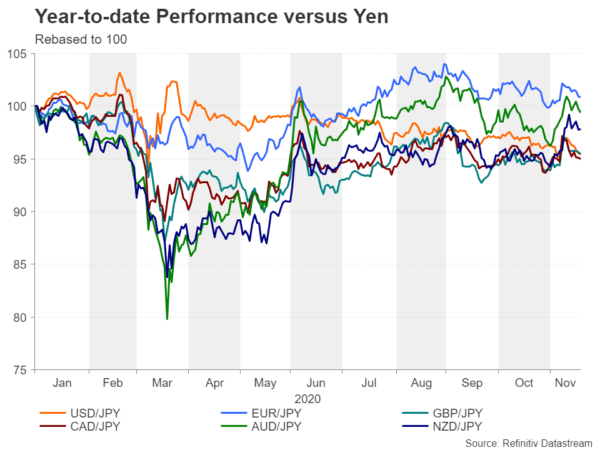

The Japanese yen has been on a steady downtrend against most of its major peers since March when it exploded higher during the virus-induced financial turmoil. Although only the euro and the Australian dollar have managed to erase their year-to-date losses, the gap for the remaining currencies isn’t too great. The pound is down about 3.5% and the Canadian dollar still needs to recoup around 4.5%. So the US dollar’s decline of a similar amount to the loonie shouldn’t come across as particularly unusual, until you start to consider that the dollar isn’t trending up. It’s trending down!

Battle of the safe havens

Usually during global crises or downturns, the dollar has typically appreciated against its peers at the onset of the market panic but fallen against the yen. When confidence begins to return to the marketplace, the greenback tends to fall as other currencies recover, except against the yen, whose own safe-haven status supersedes the dollar’s. The reason for that is what makes the two currencies an attractive destination for flights to safety in the first place.

The dollar is the world’s most liquid currency, hence, why it remains the number one reserve currency of choice and why investors rush to own it when there is a funding squeeze. But investors generally only flee to the dollar in huge numbers when there is a crisis on a global scale. At all other times, it is the yen that draws the most demand from regular bouts of geopolitical risks, such as political uncertainty, trade tensions and Brexit.

Japan is the world’s biggest creditor nation, so the assumption is that when fresh turmoil erupts, Japanese investors will offload their foreign assets – primarily government bonds – and convert them back into yen, pushing it higher.

USDJPY weakness defies rebound in risk appetite

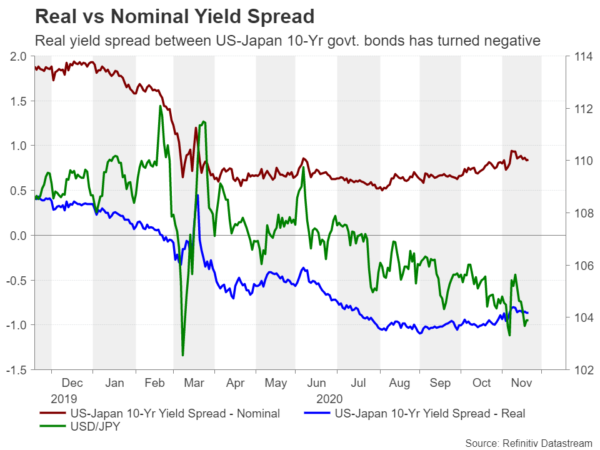

However, following the unprecedented volumes of stimulus injected by governments and central banks around the world since March, market stress has eased substantially and a global economic recovery is well underway. The United States can even boast its recovery to be stronger and more resilient. There’s also very little chance of the Federal Reserve cutting rates any lower, which means yield differentials are not expected to move in favour of the yen anytime soon. If anything, the spread on 10-year US-Japanese government bond yields has been rising since August, which should be supportive of dollar appreciation.

So why does the dollar keep falling against the yen? The missing piece in the jigsaw here is real yields. On an inflation-adjusted basis, yields in the US collapsed below Japanese ones after the Fed slashed its key lending rate to near zero back in March and they’ve remained below Japan’s ever since. But this doesn’t totally solve the puzzle because even on an inflation-adjusted basis, US yields have been edging higher in recent weeks. The end to the US election uncertainty and the discovery of a COVID-19 vaccine have spurred risk assets while hurting safe-haven bonds. Thus, the dollar should have made more of an attempt to break its downtrend versus the yen than just briefly spike higher in risk-on episodes.

Japanese yields no longer the lowest in the world

One possible factor that is likely keeping dollar/yen skewed to the downside is the dramatic decline in capital outflows from Japan. This is partly down to the narrowing yield differentials, not just with the US but with all other countries whose central banks had scope to cut rates during the pandemic. Japanese portfolio managers have significantly reduced their allocations to overseas assets this year as they are no longer as attractive. To make matters worse, the pandemic has additionally disrupted mergers & acquisitions, leading to an overall sharp decline in foreign outflows from Japan.

But the problems for dollar/yen do not end there. The soaring US fiscal deficit and expectations that the Fed will increase its asset purchases further, putting a cap on Treasury yields, make for a weaker dollar in the long run. Compounding this is the Fed’s recent revamp of its policy framework. The decision to target average inflation over time rather than a fixed goal is likely to drive real yields even lower as the Fed lets price growth run above 2%.

Virus risks have not dissipated

In the meantime, of course, the uncertainty from the coronavirus outbreak hasn’t entirely gone away. The stock market rally, fuelled by the abundance of liquidity, may give the impression that everything is almost back to normal, but it hides the ongoing pain for economies around the world, as a full recovery will likely not be possible until 2022 at the earliest.

And while the vaccine news is what everyone had been waiting for before mass distribution can begin, there is a cold dark winter to get through in Europe and America where virus cases are at record levels and deaths are rising alarmingly. In contrast, Japan is seen as a relative virus success story, as total Covid deaths in the country since the beginning of the outbreak remain below two thousand.

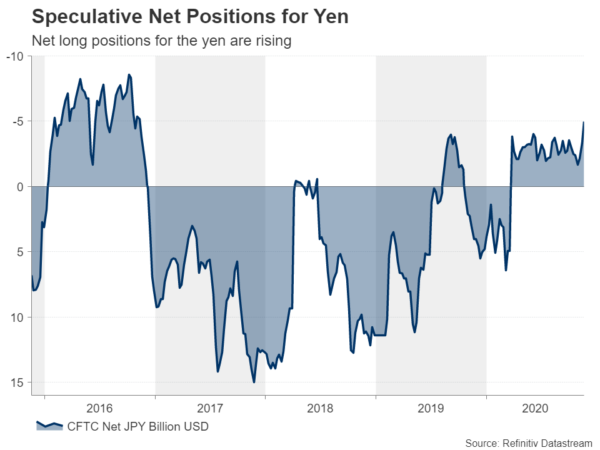

All these lingering risks can only imply investors still have plenty of reason to seek safety and are probably behind the recent increase in yen long positions (according to data from CFTC).

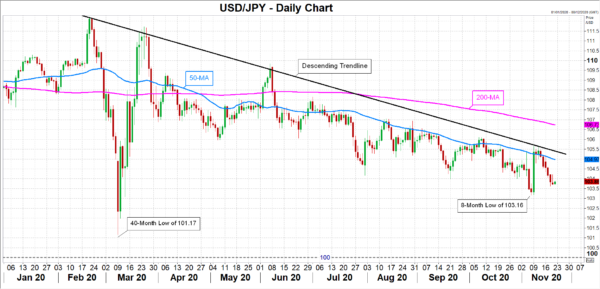

Bearish signals

From a technical perspective, dollar/yen is also looking increasingly bearish. The pair is trading below both its 50- and 200-day moving averages. More importantly, the fact that dollar/yen was unable to crack above its long-term descending trend line from the post-election and vaccine-led rallies signals that the greenback’s bullish days are probably well and truly over.

Although that may not necessarily mean the yen is set for similar gains versus its other major peers, Japan’s low inflation prospects and flat yield curve are now likely to work in favour of the currency than against it as was the case not that long ago.

The only caveat here is that Japanese policymakers are unlikely to let the yen appreciate beyond the 100 per dollar level. When the pair tumbled below 104 in the aftermath of the US election outcome, Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga didn’t hesitate to ramp up his rhetoric about the importance of stable exchange rates. Hence, any further moves lower could potentially see the 100-101 region become a heavily congested area like it did back in 2016.

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals