Summary

- The term “stagflation”, which was widely used in the 1970s and the early 1980s, essentially disappeared from the lexicon over the subsequent few decades. However, it has become in vogue again recently with the marked rise in inflation that is due, at least in part, to supply constraints.

- Stagnation can mean different things to different people. To some, it means an outright contraction in economic activity (i.e., recession). Even if “stagnation” is interpreted as an extended period of sluggish economic growth and elevated unemployment, we do not believe that the current economic environment meets this definition, as growth is anticipated to remain above trend.

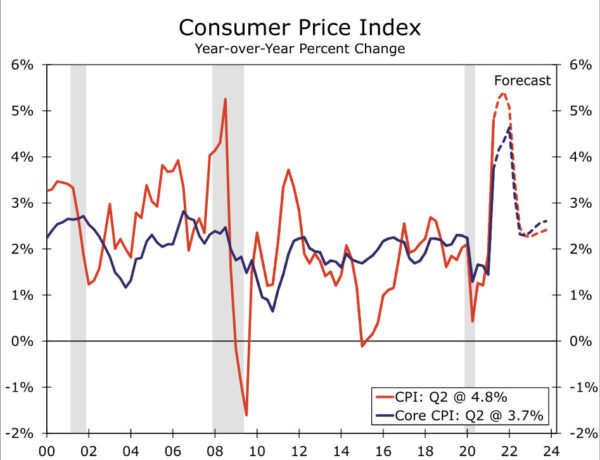

- Inflation has been pushed up recently by a combination of supply shocks and strong demand. But as businesses continue to adjust, the pandemic ebbs globally in the year ahead, and spending on goods shifts back toward services, we expect to see inflation recede.

- In contrast to the 1970s, labor demand remains exceptionally strong, so the unemployment rate should also recede in coming quarters.

- An upward spiral in wages, which would push prices higher as it did in the 1970s and 1980s, looks less likely today. Employee bargaining power is weaker today than in those decades due to a lower proportion of the workforce being unionized, and very few workers today having wages that are automatically indexed to prices.

- Although the rate of CPI inflation is likely to remain elevated in the near term and growth has slowed from the breakneck pace registered earlier this year, we do not believe that the U.S. economy is embarking on a period of stagflation.

Is It 1973 Again?

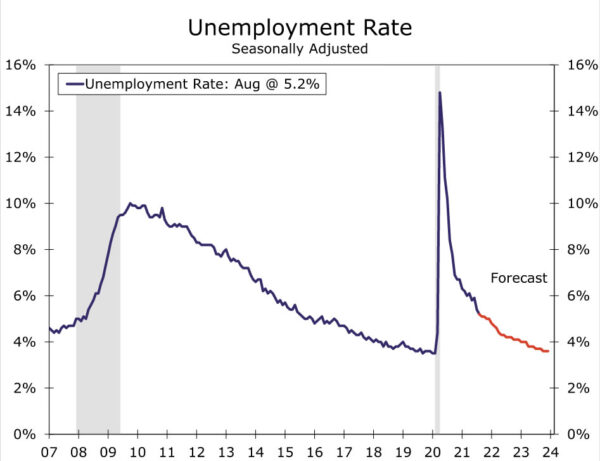

Not only has the COVID pandemic caused widespread human suffering worldwide, but it also has had profound economic consequences. The lockdown of the economy in the spring of 2020 caused the U.S. unemployment rate to spike to nearly 15%. At the same time, supply constraints have led to marked increases in the prices of many goods and services, pushing the CPI inflation rate in the United States up to more than 5%, the highest rate in roughly 13 years. A word, which essentially was forgotten during the past few decades, has re-entered the lexicon: stagflation.

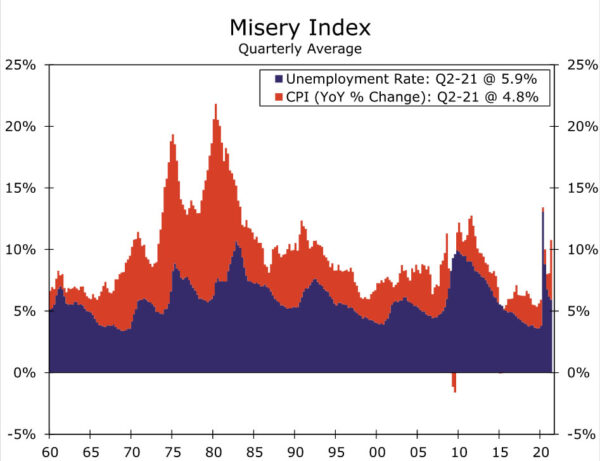

The term “stagflation” was coined during the 1970s to describe the economic backdrop of the times. The first part of the word is taken from “stagnation” while the second part comes from “inflation”, and it broadly refers to an environment in which inflation and unemployment are both high (or inflation is high while the economy is in recession or economic growth is sluggish). Another phrase that measured the extent of inflation and unemployment was coined during that time: the so-called “Misery Index”.1

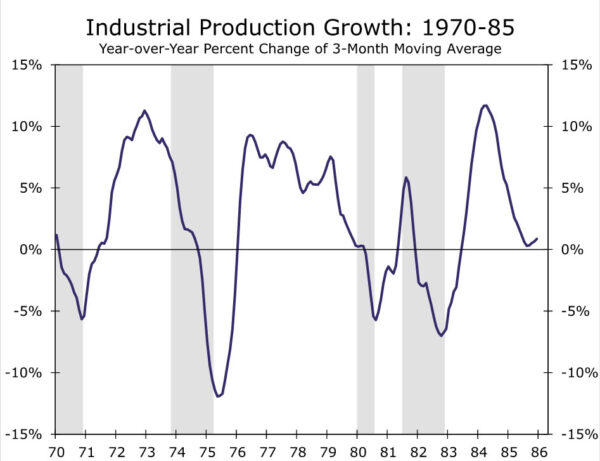

The Misery Index, which shows the combination of the year-over-year rate of CPI inflation and the unemployment rate, spiked to nearly 20% in the aftermath of the OPEC oil supply shock (Figure 1). The price of crude oil nearly trebled between late 1973 and early 1974, and the volume of oil imports, which shot up from less than four million barrels per day (bpd) in 1971 to more than six million bpd in 1973, declined modestly in 1974. The moonshot in oil prices and the plateauing in imported oil supply caused the industrial sector of the American economy to go into a tailspin (Figure 2). The unemployment rate shot up to a high of 9% in early 1975 while the CPI inflation rate surged into double-digit territory.

The Misery Index jumped even higher in early 1980 following the Iranian revolution in 1979. The price of crude oil more than doubled over the course of 1979, and industrial production contracted sharply again as oil imports declined. Labor costs continued to follow inflation, as roughly 60% of unionized workers were covered by cost of living adjustments (COLAs).2 The spike in interest rates that occurred in late 1979 and early 1980 added to the growth shock that hit the economy. The index receded as the economy exited the deep recession of 1981-82, and it generally remained in single-digit territory over the next few decades. It would rise into double digits occasionally, but never back to the heights of 1975 and 1980. The term “Misery Index”, which was used extensively in the 1970s and early 1980s, faded from the lexicon. But the pandemic caused the index to spike again in early 2020 as the unemployment rate approached 15%. Although the index has subsequently receded on balance, it remains in double-digit territory at present.

Supply Constraints Central to Any Period of “Stagflation”

Stagflation can mean different things to different people. Inflation is rather straightforward, but stagnation may be interpreted in different ways. Does the economy need to be in an outright recession in order for it to stagnate? If so, then the economy is not stagnating at present because the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) has determined that the pandemic-induced recession ended in April 2020. Or does stagnation simply mean that economic growth is subpar and/or the unemployment rate is elevated? However strictly one views the stagnation half of stagflation, a poor growth environment in combination with elevated inflation implies the economy is suffering from some sort of supply shock.

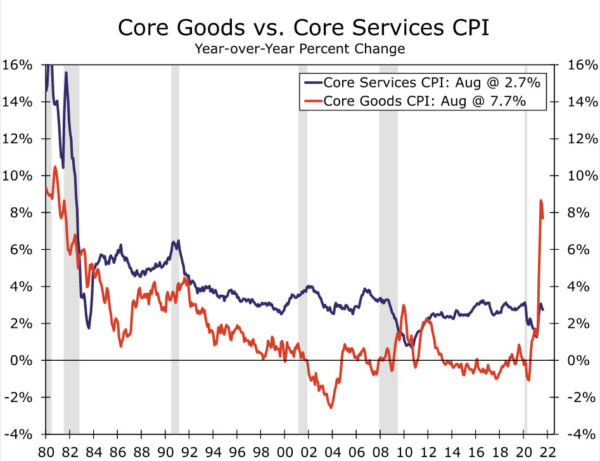

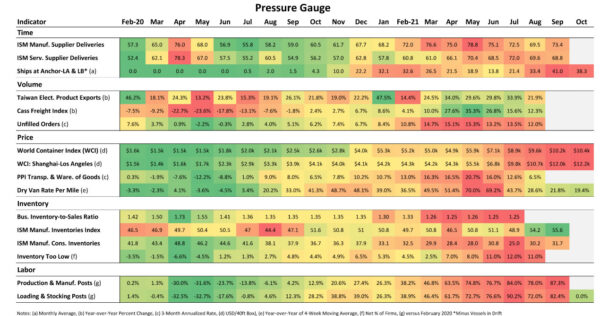

Elevated inflation at present stems in no small part from the bevy of supply shocks that have hit the tightly linked global economy since COVID. After the initial lockdowns in the early spring of 2020 that cratered production for a month or so, temporary factory shutdowns to contend with COVID outbreaks, parts shortages, fires, deep freezes and now insufficient energy have kept a wide range of businesses struggling to keep shipments flowing. Delicately choreographed supply chains have also struggled mightily, adding to the economy’s supply woes. As our Pressure Gauge shows, bottlenecks remain severe across supply chains. The number of ships awaiting anchor at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, together the country’s largest, hit a record high in September, while inventories remain exceptionally low (Figure 3). Consumer goods inflation, even excluding food and energy, has rocketed to a 40+year high as a result (Figure 4). The ongoing supply struggles for everything from food to autos should keep inflation elevated in the near term. However, as businesses continue to adjust, the pandemic ebbs globally in the year ahead, and spending on goods shifts back toward services, we expect to see CPI inflation recede back toward 2% by the end of 2022.

Inflation? Yes. Stagnation? No.

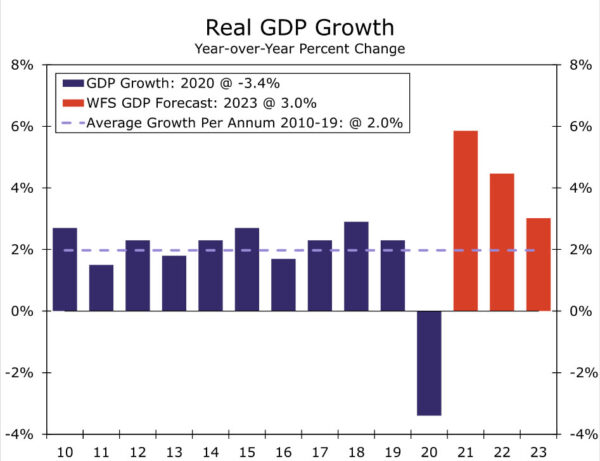

But the current bout of inflation is far from a pure supply shock. Inflation pressures have one foot firmly planted in strong demand. Output has roared back, eclipsing its pre-COVID peak in the second quarter of this year. The slowdown in real GDP growth relative to the first half of this year was inevitable with more distance put between one-time stimulus checks and the economy’s broad re-opening in the spring. However, the economy is far from stagnating. Household balance sheets remain unusually strong on the heels of a recession, with $2.3 trillion in excess savings still logged. Austerity seems to be the last thing on the minds of the Biden administration and congressional Democrats and, unlike the 2010s, state and local governments generally have strong budget positions that give them the wherewithal to spend. US corporations’ financial health also remains in solid shape thanks to soaring profits and low interest rates. We expect growth to remain above trend over the duration of our forecast horizon as a result (Figure 5). Growth may be slowing, but it is far from weak.

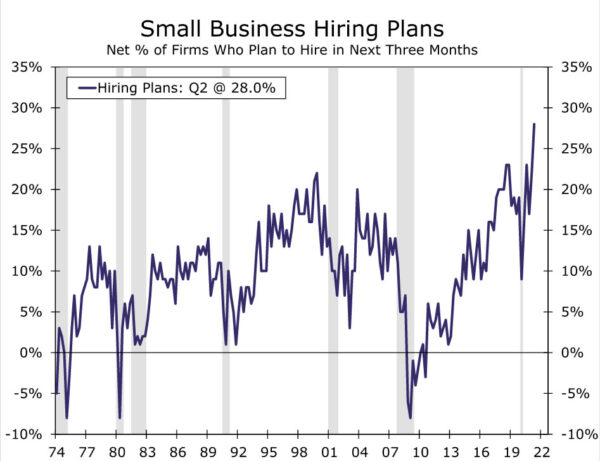

The prospects for the labor market are another important source of growth for the economy that marks a break from the 1970s. Labor demand remains exceptionally strong. A record share of businesses report that they are planning to hire, and the job opening rate is also at a record high (Figure 6). The lack of workers has been a major source of cost pressures in many industries, such as food services, in its own right. Yet an upward spiral in wages like the 1970s and 1980s looks less likely today. Employee bargaining power is weaker today, as only 6% of private-industry workers were unionized in 2020 compared with 17% in 1983 (the earliest year comparable data is available from the BLS). Unlike the 1970s, very few workers have wages that are automatically indexed to prices.

With hiring needs solid, employment growth is unlikely to go into reverse like in the mid- and late-1970s. We view the recent slowdown in hiring as more a function of constraints on the supply of labor, rather than faltering demand for workers that can incite the traditional recessionary dynamics of lower income, lower spending and even lower employment. With employers eager to hire, we expect the unemployment rate will continue to trend lower, albeit at a decreasing rate as the availability of labor should improve in the coming months.

We do not explicitly forecast the Misery Index, but combining our forecasts for inflation and the unemployment rate shows the index is likely to remain near double-digits in the next few quarters. While the unemployment rate is expected to gradually recede (Figure 7), we expect CPI inflation, measured on a year-ago basis, to remain above 5% through the early part of 2022 (Figure 8). However, with the initial burst of reopening related price hikes behind us and bottlenecks across supply chains expected to ease over the year, we expect the Misery Index to be back into the mid-single digits late next year. In short, we do not believe that the U.S. economy is embarking on a period of stagflation.

Endnotes

1The economist Arthur Okun first referred to the combination of inflation and the unemployment rate as the Economic Discomfort Index. The term “Misery Index” is attributed to Ronald Reagan.

2Devine, J. “Cost-of-living Clauses: Trends and Current Characteristics” Bureau of Labor Statistics. December 1996.

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals

Signal2forex.com - Best Forex robots and signals