While 2019 was a turbulent year to be sure, every asset class still managed to end in the green, mainly thanks to central bank stimulus. In the FX space, the winners were the Canadian dollar and British pound, the US dollar was almost flat, while the euro underperformed. Looking into 2020, many risks still hang over the euro as the Eurozone is hardly growing, and while many strategists are calling for the dollar’s demise, that seems unlikely unless the Fed starts cutting again. The yen may have a cold start to the year but eventually recover, as Brexit risks resurface and US election uncertainty sets in.

Does ‘king dollar’ still reign?

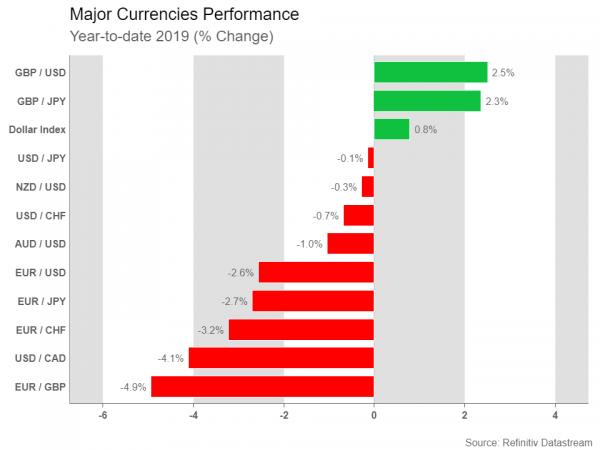

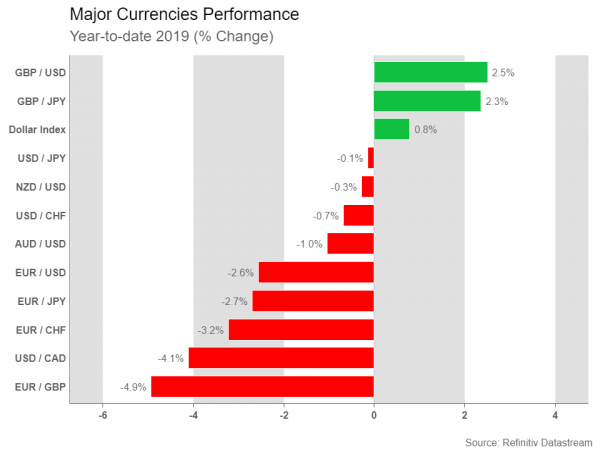

The world’s reserve currency is set to end the year – and the decade – on a high note. Yes, the dollar did surrender some ground to the British pound and Canadian dollar in 2019, but it was higher against many other peers, advancing by 2.6% against the euro for instance. This, despite a dramatic U-turn by the Fed, which abandoned its hiking cycle and instead cut interest rates three times to cushion America from the trade war and a slowing global economy.

Simply put, the US economy was an attractive destination for capital flows. Even accounting for the Fed cuts, America still offers much higher rates than most other G10 economies, a safe environment, and faster economic growth.

Now the question is whether this can continue in 2020. Crucially, many strategists are calling for losses, on expectations that the improved mood on trade will diminish the dollar’s haven appeal, a pick up in global growth will make the US less attractive by comparison, and uncertainty surrounding the presidential election will add a risk premium to the dollar.

While these are valid arguments, the real question is, where else can investors hide? Replicating the dollar’s high-yielding but safe-haven status is a difficult task. And for all its troubles, the US economy is still miles ahead of Europe – which is barely growing and is mired in structural and institutional problems. Low-yielding Japan is equally unattractive without a risk-off episode, while emerging markets seem particularly risky in an unstable trade environment.

Unless the Fed starts cutting rates aggressively and erodes the dollar’s rate advantage, or Germany announces a big fiscal spending package to boost the struggling euro area (see below), it’s difficult to envision any real downside in the greenback. Neither of those seems likely, over the coming months at least.

Euro waiting in the rain for fiscal stimulus – delays expected

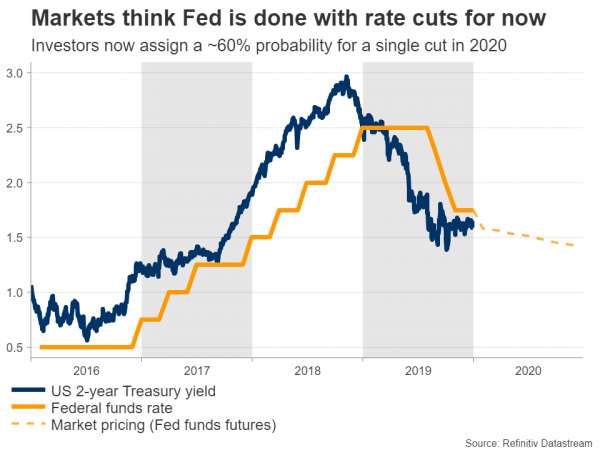

The euro area had a troublesome year, with growth slowing as Brexit uncertainties and trade risks brought the bloc’s manufacturing sector to its knees. The situation was dire enough for the European Central Bank (ECB) to relaunch its Quantitative Easing (QE) program only nine months after terminating it.

While growth now seems to be bottoming out, it is stabilizing at a very low level, so there isn’t much to celebrate. What’s more, European monetary policy is near its limits after years of heavy money printing, so more ECB stimulus – like bigger QE injections – will probably not do much to boost the economy. Rather, large fiscal stimulus is needed, but the only country with any real fiscal room is Germany, and Berlin has been painfully clear it has no intention of launching a major fiscal package.

Without such a spending package, growth is likely to stay anemic. Not to mention other risks, like the White House turning its sights to trade with Europe now that there’s a ceasefire with China. The top US trade official, Robert Lighthizer, recently said that America’s large trade deficit with the EU “can’t continue”, which may be a prelude of things to come.

And while investors have taken a more positive stance on Brexit lately, helping the euro recover, it may be just a matter of time until the threat of a no-deal exit comes back on the table (more below). All told, the euro will likely remain a funding currency in 2020, and persistent economic weakness could even see the ECB ramp up its QE dosage, which could keep the single currency on the back foot absent a serious fiscal package.

No end in sight to Brexit drama but BoE policy could also steer pound

After a tumultuous 2019, 2020 could be the year Brexit finally gets resolved. However, given that British PM Boris Johnson didn’t waste any time after his landslide election victory in setting a tight deadline of December 2020 to negotiate a post-Brexit trade deal, it’s not looking like next year will be smooth sailing for the pound.

Having won December’s snap vote on getting Brexit done, Johnson’s inflexible deadline should not have come as too much of a surprise. However, having just trimmed their short positions for the pound, this wasn’t what traders wanted to hear and Cable’s post-election rally quickly evaporated.

The most likely outcome is that the UK will leave the EU on January 1, 2021 with some sort of a temporary deal or Johnson will agree to a last-minute extension if enough progress is made. Yet, markets will not appreciate the uncertainty and the political posturing, meaning more bumpy rides for sterling ahead.

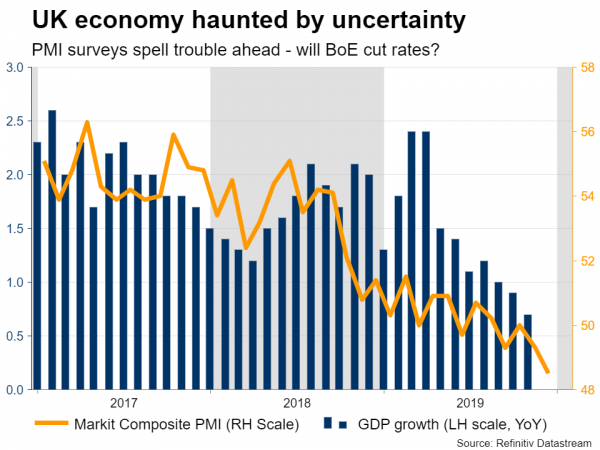

But perhaps a bigger source of uncertainty will be what the Bank of England will do. Policymakers are currently split as to whether the UK economy is slowing enough to warrant a rate cut and it could take several months before a clearer picture emerges.

A lot will depend on how much the end of the political deadlock boosts business spending and whether there’s a revival in Eurozone and global growth. Until investors can better gauge the UK’s growth momentum, and in turn the rate outlook, the pound will remain hostage to Brexit headlines. If the data continues to deteriorate and Johnson maintains a hardline approach, the pound could soon be revisiting the $1.25 level.

Yen: A hostage to risk appetite

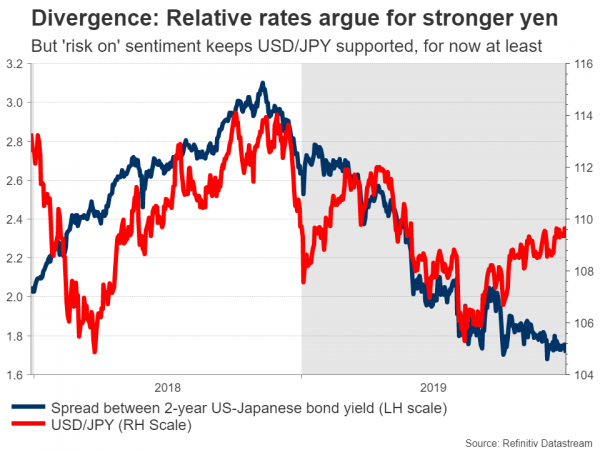

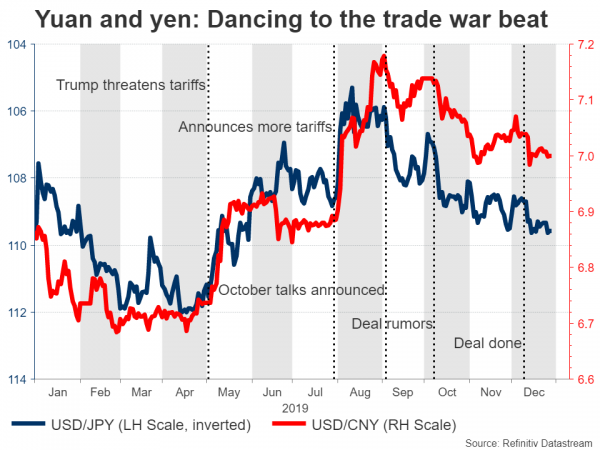

In Japan, the safe-haven yen had a volatile year, going from the worst performing major currency in early 2019, to the best performer as trade tensions escalated, and then back to flat against the dollar as the US and China reached a ceasefire.

2020 could shape out in a similar manner. The biggest risks facing global markets – trade and Brexit – have diminished substantially recently, hurting demand for the defensive currency. That positive sentiment could endure in the coming weeks, as the US and China sign their ‘phase one’ deal and the Brexit process finally enters its second stage, potentially setting the yen up for some early-year losses.

Looking further out however, the yen might come back. Even assuming the trade truce holds – and that’s a big assumption – the risk of a no-deal Brexit may still come back on the table. Unless the EU and UK can reach a full trade deal in eleven months, which is almost unfathomable given that the EU-Canada one took seven years to negotiate, the UK will need to extend the transition period. The problem is, PM Johnson has repeatedly vowed not to do so, so he might default back to threatening a no-deal exit to extract concessions as the deadline approaches.

Meanwhile, the lead up to the US presidential election could also see investors shun risky assets like stocks and turn to safe havens, especially if one of the progressive candidates – Sanders or Warren – secures the Democratic nomination. Both advocate higher business taxation to finance social programs, so it’s safe to say such a nomination would probably spook stocks, leading to a wider risk-off environment.

Yuan: With a mind on financial stability

China experienced a sharp slowdown in 2019, as the Trump tariffs and the associated uncertainty damaged the industrial sector and exports. The slowdown would have been even worse had Beijing not enacted proactive monetary and fiscal stimulus.

Looking into 2020, the risks for both growth and the yuan still seem tilted to the downside. The trade war has been put on ice, but there’s always a risk that it fires up again, especially if the White House feels Beijing isn’t living up to its promises or if Trump ramps up the ‘tough-on-China’ rhetoric ahead of the election. Meanwhile, the majority of tariffs remain in place.

Equally important, are financial stability risks. China’s total debt is already very high, as is its banking leverage, meaning the size of the banking sector relative to GDP. Therefore, adding more stimulus to boost growth is extremely risky, as it may compound vulnerabilities and amplify future shocks. Indeed, there are already some signs of stress, ranging from rural bank runs to defaults by state-owned enterprises. While these have been contained so far, this is certainly something to keep a close eye on.

Aussie, kiwi and loonie’s outlook still tied to trade war

The commodity-linked Australian, New Zealand and Canadian dollars had a rollercoaster 2019 as trade tensions got inflamed and defused time after time. While the loonie still managed to hold onto its gains from early in the year and the aussie and the kiwi bore the brunt of Trump’s trade outbursts, all three currencies look set to end the year on a positive note.

Australia’s, New Zealand’s and Canada’s dependency on exports has exposed their economies to the trade war. China is the biggest buyer of Australian and New Zealand exports, while the US is the largest market for Canadian producers. Hence, any disruption to those markets would have knock-on effects on the economies of Australia, New Zealand and Canada.

That’s already evident in Australia, where annual growth has fallen to the lowest since 2009 and even the once robust labour market has started to wobble. The Reserve Bank of Australia was quick to respond and cut the cash rate three times in 2019. Heading into 2020, investors think there’s an 85% probability the RBA will cut rates by another quarter point.

If the US-China ceasefire is preserved, those odds are likely to come down during the course of 2020, lifting the aussie. However, even against the backdrop of subsiding trade frictions there are still risks to the aussie’s uptrend. Inflation remains stubbornly low and without a pickup in jobs growth, which is essential for pushing up wages, the RBA is likely to ease policy next year, limiting the local dollar’s advances.

In contrast, the New Zealand dollar has more scope to extend its impressive rally from the 10-year lows brushed in October. Unlike the RBA, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand is not seen cutting rates further in 2020 as the economy appears to be stabilizing and a recently announced fiscal package should provide an additional boost.

Bucking the trend among G7 nations, the Canadian economy has proved the most resilient, even though growth in the country has not been exactly spectacular either. Still, the relative strength has kept the Bank of Canada (BoC) on hold throughout the year and markets don’t expect any change in interest rates during 2020.

The slightly bullish outlook for oil – Canada’s biggest export – for at least the early parts of 2020 should be positive for growth and a possible rebound in the US may further bolster the Canadian economy. However, it’s not an entirely rosy picture in Canada as the jobs market appears to be slowing and the BoC is keeping a close watch on consumption and housing amid some warning signs.

If the domestic economy remains solid and growth improves globally, the loonie’s outlook is positive as the BoC is more likely than the Fed to hike rates. However, in the event of a flare up in trade tensions, whether with China or the EU, the loonie could significantly underperform its peers as the BoC has more room to cut rates than its counterparts and markets currently don’t expect any easing.

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals